PROVINCETOWN — A longtime haven for artisans and crafters looking for affordable spaces to create and sell their work is up for sale.

Whaler’s Wharf

ARTS BUSINESS

Film Society Looks to Future of Waters Edge

National anxiety about the fate of movie theaters strikes a chord here

The Waters Edge Cinema in Whalers Wharf is the only movie theater in Provincetown and, with Wellfleet Cinemas, one of only two on the Outer Cape. But the Waters Edge, like thousands of cinemas across the country, is reckoning with changes in the industry that threaten its sustainability.

Even as it has changed hands and names, the cinema on Commercial Street has been a year-round source of entertainment for most of the last century. Whalers Wharf was opened in 1919 as a 600-seat movie theater. In 1973, David Elmer turned most of the old theater into studio spaces and a craft market but maintained a small cinema on the second floor known simply as “The Movies.” The cinema was closed and converted to storage space in the 1980s.

In 1998, a catastrophic fire destroyed the old Whalers Wharf. The building was replaced with the current structure, including a second-floor theater that was named “New Art Cinema 3.” In April 2010, the theater was purchased by the Provincetown Film Society, the nonprofit that organizes the annual Provincetown International Film Festival, and given its current name after a 2012 renovation.

Last month about 30 people came to Waters Edge for the Film Society’s “town hall” — billed as a chance to hear from the community what programs, events, and types of screenings they would like to see in the future at the cinema. Sitting up front were the society’s Executive Director Anne Hubbell, treasurer Kevin Moss, and clerk Michael Colford. Hubbell explained that the society supports the cinema, adding, “Nobody’s getting rich off the movie theater business.”

Over the next hour and a half, Moss asked for reactions to possible programing at the theater, from first-run major studio films to short films to live sporting events and “theme nights.” Responses were mixed, but the consensus favored first-run major studio films and classic movies as well as community-centered events and showings.

Moss’s query about a possible redesign of the theater elicited a cacophony of complaints about the uncomfortableness of the chairs, the low quality of the sound system, and the theater’s inaccessibility. Lise Balk King, a local film professional, said later that people prefer not to come to Waters Edge “because it’s uncomfortable.” She believes a campaign to renovate the cinema would get community support.

After the gathering, Hubbell said that she had heard loud and clear the importance of creating a “comfortable place with great projection and sound.” She said the society is in the “hypothetical to early stages” of considering a possible renovation that would rely on a capital campaign seeking funds from individual donors and governmental grants.

“The cinema does not break even,” Hubbell responded to a question about finances. “We have to have donations and grants and community support.” Moss added that such an economic model “is very consistent with how nonprofit cinemas run across the country.”

Film Society officials would not provide figures for the cost of operating Waters Edge. Publicly available tax returns, however, show that in 2021 the Film Society had $910,000 in revenue and $734,000 in expenses. The cinema produced only $75,165 of that revenue, compared to $606,401 in government grants and individual contributions. Ticket sales in 2021 were down from $177,965 in 2019 and $203,076 in 2018.

Despite this decrease, Hubbell said there are no plans at present to close the cinema. Vanessa Downing, the managing director of the society, said that the town hall was not about telling the community that “we’re in a crisis” but rather that “we’re at a crossroads” with the shifting state of cinema broadly and the changing demographics and economics of Provincetown. The concern, said Downing, is less how to stay afloat and more how to ensure that the cinema remains “relevant and is meeting the mission of building community through film.”

Waters Edge is propped up by the Film Society. But the New York Times reported in September that, despite this summer’s double-blockbuster dubbed “Barbenheimer,” cinemas across America have been pushed to the brink by streaming and the pandemic. About 500 screens have gone dark since 2020, according to the National Association of Theater Owners.

Howard Karren, who is a member of the Film Society’s advisory board and curator of the Film Art Series at Waters Edge, said that the “whole ‘Barbenheimer’ thing distracted people from the fact that theatrical movies across the country are in a real downward slide.” Karren, who is the Independent’s film critic, says he thinks the society bought the cinema believing it would be a source of income but it “turned out to be something of an albatross” that has always lost money.

To Karren, the town hall was a step in the right direction because the future of local cinemas across the country requires dialogue with the community. Small towns, he said, are the most susceptible to cinema closures, and Provincetown will have to understand that the cinema is not a money-making venture and will need community support to exist.

