The house Marcel Breuer built in Wellfleet in 1949 represents the modernist ideal. It is above all simple. Pilings hold its small and seemingly lightweight box-shaped rooms just above the wavy pine-needle-carpeted slope down to Williams Pond.

Standing inside this modest assemblage of plywood and glass, a visitor feels a little naked, though in an enjoying-the-breeze way — a sensation the Bauhaus crowd would have approved. After all, Europe’s utopian craft revolutionaries were here escaping the demands of their academic and entrepreneurial lives. More moving, when you consider the evident joy in these artists’ and architects’ Cape Cod getaways, was that they were also escaping first an encroaching retrograde political climate, then war, then its aftermath in Europe. The Nazis closed the Bauhaus in 1933.

Being “the opposite of monumental,” as architect Peter McMahon and writer Christine Cipriani describe the modernist houses in their 2014 compendium, Cape Cod Modern, they are also fragile. That is evident in the Breuer house, where some siding has rotted and where a birch plywood ceiling has been peeled back for repairs.

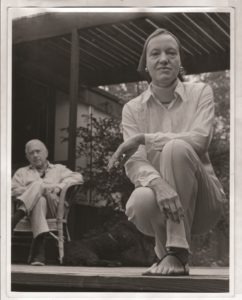

Still, there is a comfortableness to the house despite the damp that has snuck in and the mold that now has a foothold on some of the Homasote walls. The objects inside are one reason for that. Since Breuer died in 1981, his son Tamás, a photographer based in New York who now owns the house, has continued to visit, keeping in use both the furnishings his father created and the books he collected.

After years of discussion, Tamás has given McMahon’s nonprofit Cape Cod Modern House Trust the chance to buy the historic building along with Breuer’s objects, art, photographs, and hundreds of books on architecture and design.

The trust is known for its restoration of four other modernist houses, all in the Cape Cod National Seashore in Wellfleet, and for their use as places for creative retreat and scholarship. This is the first property the trust would own; the others belong to the National Park Service. And this is the first that is not an abandoned shell.

A Breuer table stands on a screened porch, its weightiness straining, perhaps, a room that’s cantilevered rather experimentally into the woods. The table’s base is homemade and rough: a stack of concrete blocks; its top is a thick slab of slate.

“He loved concrete blocks,” McMahon says, making a pitch for their readymade practicality. Then, “Imagine you didn’t know what they were and just look at them,” he says. Their oval-in-a-square geometry suddenly looks more captivating.

Next to the table are two side chairs made of tubular steel curved in a way that echoes the space: the cane seat is cantilevered. Its backside floats; a tiny bounce cannot be resisted. The knockoff you bought at the Door Store when you lived in Cambridge in the 1970s does not offer that.

Designed in 1928, the chairs were first manufactured as model B32 by Thonet, the Viennese company known for its bentwood café chairs, which were revolutionary in the 1850s. Later, the chairs got a new name, Cesca (Breuer had an adopted daughter named Francesca), when the designer’s manufacturing deal went to Dino Gavina’s Italian company. Gavina was bought by Knoll in 1968, which still produces the chairs.

What Breuer and other modernists mainly did in designing things was to pare them down to their essentials. Space rather than mass mattered. In the case of the Wassily chair, says McMahon, “It’s like he took a club chair and put it through a transmogrifier.” (McMahon’s choice of words reveals he is not only a Bauhaus scholar but a connoisseur of Calvin and Hobbes.)

Even if you have seen the chair or a version of it countless times, its transparency is new and breathtaking against the see-through side of the living room at the Breuer house.

The chair has a story that is partly about the Bauhaus designers’ search for adaptable and inexpensive materials — bentwood for the machine age. Mass-reproducible design for all was part of their philosophy. It is also about Breuer getting a bicycle. Riding his new Adler, he started thinking about how light yet strong his handlebars were, according to Christopher Wilk in Marcel Breuer: Furniture and Interiors (Museum of Modern Art, 1981). A plumber helped him weld the first tubular steel prototype in 1925.

The vinyl-padded Isokon long chair, with its wide, curved plywood arms that curl down and become legs, is a design that Breuer began working on in 1935 after following Walter Gropius to the London workshop of engineer Jack Pritchard. But it gave him trouble. Structural integrity, stability, and the pitch required tinkering through the 1960s. McMahon doesn’t know for sure but says the long chair at the Breuer house may have been one that was sent from the Knoll workshop when its designers created their version for him to critique.

If the trust raises the $2 million needed to make the Breuer house purchase — Tamás has given them a year, and the fundraising effort now stands at $1.25 million — its restoration will encompass the cataloging and organizing of these things that document the life of the house.

McMahon picks up a pair of iron candlesticks: because of their large scale, he thinks they were probably designed for a church and sent to Breuer here for approval. Breuer designed the St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minn. among other Benedictine outposts that might have been logical destinations for Brutalist altar decorations.

One by one McMahon is uniting the objects of modernism with their stories. “It’s like a fascinating shipwreck,” he says.