PLYMOUTH — The company decommissioning the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station in Plymouth has not said much about where the radioactive water it proposes to release into Cape Cod Bay would go.

Holtec International, which purchased the Pilgrim plant when it shut down in 2019 and is currently decommissioning it, has said some of the one million gallons of water from the spent fuel pool, reactor cavity, and other plant systems is still being used, so it’s too early to test it.

The lack of information has stalled any discussion of the effects of releasing the water into Cape Cod Bay. Legislators and activists are fighting to prevent the release from happening at all. But in case it does, scientists have been examining how the water pathways and ocean currents flow between the Plymouth shore and Cape Cod Bay.

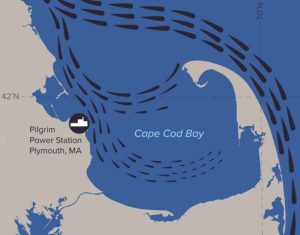

Irina Rypina, a physical oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), is an expert in ocean currents. To determine the currents in Cape Cod Bay, Rypina used data collected from drifter buoys over more than a decade. The drifters are designed to closely follow ocean currents, Rypina said.

The results are clear.

“All the different techniques that we tried on this drifter dataset point to the same general conclusion,” she said. “Part of the water originating from the Pilgrim power plant is likely to flow into the bay and another part is likely to head towards Race Point and its nearby beaches on the Outer Cape.”

As shown in the illustration on this page provided by WHOI’s graphics department, the current splits into two branches. The first branch moves east towards Provincetown, hugs Race Point, speeds up, and then flows southward along the ocean side of the Outer Cape. The second branch moves south into the bay and slows down. While the water headed for Race Point would arrive there in three to five days, the slower current would result in the released water reaching the eastern part of the bay in 6 to 12 days. The illustration shows mean, or time-averaged, circulation.

“The tides and other transient currents get filtered out when we take the long-term mean,” Rypina said. “The timing of the release is likely to be important. Tides, winds, and seasonal variability are all important players and can cause a reversal of the flow.”

But those varying factors are temporary.

“The reversal may initially send the release north toward Duxbury, but it eventually turns and heads south to the bay or east toward Race Point,” she said.

Other scientists have drawn up probability maps, using models that incorporates factors such as wind-driven currents and tides. Their conclusions were essentially the same as those drawn from the drifter data.

Rypina has been involved in studying the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear disaster that occurred in Japan in 2011.

“We were one of the first groups to measure concentrations of radionuclides in the ocean waters offshore of Fukushima,” she said. “Since then, we have done a number of large-scale surveys to monitor concentrations of radionuclides throughout the Pacific Ocean. Even after 10 years, we are still seeing small concentrations of Fukushima-derived radionuclides in the ocean waters in the Pacific.”

She said more research on Pilgrim’s proposed release of water is needed to understand what might wash up onto the beaches or linger in the sediment. “I think we need more information about the content of the wastewater,” she said. “For example, the types of radionuclides and the concentration of radionuclides.”

Ken Buesseler, a radio-chemist at WHOI, studies the distribution and fate of radioactive elements in the ocean. His experience includes assessments of releases from Fukushima and Chernobyl, and those related to the decades-old nuclear bomb testing in the Marshall Islands.

In a recent email discussing the possible release of radioactive water from Pilgrim, Buesseler remarked on the lack of details. “Until we have an accounting of what different radioactive elements will be released and their concentrations, the impact of one million gallons is impossible to evaluate,” Buesseler said.

The information should not simply be a statement that concentrations “will be below some allowed threshold but actual values for the stored water today, by isotope, detection limit, volume.”

Buesseler went on to say that radioactive contaminants have vastly different fates in the ocean depending on their chemical nature. “Some dilute and mix and are transported the same as the water, like tritium,” he said. “Others are more likely to be associated with marine sediments, like cobalt-60, and others accumulate in marine biota. Usually cesium isotopes and strontium-90 are of concern.”

Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station permanently shut down in May 2019 and was purchased by Holtec International, the private company now decommissioning it. After a plan to consider release of the radioactive water from Pilgrim’s spent fuel pool, reactor cavity, and other systems into the bay caused a public outcry, Holtec announced it had put the decision on hold for 2022.

Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station permanently shut down in May 2019 and was purchased by Holtec International, the private company now decommissioning it. After a plan to consider release of the radioactive water from Pilgrim’s spent fuel pool, reactor cavity, and other systems into the bay caused a public outcry, Holtec announced it had put the decision on hold for 2022.