Scott Sanders, the Emmy-, Grammy-, and Tony-winning producer and Provincetown resident, attended the town hall because he believes Provincetown needs to have a thriving cinema. “This community thrives on culture,” he said, “and it should have every piece of culture available to it.”

The Film Society intends to keep the doors of Waters Edge open through the winter. But it will take the community’s support to keep those doors open year after year.

THE SEARCH

The Art of Finding a Studio in a Shrinking Market

From the ashes of old Provincetown rise ideas for more workspaces

Years ago — before the 1998 fire that swallowed the Provincetown Theatre’s original structure, known then and now as Whaler’s Wharf — glassworker Christie Andresen lived in a different Provincetown.

“Nobody was considered a famous artist,” she remembers. “You spent a lot of time with artists without knowing they were artists because they were family people.

“I grew up in Whaler’s Wharf,” she continues. When she was a young teenager, a friend had a store there where she spent a lot of time. Jeweler Dale Elmer had purchased the building in 1973 with his partner, Buzz Buffington. Today, Andresen rents a studio on the second floor where she has been making and selling her stained-glass art for about nine years.

“Dale opened up Whaler’s Wharf to be a place where, as a craftsman, you could come in and rent a small space — but you had to make everything you sold,” says Andresen. “It was really a free-for-all for visual expression.”

Andresen says Elmer taught craftsmen who rented from him to “do it in full.” She recalls him saying, “Make a mess, make noise. Explain your process to customers, because they are not going to be able to find this anywhere else.”

“Working spaces for artists have been a priority at Whaler’s Wharf from the beginning,” says Ben deRuyter, now the managing partner of the Whaler’s Wharf building, which was rebuilt in 2000. “We strive to keep studio rents affordable. Rents on the second- and third-floor studio spaces have increased $210 per month during the 21 years that the building has been open.”

“Provincetown is a very artistic and entrepreneurial community. Always has been,” says Patrick Patrick, CEO of Shank Painter Associates, which owns Marine Specialties on Commercial Street and rents out 14 studios in a warehouse at 207 Route 6. “We have this great history of being a leading art colony, if not the leading art colony in the United States,” he says.

Maintaining a community of “individualistic, independent, creative-minded people, whether they’re artists, fishermen, or small business owners, is important in keeping Provincetown an interesting and unusual place,” Patrick adds.

“It’s as rare as hen’s teeth,” says artist Bill Evaul if you ask about inexpensive studio space on the Cape. Evaul has been renting a studio on Old Ann Page Way for 10 years. Affordable housing developer Ted Malone pioneered the project, which includes 18 dwellings and 10 studios. Malone’s Community Housing Resource Inc. completed construction in 2003.

Having a separate studio is important because many artists don’t have enough space to work in their homes. Small studios, however, also pose challenges. Evaul, for instance, keeps his printmaking press in a friend’s studio that is larger than his own. He also does large-scale paintings, a challenge in a cramped space.

Evaul says artists often find spaces through word of mouth — they go almost as quickly as news of a vacancy travels. “I’m always on the lookout,” he adds. “It’s just the most difficult thing in the world. You know, residential stuff is hard enough. Every little space that might have been a good studio has turned into a mini-apartment.”

Evaul wouldn’t say what he pays in rent for his studio but allowed that “it’s very expensive. For that much money you could get a really nice apartment in Ohio.”

In recent years, a few more reasonable spaces for artists have emerged. After securing a 99-year lease from the town in 2017, the Commons opened in 2019 at 46 Bradford St. at the site of the former Governor Bradford School. It has space for 10 artists to work on-site, and one additional space dedicated to the Generations Project, a New York City-based nonprofit working to compile oral histories of the LGBTQ community.

“Spaces go for $350 a month,” says Commons Executive Director Jill Stauffer, “but if someone can’t afford that, we will certainly have a conversation on what their budget will cover. We do subsidize artists.”

The Commons also limits renters to two renewals of their leases, which can be for three months, six months, or a year, “whatever period of time you need to get your body of work done,” says Stauffer. This renewal limit means that, even though the Commons is at capacity, people can still apply to rent space in the future. Currently, 11 are on the waiting list. “We wanted to give other people chances,” says Stauffer.

One thing that sets the Commons apart is its coworking program. Members pay $100 a month for access to a communal, 1,000-square-foot workspace with 19 stations and 10 additional seating spaces. There are also three meeting rooms, a phone booth, printer, and lounge.

