PROVINCETOWN — Time is running out for Borislav Ivanov and his family. On May 15, the lease expires on the Commercial Street apartment where he, his wife, Iliana, and their three-year-old son have lived since October.

housing

TOWN MEETING

Truro Will Vote on Taking Motor Inn for Housing

Select board also approves a housing coordinator position

TRURO — Voters at annual town meeting on May 4 will be asked to authorize the town’s taking of the Truro Motor Inn at 296 Route 6 by eminent domain. The measure, which appears as Article 11 on the warrant, was supported unanimously by the select board and finance committee. It will require a two-thirds majority to pass.

The language of the article affords flexibility on how the property is acquired: “by gift, purchase, eminent domain, or otherwise.” According to Town Manager Darrin Tangeman and the select board’s explanation of the article, an eminent domain taking is the expected route.

“With the approval of Town Meeting, the Select Board intends to take 296 Route 6 (Truro Motor Inn) by eminent domain for the purpose of developing affordable housing, including but not limited to workforce housing,” the explanation reads.

For most of the last 10 years, the motel was home to about 50 people. Property owners David and Carolyn Delgizzi of Weston began renting out the building’s 36 rooms to long-term tenants in 2015 under their motel license.

But in 2018, inspections by the town’s fire, health, and building departments exposed a series of problems, including failed cesspools and overloaded electrical outlets. The rooms also lacked smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, and some housed more people than their size allowed.

The town took legal action against the Delgizzis in 2019 for failing to make ordered repairs. At the time, the town sought not to displace the tenants.

But in June 2020, the board of health did not renew the Delgizzis’ motel license, initiating a series of evictions.

The final tenants were forced out last July. Nicholas and Angela Rose and their two children had lived there for seven years.

The select board and board of health held a joint executive session on Aug. 1, 2023 “to consider the purchase, exchange, or lease or value of real property.”

Back Taxes

Seizing a property by eminent domain requires having its value appraised and paying the owners “reasonable compensation.” The Truro Motor Inn’s current assessed value is $1.17 million.

Tangeman said he does not expect the purchase to require a Proposition 2½ override. According to the warrant article, the select board plans to use existing funds to pay for the acquisition. The Dennis Family Gift Fund, which includes settlement money from the owners of an illegally built house, and the Affordable Housing Trust Fund are both likely revenue sources.

“The article itself is written in such a way where we can seek to purchase this without raising taxes,” Tangeman told the select board on March 26.

The town would also recoup the property’s unpaid taxes, Tangeman said. As of March 29, Delgizzi owed $50,710.96 in back taxes on the Motor Inn, said Caitlin Gelatt, Truro’s tax collector and assistant treasurer.

“We pay ourselves first and then pay the Delgizzis for the appraised value,” Tangeman told the Independent.

The Truro Motor Inn is one of five Truro properties owned by Delgizzi, all of which are in arrears on taxes. Delgizzi owes about $515,000 in Truro real estate and personal property taxes in total, Gelatt said, but the unpaid taxes on other properties cannot be collected through the taking of the Inn.

“This is one of my favorite parts of the warrant,” said select board chair Kristen Reed. “From everything I’m hearing, this is something we can all get behind.”

Reed said she had been asked about the other Delgizzi properties in Truro. “The board is aware that constituents have concerns, and we can only address one [Delgizzi property] at a time,” she said.

Housing Coordinator

On March 19, the select board voted unanimously to add a full-time housing coordinator to Truro’s town staff, funded by increased short-term rental registration fees. The new position would not require a budget override, as revenue collected between March and July is expected to pay for the position.

In February, the select board doubled the short-term rental registration fee from $225 to $450. The town is also cracking down on unregistered rentals using software from the municipal contracting firm Avenu, which will bolster the revenue stream, according to Tangeman.

Last year, a Proposition 2½ override article to fund a housing coordinator passed easily at town meeting but failed at the town election by 96 votes.

“The purpose of the ballot was the funding,” Tangeman told the select board — indicating that voters had supported the job but didn’t support the funding mechanism.

