Moisture, fog, the piney essence of forest and dunes — to commune with these in a Philip Malicoat landscape or seascape is to experience that certain slant of light when the grays and greens vibrate with inner life.

A selection of two dozen modest-sized Malicoat paintings are on view at the Schoolhouse Gallery. A few blocks west, at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, we are treated to 14 of Malicoat’s formal, seldom-exhibited studio paintings, spanning four decades.

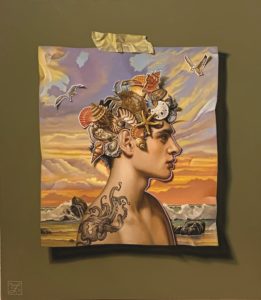

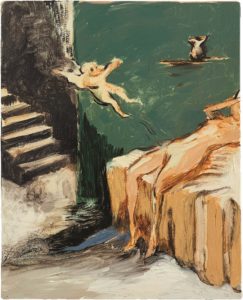

Rarely presented as a group, the studio paintings — those done in the artist’s personal workspace — are windows into Malicoat’s inner life, exploring his dreams and fantasies. They provide another dimension to the artist’s better-known scenic views and reveal his range. Among them are classically inspired paintings of his artist wife and a self-portrait that could hold its own alongside a Rembrandt.

Taken together, the paired exhibits offer a rare view of Philip Malicoat’s place in Outer Cape art history and in the scope of early 20th-century American painting.

The large-scale paintings reflect Malicoat’s studies with Charles Webster Hawthorne, founder of the Cape Cod School of Art, as well as his bond with friend and teacher Edwin Dickinson, who, almost a generation older than Malicoat, also studied with Hawthorne.

Malicoat was born in Indianapolis in 1908 and, after arriving in Provincetown in 1929, never left except for European travels. He was a member of the Beachcombers, a social club whose original roster is a who’s who of early Provincetown painters — Dickinson, Karl Knaths, Ross Moffett, Coulton and Frederick Waugh (no women were allowed — nor are they today). He often painted en plein air on the back shore, placing his easel not far from the family’s two-room dune shack.

Painter Robena Malicoat is one of Philip’s six granddaughters, the daughter of sculptor Conrad Malicoat and ceramicist and printmaker Anne Lord Malicoat. She speaks of her visceral reaction to her “Grandpa Phil’s” smaller oils, alive with spontaneity and movement.

Of a painting of pines in a snowy dunescape, Robena says, “It’s a really damp drizzly day, just kind of wet,” with a “silver-gray palette.” The paintings are beautiful without being beautiful, she says. “I wonder about them, not necessarily needing an answer.”

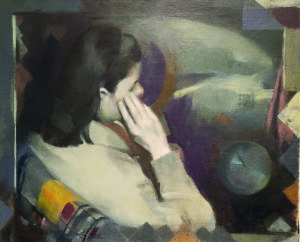

On a walk through the Schoolhouse Gallery to view the many paintings from the family collections, Robena describes Head of Sheila (1966) as “introspective.” Long fingers rest on her cheek as the auburn-haired beauty peers into a distant void in tones of gray. “Your attention is drawn to the hand,” Robena says. “You also imagine what she’s looking at, what she is thinking.”

Robena and her cousin, Breon Dunigan, also an artist, whose “trophy head” sculptures are shown at the Schoolhouse, are family historians and co-curators of the Malicoat exhibit at PAAM. Cataloging their grandfather’s work continues to be a long, exhilarating, and occasionally frustrating journey. From idea to fruition, the exhibit took them five years. Robena says the paintings are “contemplative, contained, and yet spacious.”

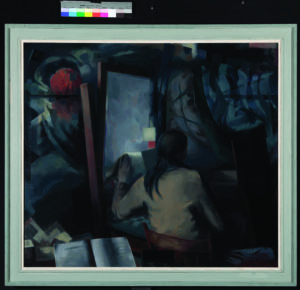

A large painting of Barbara Malicoat (1932), on view at PAAM (and the cover of the exhibition catalog), shows her pensively gazing into a mirror, a Renaissance-red cape draped over her shoulders. Malicoat often spoke of his preference for a limited palette, from which he would create a range of closely-related hues.

Breon, who has curated numerous exhibitions at PAAM and serves on the museum’s exhibition committee and board of trustees, appreciates Malicoat’s paintings of Ireland, Greece, and France.

She points out paintings of Athens in which grays mingle with violets, blues, and splashes of rosy peach. There are four from La Cadière, France. La Cadiere, Christmas Day (1960) is the most abstract — a gestural splash of blue-grays, its impasto surface pulsing with life.

