ORLEANS — A pair of place-based education classes at Nauset Regional Middle School aim to help students gain a deeper understanding of their home by putting Indigenous knowledge at the center of the curriculum.

Place-based education strives to immerse students in local heritage and knowledge, but to teacher Susannah Remillard, that story should not begin with European colonization. The curriculum for her 7th-grade earth keepers class, developed with continuing input from the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe’s education department, uses Indigenous teachings and hands-on experiences to help connect students to the land.

“One of the goals is to give kids a broader understanding of where they’re from,” Remillard told the Independent. “They’re going to school at Nauset, so what does that mean? How do we honor the people who came before us?”

The Wampanoag people first came to Cape Cod more than 12,000 years ago and still live here today, Remillard said. Neither that lengthy precolonial past nor the life of Indigenous people in the present are usually emphasized in standard history courses.

“We need a new vision for place-based education, because we take it back 400 years, but we don’t go any further than that,” Remillard said. “The purpose of this course is in part to honor the pieces of the past that have been lost in so many curricula.”

All 7th-graders at Nauset Middle School take Remillard’s 10-week earth keepers class at some point in the school year. The “experiential education” course includes numerous hands-on activities, including cooking traditional Wampanoag foods and going outdoors to observe nature with greater attention and care.

“We’re trying to instill a way of seeing the land that’s different than this commodifying mindset that colonizers had to come with,” Remillard said. “We are all just one part of this interwoven system,” and every part is affected “when one part of that system breaks down,” she said.

The 7th-grade class lays the groundwork for Remillard’s 8th-grade change makers elective, which is also a 10-week course. In change makers, students are encouraged to become active stewards of the land, and they each develop and present a plan of action to help protect and honor the local environment.

Building a Wetu

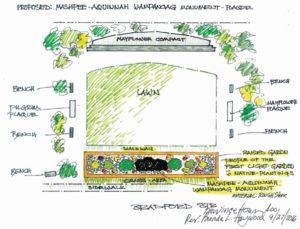

Remillard is also gathering grant funding to finance the construction of a wetu — a traditional Wampanoag house — to be built by Mashpee Wampanoag tribe cultural outreach coordinator Darius Coombs on school grounds this coming spring. The wetu will be surrounded by a teaching garden being grown by teacher Randall Burkert’s 6th-grade greenhouse class, which includes the Indigenous “Three Sisters” method of growing corn, beans, and squash together so that the plants nourish and support each other.

Because the wetu will be built on a section of school-owned land near Boland Pond that is open to the public after school hours, the plan is for community members to also have access to the structure.

“We don’t want it to be a museum piece,” Remillard said. “We want it to be a living part of our curriculum and our teaching.”

Coombs, who has built about 30 wetus, says he plans to begin the building process in the spring — first by marking the position of the 16-by-18-foot frame with pegs, then by harvesting the frames from local white cedar swamps. The next step, stripping bark to be layered over the frame, can happen only during a two- to three-month period in spring and early summer when sap is running through the tree.

“Sap separates the wood from the bark, so it’s sort of like peeling a banana,” Coombs said. “If you wait too long, the sap goes back down into the tree and seals to the wood again.”

Coombs and his crew will apply three or four layers of bark on the inside frame, then cover it with an exterior frame and a bark roof with a hole for rising smoke — even though, for safety reasons, this wetu will lack a traditional fire pit.

There will also be benches for students to use, Coombs said. The entire project is slated to be finished by late June.

The presence of traditional Wampanoag structures like wetus can often prompt non-natives to want to learn more about Wampanoag life, Coombs said. The history traditionally taught in schools often falsely confines Native Americans to the past, he said, while classes like earth keepers can help correct that narrative.

“People need to know where they’re at — people have to know the Indigenous people who live there,” Coombs said. “Not past-tense lived, but live. We’re still around.

“There’s so much history in those textbooks that puts us in the past,” Coombs continued. “We haven’t gone anywhere.”

The wetu-and-gardens project has already won a $6,000 grant from the Orleans Conservation Trust and a $5,000 grant from the town of Orleans. The total cost for the project is expected to be around $30,000.