Dan Sanders visits Ballston Beach most days, looking out on the vast stretch of ocean where so many ships, overwhelmed by nor’easters or shattered on shoals, lie with their ill-fated crews beneath the waves.

According to the Cape Cod National Seashore, more than 3,000 shipwrecks have occurred over the last 300 years along the perilous stretch of coast running from Chatham to Provincetown.

Born in 1936, Sanders’s interest in ships and shipwrecks dates to his early years in Sandwich, where he and his mother stayed at his grandfather’s house while his father was abroad working as a war correspondent.

“My grandfather used to bring me to the shipwrecks when I was a little boy,” Sanders says. By the time he was nine, he was already fashioning models of the ships that figured in his grandfather’s stories. “I made them from the wood stacked behind the house,” he says. “When my grandfather saw them, he bought me some paint.”

One of his first projects was prompted by a report of a German U-boat in Cape Cod Bay during World War II, news that filled him with excitement. “I went out of my mind and made a model of the submarine,” Sanders says. It was a good enough replica that “a grownup bought it from me for five bucks,” he adds.

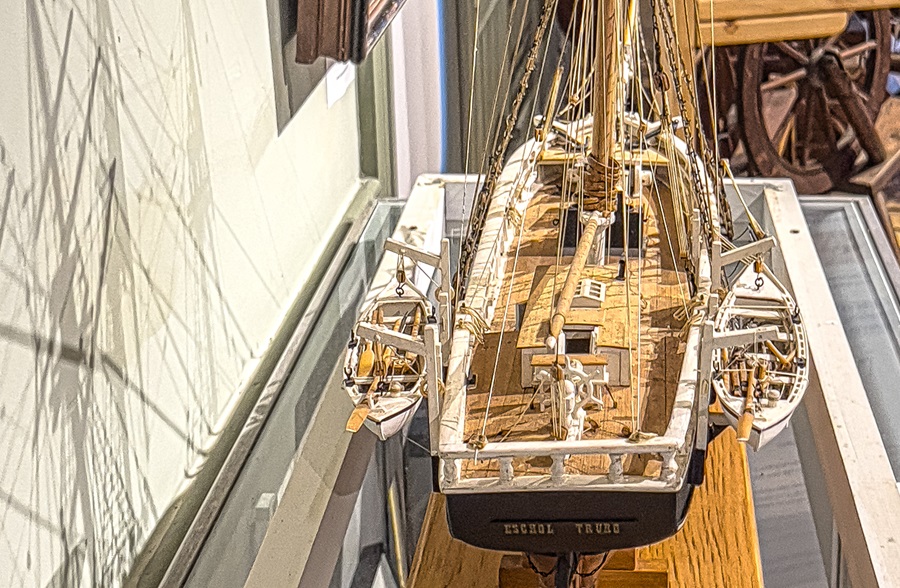

Sanders went on to fashion many scale models of ships that met with disaster, as well as of some that met kinder fates, and his work can be seen at the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History, the Mystic Seaport Museum, and the Connecticut State Library. But most of his models are on permanent display at the Highland House Museum in Truro, where Sanders provides presentations on the originals’ histories each summer.

Sanders struggled at school, he says, and he remembers his grandfather telling him, “You just learn differently.” Building models, he says, was a way “to concentrate my thinking.”

Sometimes his curiosity coupled with his tinkering skills got him into trouble. When he was 12, Sanders recalls, he fashioned a diving helmet out of an old bucket, using a discarded porthole for a faceplate. He then persuaded a couple of pals to man a hand pump on the deck of his boat to provide him with air through a hose as he dove about 20 feet down to explore a sunken rum runner.

“I was bumping around with the kids above pumping like hell,” he says. Then his makeshift helmet got stuck in the wreck and, helmetless, he surfaced too quickly and got the bends. That experiment ended in an ambulance ride, but it prompted his parents to provide him with proper scuba gear.

His different way of learning didn’t prove to be an obstacle for long. Sanders was accepted at both Harvard and Tufts, thanks, he says, to an award-winning science project he submitted to a national competition. For that, he looked into why broken hips are common in humans and, using a polariscope, placed the blame on what he saw as the precariously placed trochanter of the femur bone. His project included some mounted skeletons of animals he’d found as roadkill and boiled, as well as a model he carved himself.

Sanders chose Tufts. He graduated with a degree in physics and went on to earn a doctorate there. His studies led him to a career as a physicist at Pratt & Whitney in Connecticut.

“You hear the saying ‘It doesn’t take a rocket scientist,’ ” he says, laughing. “Well, I’m the rocket scientist.”

The company had a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration for the Apollo missions, and Sanders helped design a mission-critical fuel cell that produced onboard electric power. One perk was being present for the launches.

Sanders worked his own schedule at Pratt & Whitney, usually completing a full week’s work in four days. “I’d get thinking about solving a problem, then I’d wake up with an idea in the middle of the night and go straight in to work,” he says.

On Fridays, he, his wife, Fran, and their two children would head to Fran’s family home, the Lewis farm in Truro.

“This was a real farm from the early 1800s into the early 20th century,” says a Truro Conservation Trust newsletter published in 2010. The original farmhouse was lost in a fire in the 1880s caused by sparks from a passing train, according to that report. The trust now has a restriction on the land, southwest of where Old County Road meets Ryder Beach Road.

But the ocean had drawn Sanders to these shores even before the farm did. He came to explore shipwrecks, diving with his father and grandfather, both longtime divers. “I dove on the Whydah 10 or 12 times,” he says, in the years after 1984, when Barry Clifford discovered the pirate ship that sank in 1717 off the coast of Wellfleet.

Sanders and his wife moved to the Lewis farm after he retired in 2006; their daughter Amy also lives on the property.

“Then I became a lighthouse keeper,” Sanders says. The Highland Lighthouse was automated by then, but for the next six years, Sanders brought visitors through and made sure the light was functioning properly.

It takes about 100 hours to complete a model ship, Sanders says. He has never made one from a kit. Because he builds models of specific craft, he seeks out blueprints of the original vessels, scaling them to a quarter inch per foot.

Sanders starts building his ships with “the keel, the ribs, and then I plank it out.” What he includes on the deck depends on the type of ship he is replicating. The work involves using a table saw, an assortment of smaller saws, and a lot of sanding, he says. The trickiest part is steam bending the wood for the rails. “I boil the wood in a frying pan,” Sanders says. “You’ve got to have it just right or it will snap.”

Sanders’s current project is a model of the Acorn, which he started about a year ago. “I have loved that story since I was a kid,” he says.

According to his version, the owner of the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company thought the railroad’s price to ship his glass to Boston was too high, and he threatened to build his own ship for the purpose. The railroad agent’s retort was, “Great oaks will grow from little acorns before you finish that ship.” After that, the glass company owner made good on his threat and ordered construction of a steamship, which he named the Acorn.