“The news ran like fire through the town. The sinking of the S-4 blotted out all other interests. There was no one who could think of anything else. It was as if we ourselves were imprisoned below decks with those men.”

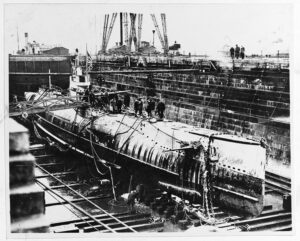

So wrote journalist, activist, and Provincetown resident Mary Heaton Vorse in her memoir Time and the Town. Vorse’s house faced out over Commercial Street onto Provincetown Harbor. There, in the cold and waning days of 1927, Vorse watched helplessly along with the rest of the townspeople as a noble rescue operation, thwarted by frigid weather and dangerous seas, worked overtime to save the 40 men inside the sunken submarine USS S-4.

On that Dec. 17, a Saturday, the S-4 had been conducting routine standardization tests along a submarine trial course marked by buoys near Wood End Light. Meanwhile, the U.S. Coast Guard destroyer Paulding was out on its regular patrol around Cape Cod Bay. It was the height of the Prohibition era, and the Paulding was checking for “rumrunners,” as Vorse called them.

It was 3:50 p.m. when the Boston Navy Yard received a radio alert from the Paulding: “rammed and sunk unknown submarine off Wood End, Provincetown.”

With neither vessel aware of the other’s presence in the area, the submarine was only 75 yards away from the Paulding’s port bow when the large destroyer sighted it surfacing, fast. The Paulding hooked a hard right and backed her engines, but it was too late. The submarine was punctured by the destroyer’s bow and sank immediately, according to reports of the U.S. Naval Institute.

People held out hope that disaster could be averted. Throughout the evening, Provincetown Coast Guard Boatswain Gracie traversed the harbor with a grappling hook trying to locate the submarine. As locals watched, Gracie connected with the wreck in the middle of the night but lost the line in the turbulent sea.

The next morning, with icy winds beating down on the harbor, rescue crews began arriving on the scene. Decorated naval officer Thomas Eadie was the first diver sent down from the rescue ship USS Falcon at 1:23 p.m. When he reached the wreckage of the submarine, Eadie was able to confirm that there were survivors on board: six men still alive and awaiting rescue based on the six slow taps he heard from inside the front torpedo room when he hammered on the hull to make contact.

There is more from Vorse’s account: “He went aft to the conning tower and he signaled. Only silence there. He went to the steel hatch over the engine room and signaled again. Again silence.” Less than 24 hours after the crash, the other 34 men aboard the submarine had already died.

The sinking and attempted salvage of the USS S-4 was national news, making the front page of the New York Times on Dec. 18, 1927. Weeks after the submarine sank, the Times reported what people in Provincetown already knew in “S-4’s Tragic Taps Revealed by Navy.”

Divers attempted to ferry oxygen to the trapped crew members and one civilian observer still alive on the sub. Working to install a descending line hose, they risked their own lives in the process. Fred Michels — the third diver at 7:49 p.m. and a friend of Eadie’s — became irrevocably “fouled” in the choppy, dark sea when his own air line was compromised during his mission to bring air to the S-4. Eadie rescued Michels just in time, according to David Robinson, the director of the Massachusetts Board of Underwater Archeological Resources and Thomas Eadie’s great-nephew.

The Falcon continued to communicate with the survivors through Morse code. The crew told the rescuers to “please hurry.”

The final messages relayed by the Navy were directed to 25-year-old Lieutenant Graham Fitch, one of the men in the torpedo room: “Your wife and mother are praying for you,” they said.

One final message from the S-4 crew came in at 6:20 a.m. on Tuesday: “I understand.”

Vessels came to Provincetown from every corner of the North Atlantic to help with the Navy’s increasingly desperate attempts to save the six men still alive on board, who had had an estimated 48 hours of oxygen when Eadie first dove down to the wreckage. Stormy seas kept dislodging the grappling hook that connected the efforts above to the submarine below.

“The town had become the center of the whole world,” Vorse wrote. Once the people of Provincetown learned that survivors were still alive inside the submarine, Vorse recalled, they became collectively frustrated with the Navy’s inability to perform the rescue, not understanding the challenges posed by the environmental conditions.

In a retrospective piece, the Provincetown Advocate editorialized in 1950, “Fishermen and their folk, eager to do all in their power to save the 40 men trapped in the submarine, railed at the inaction and stupidity of Washington.”

The air line was finally hooked to the S-4 torpedo compartment on Wednesday afternoon after the weather calmed, but it was too late.

To this day, 96 years after tragedy unfolded just off Wood End, an annual memorial service is held at St. Mary of the Harbor Episcopal Church for the 40 souls of the sunken submarine.

As Vorse wrote in 1940, “Provincetown never forgets the S-4.”