These postcards from Phil’s travels also reflect the teachings of Charles Hawthorne, who followed the Impressionists in valuing the premier coup, the first strike, which translates as “don’t overpaint.” Breon remembers showing her grandfather drawings she made in art school. “Never spend more than a couple of hours on a drawing,” he advised. Phil’s paintings, she says, are intentionally done to capture that sort of energy, to capture the moment.

Malicoat also spoke of painting as an exercise in problem-solving. His Self-Portrait (1969) at PAAM offers insights: possibly he’s looking into a mirror. Geometric forms — a triangle, a vertical shaft — connect to a diagonal beam bisecting his shoulder; the edge of the artist’s nose parallels floating cubes.

A colorful blue jug extends into the foreground. Surrealism? Perhaps. “I recognize that vase,” Robena says. It’s one of many objects remaining in Malicoat’s studio, the rustic, inviting space where he painted most of his large-scale works, and where she now paints.

Malicoat’s loves of chess and music also appear in his studio paintings. In Reflection (1969), the model, seated at a chess table, stares into what Robena calls “indeterminate space.” Sheet music appears in the foreground. A swipe of rust-colored paint anchors a corner. A red cube rests on the model’s shoulder. “He is taking us on a journey into the process of painting,” Breon says.

Three Seasons (1965) spans 15 feet. The sensual triptych includes fragments of classical ruins. For the center section, Dunigan’s red-headed father, Phil, was a model. “He only posed for the head, and was lying down,” Breon says. His involvement took a couple of sittings — modest compared to what was usually expected of Malicoat’s studio models.

Mastering the act of painting itself, unlocking the mysteries of creating a dimensional entry point within the borders of a flat, two-dimensional surface, was Malicoat’s holy grail. In an interview in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, he speaks of the pleasures of the studio, his retreat and fortress. But the ocean gusts and solitude of the back shore were perhaps more primal sources of energy.

“He liked to paint waves,” Robena says. “And he loved to sail. A boy from Indiana, he came to Provincetown and discovered his calling.” Malicoat made four studio versions of Storm Over Sea (1967). White pulse marks punch their way across a furious gray sea: Malicoat has taken on the mantle of Ahab, the painter’s fierce brushwork chasing the white whale.

In an age of inflated artist reputations and greed-fueled prices, Malicoat remained the real thing — unpretentious, sociable, industrious, more interested in painting than in selling.

He was also open-minded about new styles. During the 1920s and 1930s, when PAAM had separate shows for “traditionalists” and “modernists,” Malicoat served on the exhibitions committee alongside Hans Hofmann, a modernist who had known Picasso and Matisse in Paris. Malicoat’s approach would have been considered more in line with the traditionists, but they became allies, agreeing to end meaningless distinctions.

For contemporary viewers, this slice of Provincetown history opens a door to revisiting Malicoat’s oeuvre through the lens of abstraction. Trained as a realist at the John Herron Art Institute in Indianapolis, Malicoat, who died in 1981, remained intent on capturing, in his own atmospheric style, recognizable figures and objects.

At the same time, his work is gestural — toothy and abstract. The much younger Helen Frankenthaler, who, during the 1950s, had one Provincetown studio in a private, wooded area and another facing the Bay, would have applauded Malicoat’s embrace of abstracted indeterminate space.

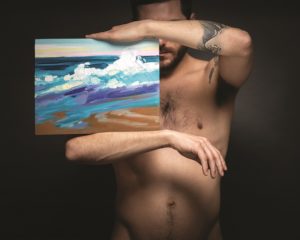

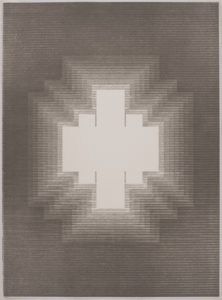

Vincent Amicosante, Harmon Gallery, Wellfleet: “I collect work from artists I know personally, admire, and support. I group pieces in small scenarios where they seem to work together by theme or style. One thing that is important to me is framing. I will re-frame some pieces so a grouping works better together. I have more work than I could possibly hang in my small space, so I rotate it. This is very refreshing and also helps preserve the artwork by avoiding constant exposure to sunlight.” (Photo Vincent Amicosante)

Vincent Amicosante, Harmon Gallery, Wellfleet: “I collect work from artists I know personally, admire, and support. I group pieces in small scenarios where they seem to work together by theme or style. One thing that is important to me is framing. I will re-frame some pieces so a grouping works better together. I have more work than I could possibly hang in my small space, so I rotate it. This is very refreshing and also helps preserve the artwork by avoiding constant exposure to sunlight.” (Photo Vincent Amicosante)