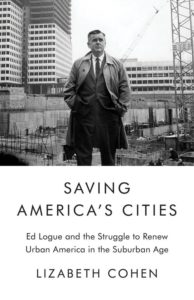

Urban renewal today conjures images of destruction and displacement. But in her most recent book, Saving America’s Cities, historian Lizabeth Cohen brings readers into the post-World War II mindset that conceived of urban renewal — full of liberal optimism about the power of the public sector to design cities with better housing and infrastructure. She takes a nuanced look at how the policy evolved, recognizing failures without dismissing urban renewal as misconceived or evil.

The book, her third, was published in 2019 and the following year won the Bancroft Prize, considered one of the most prestigious awards in the field of American history.

Cohen teaches American studies at Harvard but does most of her writing in Truro, where she and her husband, Herrick Chapman, also a historian, have owned a house since 2014. “The calm in Truro helps me live in the world I’m trying to create,” she says. “It really helps to be able to just escape into it.”

She was dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies from 2011 to 2018 and is a member of the board of the Payomet Performing Arts Center.

Saving America’s Cities revisits the familiar story of the rise of suburbs. “We historians have documented very well how suburbanization took off following World War II,” says Cohen. “Many people, and much capital, moved from cities to suburbs. And yet, we don’t really look at what happened to cities as a result of that massive exit.”

Cohen highlights the cases of New Haven, Boston, and New York, cities where urban planner Ed Logue knocked down, built up, and renovated with a heavy hand. In New Haven, he oversaw the demolition of three square downtown blocks to attract Macy’s department store. Boston’s Government Center, now considered by many a brutalist eyesore, was designed to signal the city’s midcentury self-reinvention. It brought in a badly needed influx of workers when it was built in the 1960s.

Cohen’s approach is not just to explain the policies behind urban renewal but to help readers understand the spatial and social realities of the cities where those plans unfolded. Cohen accomplishes this by making Logue — the New Deal liberal eulogized by a colleague as “Robert Moses and the anti-Robert Moses all at once” — the main character.

“Readers tell me that they really become connected to him,” Cohen says. She conducted 100 interviews with people who knew Logue, who died in 2000. She also studied his personal papers, which “were so extensive that I could have spent the rest of my life researching them,” she says. She is careful not to put him on a pedestal, but rather to “understand both what the vision was, and what the reality turned out to be.

“I don’t want to be an apologist for urban renewal,” continues Cohen. “The approach in 1950s New Haven — demolishing poor neighborhoods that were close to downtown to try to keep the middle class in the city — was replicated in many other cities in this country, like the West End of Boston. And it was a disaster everywhere. But I’m trying to show that it wasn’t all bad. By the early 1970s, what was happening in redevelopment reflected some learning on the job since the 1950s. Urban redevelopment was not just one unchanging disaster.”

This even-handed second look is especially needed right now. American cities are dealing with many of the same problems that they faced 70 years ago, when the Housing Act of 1949 set the goal of providing “a decent home and suitable living environment for every American.” According to a March 2021 report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the country don’t have enough affordable and available housing for households earning less than 50 percent of the area’s median income.

Looking for strategies to solve this problem, Cohen does not advocate that cities totally abandon making use of private capital. “We need to recognize that there are good and better and worse ways of doing it,” she says. “The conclusion that any federal investment in cities is going to be disastrous is just playing into the hands of the conservative right.”

The book has some applications to the Outer Cape. “Spending time in Truro has taught me that many of the issues I wrote about are not unique to urban areas or buried deep in the past,” says Cohen. “The most obvious is the one that Logue worked hardest on over his career: the need to provide more affordable housing. Remedies that Logue sought from the 1950s through the 1980s — such as more generous government subsidies for housing and greater community flexibility around zoning — are as needed now on the Outer Cape as they were in his time.”