Editor’s note: After this week’s Independent went to press, Mass. Attorney General Maura Healey’s office issued a statement about the release of radioactive water into Cape Cod Bay. The report below has been updated to include that late-breaking development.

PLYMOUTH — No one knows yet which radionuclides and other contaminants are in the million gallons of radioactive water that Holtec International has proposed dumping into Cape Cod Bay in decommissioning the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station.

That lack of knowledge seemed to make it impossible for state and federal health and water quality agencies to say what authority they might have to prevent the release.

But on Wednesday, Feb. 2 at 4 p.m., a statement from state Attorney General Maura Healey’s office said release of the water was prohibited.

“The facility’s permits prohibit the discharge of spent fuel pool water and wastewater generated by the decommissioning process into Cape Cod Bay and we expect Holtec to abide by those rules,” said Chloe Gotsis on behalf of Healey. “Our office will continue to coordinate with state agencies to ensure that public health, safety, and the environment are protected during ongoing activities at Pilgrim.”

Before Gotsis’s statement, discussion of who would have authority over the proposed dumping focused on potential contaminants other than radioactivity in the water. The water has not yet been tested because some of it is still being used as “shielding.” Highly radioactive reactor components are kept under water while they are being segmented and put into containers to protect workers.

More than 100 people tuned in to a remote Jan. 31 meeting of the Nuclear Decommissioning Citizens Advisory Panel (NDCAP). Most were hoping for some assurance that there would be no release of radioactive water into the bay.

There was no such assurance at the meeting.

The NDCAP comprises representatives of state agencies, local officials, and a handful of citizens. Its job is to help oversee decommissioning: keeping the public informed and offering advice on how the job should be done.

The panel learned at its last meeting in November that Holtec International, which owns and is decommissioning Pilgrim, was considering a few options for getting rid of 1 million gallons of radioactive water from the spent fuel pool, the reactor cavity, and other plant systems.

Releasing the water into Cape Cod Bay in batches of 20,000 gallons is one option. Others include evaporation — where it goes up into the clouds and comes back down in the rain — and trucking it offsite to a disposal facility.

When news of the potential dumping became public, protests led Holtec to pledge not to release any of the water into the bay in 2022.

The fishing community has been vocal in its opposition.

“The livelihood of so many, providing nourishment to so many more, might forever be lost,” said Mark Cristoforo, executive director of the Mass. Seafood Collaborative, during a “speak out” event before the NDCAP meeting. Fishermen’s livelihoods would be “sacrificed on the altars of greed,” he said.

State Sen. Susan Moran, a Falmouth Democrat who is leading a legislative effort to block the dumping, said legislators had met with state officials to discuss what could be done. They plan to meet again in March.

The state attorney general and Holtec signed an agreement in 2020 with a long list of requirements. But it’s not clear whether the agreement gives the state authority to regulate the release of the water.

Legislators have also filed emergency bills in both the state House and Senate to prohibit the discharge of radioactive material into coastal or inland waters. Violators would face “steep fines,” Moran said.

“We will never allow the dumping of radioactive material in Cape Cod Bay,” she said.

Jack Priest, director of the radiation control program for the Dept. of Public Health and an NDCAP member, expressed frustration over the lack of information.

“It would be useful to have more facts,” he said. “We haven’t even seen what’s in the water. Are there other contaminants?”

The state’s water discharge permit for the nuclear plant, called the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, regulates an array of contaminants. The state Dept. of Environmental Protection and federal EPA can stop the release of the water into the bay if it contains contamination levels that exceed those allowed in the permit. But the permit does not regulate radioactive contamination, which is under the authority of the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).

Priest also complained that Holtec seems to have dismissed the option of trucking the water to a disposal location.

“If you’re evaporating the water filtered from the stack, it eventually makes its way to the ground wherever the cloud floats to,” he said. “Or you’re doing a liquid dump into the bay. Both are lousy choices.”

David Noyes, senior compliance manager for a Holtec affiliate, assured Priest that trucking remains on the table.

But it’s been made clear by Holtec Decommissioning International’s president Kelly Trice that the company strongly favors discharging the water into the bay.

In a public statement last week, Trice cited the potential for accident inherent in trucking the water to a disposal facility. Evaporation, he said, would require large quantities of electricity and possibly the use of a diesel generator to produce heat. While hundreds of thousands of gallons of effluent have been evaporated over the last couple of years, the heat source was the pool where the spent fuel assemblies from nearly five decades of operation were stored. That fuel has been moved into massive steel and concrete casks.

Mary Lampert, an NDCAP member and director of an activist group called Pilgrim Watch, questioned Holtec’s safety concerns related to trucking. “Holtec wishes to have an interim waste storage site and have spent fuel trucked from all over the country, and they have no problem with transportation,” she said. Holtec expects to have a license for its planned storage facility in New Mexico approved by the NRC sometime this month.

Lampert tried to have NDCAP resume a monthly meeting schedule rather than every two months, but she failed to get her motion seconded. The next meeting will be at the end of March.

The NRC is scheduled to attend that meeting. NDCAP co-chair Pine duBois said a representative from the EPA would also attend. Lampert said Seth Schofield, senior appellate counsel for the attorney general, should be invited. Schofield was instrumental in hammering out the settlement agreement with Holtec. Lampert said Schofield could clarify “what specific authority the state has.”

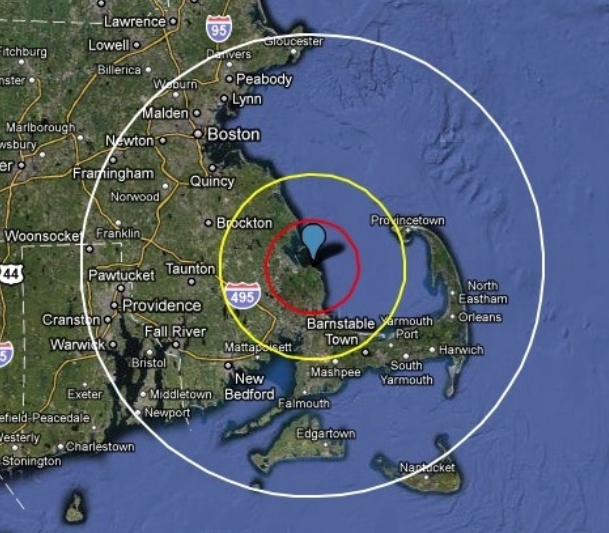

Another panel member suggested asking a scientist from Woods Hole to attend, citing comments senior scientist and oceanographer Irina Rypina made in the Independent last week. Rypina said that contaminated water would be trapped in the bay rather than filtering quickly into the ocean because the shape of the land creates a semi-enclosed space. “A tracer released into Cape Cod Bay would recirculate and stay in the waters within the bay for a long time,” Rypina said. “And then will likely end up in the sediment on the ocean floor or on the beaches inside the bay.” The same thing would happen to the radionuclides in the water released from Pilgrim, she said.