Testing for the presence of PFAS — compounds linked to a broad array of harmful health effects — is set to begin in Wellfleet and Truro. The testing is part of a program being offered by the state’s Dept. of Environmental Protection (DEP). Massachusetts began to regulate PFAS only last fall.

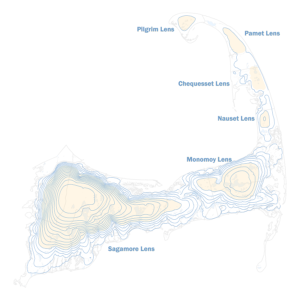

The DEP program focuses on 84 communities where more than 60 percent of residents are served by private wells. That’s because PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) have been found to seep into soils, groundwater, and surface water.

Known as “forever chemicals” because they never completely degrade, these compounds are manmade and date back to the 1950s. They are present in some of the foams firefighters use to put out flammable liquid fires, in nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting, and many other everyday items.

According to the DEP website, studies indicate that sufficiently elevated levels of PFAS have harmful effects on fetuses and infants, the thyroid, liver, kidneys, certain hormones, and the immune system. Some studies also link PFAS to cancer.

Well water tests have already been completed in about half the participating towns across the state. With 420 private well results in, so far 95 percent are below the standard the state has set for public drinking water — that is 20 parts per trillion of the six forms of PFAS the DEP is focusing on — according to Edmund Coletta, the DEP’s director of public affairs.

PFAS have been found in towns on the Upper Cape that border Joint Base Cape Cod, and in Hyannis, because of the firefighter training academy there.

Provincetown has tested its municipal water supply twice for PFAS, in April and July. Water Supt. Cody Salisbury said there was no presence detected. “We haven’t seen anything to indicate we have any issues,” Salisbury said.

Eastham posted on its website that testing done in April did not detect PFAS in that town’s municipal water system. Because Wellfleet and Truro have expanded populations in the summer, the state suggested waiting until now to do the tests.

While the Outer Cape’s broad swaths of protected land make the discovery of PFAS here seem improbable, Coletta said likely sources of contamination could include historic dumping areas, airports, and fire stations where training with firefighting foam was done.

Wellfleet has a former landfill on Coles Neck Road, south of the Truro-Wellfleet town line and west of National Seashore land. Truro has a closed landfill on Route 6, according to the DEP. Both landfills have been capped, but neither is lined, which creates the possibility of contaminants leaching into groundwater.

The Silent Spring Institute, an environmental organization that has extensively researched the compounds, found as early as 2011 a correlation between wells with higher levels of nitrates and wells with PFAS, said Laurel Schaider, a senior scientist with Silent Spring.

Phil Brown, a professor of sociology and health sciences at Northeastern University and the director of its Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute, said Silent Spring’s findings suggest that private septic systems could be a source, too. “Because there are so many consumer and food products with PFAS, every household can yield them in the waste stream,” Brown wrote in an email. He lives part-time in Wellfleet.

The newly available testing in Wellfleet and Truro will be limited to 40 private well owners from each town. Those interested in participating must apply. The sign-up link for testing is at dwp-pfas.madwpdep.org.

Selection will be on a modified first-come, first-served basis, within priorities including geographic distribution throughout the town and proximity to potential PFAS sources, according to the DEP website.

In Truro, the state agency is looking to do at least some sampling in the area of the former Air Force Station in North Truro, according to Emily Beebe, the town’s health and conservation agent. The station did radar surveillance and closed in 1994. The land was transferred to the National Park Service. DEP is also looking to sample near the former landfill.

Wellfleet didn’t make the initial list of communities last fall, according to Hillary Greenberg-Lemos, the town’s health and conservation agent. “We petitioned to be part of it,” she said. “Now our job is to get the word out.” The town has the information posted under “news” on its website.

Those selected will be sent a free sampling kit and will collect the samples themselves. The method used will test for all 18 PFAS compounds, including the six (referred to as PFAS6) that Massachusetts is regulating.

Under Massachusetts drinking water standards, the sum of PFAS6 compounds may not exceed 20 parts per trillion. To date, there are no enforceable federal standards, although the federal Environmental Protection Agency has an advisory standard of 70 parts per trillion.

Private wells whose initial samples exceed 10 parts per trillion will be asked for a second sample to confirm the results.

If a private well tests above the limit, the state will provide technical assistance on ways to reduce exposure, including the use of bottled water and installation of treatment systems. The cost of those measures will be borne by the home owner unless the source is found to be off-property.

The 12 additional PFAS compounds that remain unregulated at this point will also be analyzed by the certified laboratory and results for all 18 PFAS compounds will be reported.

While many of the additional PFAS included in the tests are believed to pose less of a health risk, according to the DEP website, it also states, “it is important to monitor these other PFAS in order to help target future research and regulatory efforts.”