According to Stauffer, “We’ve gotten some really great feedback from the artists on having the coworking people be in the space, because they’ll pop up and say hello, give feedback or a critique — or buy something.”

James Frederick Explores ‘Cape Cod Color’

Provincetown artist James Frederick will host a virtual opening on Frederick Studio Provincetown’s Facebook page on Friday, September 4th, at 7:00 p.m. The paintings in the exhibit, which express the light and color of the Outer Cape, are on view at Frederick Studio Provincetown at 237 Commercial St., Whaler’s Wharf, through September 13th.

GALLERY

Thinking Inside the Box

Peter McMahon’s designs turn simple materials into useful geometry

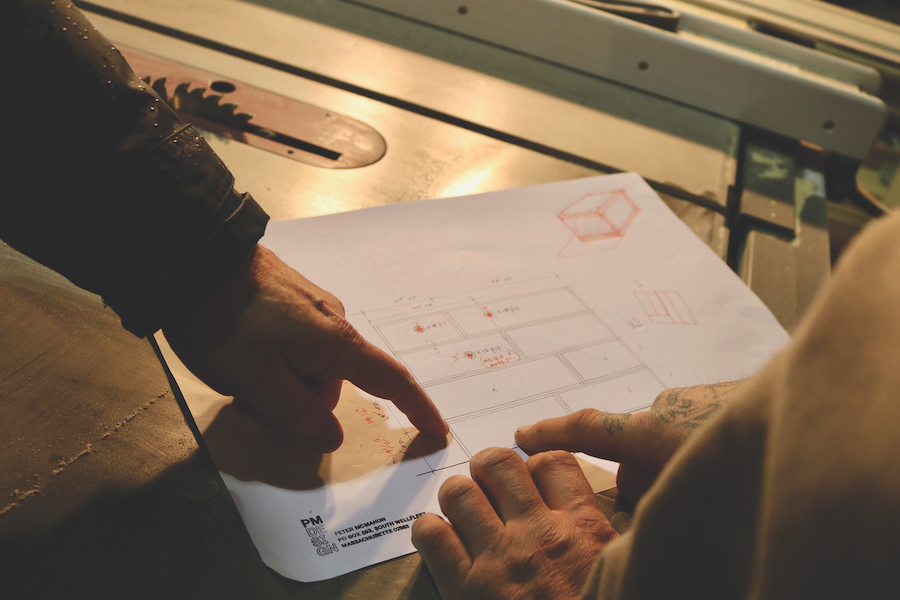

A few principles guided the planning for the Independent’s new office on the first floor of Provincetown’s Whaler’s Wharf: simplicity, versatility, and cost. The challenge was to create quiet work spaces within an open space big enough for staff meetings — without spending much.

Peter McMahon, the Wellfleet architect best known for creating the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, offered a solution in the form of modular boxes. McMahon confessed he is obsessed with boxes and their countless configurations. He admires their geometry and their utility.

“I have a definite idea about the best way to set them up for now, but they can be moved as you grow into the space,” McMahon said. An idea that suits a startup. —Molly Newman

“There is no problem that cannot be solved by a plywood box,” said McMahon. His vision turns a basic cube into the foundation for diverse uses: the boxes serve as shelves, room dividers, and support bases for desks. They can be easily rearranged and moved. Newspaper archives fit easily into their deep dimensions. When filled, the boxes provide effective sound absorption in an open office. (Photo Nancy Bloom)

Accessible design allows for an element of DIY: Independent staff and volunteers put the final touches on the cubes. The ¾-inch Baltic birch plywood requires only a light finish. Volunteer Eric Borg (left) and Harrison Fish, Independentadvertising associate, brush on the nontoxic, water-based polyurethane McMahon recommends. (Photo Nancy Bloom)

McMahon’s “Y” tables will be central in the office. “The workingman’s version” of a Jean Prouvé design, he says. The flying V shape of the steel legs is stable but never in the way. The tops are plywood finished in phenolic resin, which makes for a good work surface. (Photo Nancy Bloom)

McMahon’s main contractor, Paul Rosen, built the boxes in his large Eastham shop. The carpentry of gluing and screwing the pieces together is straightforward, but careful craftsmanship makes for more durable finished pieces. Left to right: McMahon, Rosen, and David Darakjy, who assisted in construction. (Photo Molly Newman)