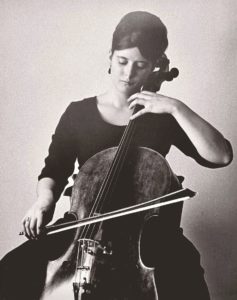

Carol Procter was only the third woman cellist hired by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The Boston Symphony Orchestra year was 1965, and Procter was in her early 20s, recently graduated with a master’s from the New England Conservatory of Music. At the time, the gender gap in American orchestras was considerable, though the BSO was making strides with blind auditions. “Today’s players would laugh to hear it,” writes Procter, “but management instructed me to make reservations in a separate hotel from the rest of the orchestra.”

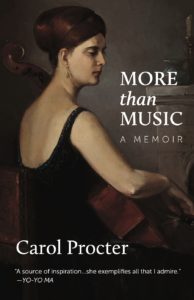

Procter’s trailblazing is sometimes overshadowed by an incident that happened when she was an undergraduate at the Eastman School of Music. She was arrested for being involved in a scheme to blow up the school with dynamite. She’d fallen under the spell of a charismatic but clearly unhinged fellow student.

“Some memories evoke the emotion of shame,” writes Procter. “I almost wanted to leave that part out. But it requires courage to share such memories with the world.”

Both tales are in Procter’s memoir More Than Music, published in October. The author lives at Seashore Point in Provincetown with her partner, Barbara, and suffers from a rare form of Alzheimer’s. The book was written with the help of Jeannette de Beauvoir. It has been praised by Yo-Yo Ma, who writes, “As a colleague, you exemplify all that I admire — your non-judgmental curiosity, your courage to speak truth, and your relentless pursuit of creating positive energy.”

The book is full of entertaining stories about conductors. “I have to be honest here about Arthur Fiedler: he was a lousy conductor,” writes Procter. “We used to laugh about him a lot, and because he was so difficult to deal with, we in turn made his life as difficult as we could.” Procter’s prankster stand partner once brought a laugh machine onstage. “Right in the middle of Clair de Lune, he turned it on, and the audience could hear the sudden ha-ha-ha of the machine,” she writes. Procter relates how John Williams called her “his favorite cellist” and has many tales of partying with Seiji Ozawa.

There are other fun tidbits, such as Procter’s love of Earth, Wind & Fire. “Does that surprise you?” she writes. “A classically trained musician loving this commercially successful band?” In addition to cello, Procter learned the viola da gamba, though she never strove for strict historical accuracy, playing with an endpin and overhand bow grip.

Procter writes frequently of her spirituality and becoming an “energy healer,” which feels at times out of place in the book. But in one chapter titled “The Ecstasy (and Business) of Music,” it all comes together. “In music, there is a process that transfers the energy from person to person through a vibrant electric connection,” she writes, “A passing of the baton from one to the next but always in perfect harmony.” From conductor, to musicians, to audience.

When Procter moved to Seashore Point, she rediscovered a recording, thought to be lost, that she made with pianist Mary Liz Smith in 1991. “It included a piece I’d practiced over and over as a young student, Fauré’s Après un Rêve,” she writes. “The piece is sad, but beautiful and powerful. It stirs strong emotions, touches the heart — the kind of music I truly love.” She made a CD called Lost Treasures in 2018, a portion of which can be heard on SoundCloud. Her performance of Sibelius’s Valse Triste is sensitive but never oversentimental, the chromatic passages tossed off with ease.

“Ever since I retired, people kept asking me if I could play for them,” writes Procter. “That, I explained, had been a different season of my life. It had been wonderful, but seasons change. I had sold my cello and hadn’t played since leaving the orchestra.” Procter is currently enjoying her season as a writer and artist (she makes collages about her experience with Alzheimer’s).

“It’s fair to say that playing in the BSO is a stressful job,” writes Procter. While some players thrived in this perfectionistic and cutthroat environment, others found providing for their families in such a way exhausting. “Some stayed on even after they reached comfortable retirement age, afraid there might be nothing else for them to do,” continues Procter. “I could never understand that. For me, joy comes from listening to music, not just playing it. As long as my soul can dance, I will be just fine.”