Truro will follow in the footsteps of Eastham and Provincetown in adding town staff dedicated to housing. In Wellfleet, housing work is wrapped into the town planner’s job.

Lisbeth Wiley Chapman, 80, spoke to the need for a housing coordinator in public comments at the March 19 meeting. Chapman said she still works and is “the picture of the older single women that need affordable housing.

“My reason for speaking tonight is to give you a face of people who contribute to the community but can’t deal with the increases in rent,” Chapman said, adding that rent takes half of her fixed income.

Chapman said a housing coordinator could help bring in more state funds and grant money. “I laud you completely for this position,” she said.

Kevin Grunwald, chair of the Truro Housing Authority, also praised the decision to move forward with a housing coordinator, which was a priority in the town’s draft housing production plan.

In the past two decades, only 19 new units of affordable housing have been built in Truro, Grunwald said: the 16 units at Sally’s Way and three Habitat for Humanity homes.

“As the chair of the housing authority, I’m ashamed that we have not been able to do better,” Grunwald said. “We truly do need a staff person in this position.”

Staff Under Pressure

Tangeman said he expects to fill the housing coordinator position in June or July. The wait has to do with an understaffed town hall, he said.

“We’re at negative capacity,” said Tangeman. “People are working probably 10 to 20 hours extra per week just to meet requirements.” Tangeman said he would post the position after town meeting and town election wrap up in May.

The town’s two executive assistants, Noelle Scoullar and Nicole Tudor, told the select board there was a year-round need for more staff.

“Our current workload is well over the maximum capacity of 40 hours per week,” Tudor said. “We manage the current day-to-day tasks and communication with the public by eliminating lunch breaks.”

Town meeting voters will also consider a Proposition 2½ override to fund a human resources coordinator and a free cash transfer to fund a part-time climate action coordinator. There is also a proposed free cash expenditure for “records access consulting” that will fund a contractor to help the town clerk with a recent surge in public records requests.

CERTIFIED

Eastham Takes on the Housing Management Problem

Seven units owned by the affordable housing trust will be managed by town staff

EASTHAM — Last July, the Eastham Affordable Housing Trust’s housing management contract with the nonprofit Community Development Partnership (CDP) expired, and the trust didn’t renew it. Instead, it decided to have town staff manage its seven properties alongside the six town-owned units that Eastham already managed.

Jay Coburn, CEO of the CDP, and Jacqui Beebe, Eastham’s town administrator, had different assessments of the wisdom of that change.

“Property management in general is a problem,” Coburn said. “If you mess it up, you risk losing the tax credit, and that’s a disaster.”

Town staff “were concerned there wasn’t a lot of capital improvement being done,” Beebe said. The properties required more maintenance than they were receiving, she added.

The CDP had been managing the trust’s properties since 2013. The decision not to renew the contract came after the town hired a housing coordinator, Rachel Butler, in December 2021. She was qualified to perform the same management functions that the CDP had been contracted for.

Management of affordable and income-restricted units has spurred debate on the Outer Cape before.

The question of who was responsible for checking on Wellfleet’s income-restricted accessory dwelling units flummoxed town staff last year when a year-round tenant was evicted by new owners who listed the main house as a short-term rental and took the ADU for themselves.

Wellfleet’s income-restricted ADUs had been monitored by the CDP until another contract changed; afterwards, Wellfleet’s assistant town administrator and building commissioner each said the other was in charge.

In Provincetown, the management contract for the 26 market-rate rentals at the Harbor Hill complex will soon be put out to bid again — but not before a separate request for proposals is issued to see if any property management companies want to buy the complex outright.

“We spend a lot of time talking about building affordable housing, but we don’t pay a lot of attention to the management of it,” said Kristin Hatch, executive director of the Provincetown Housing Authority. As towns create more housing, they must assess the benefits of management by nonprofits, private companies, or in-house staff, she said.

‘The Queen of Management’

Eastham’s changeover is resource-efficient and will improve the quality of the housing, according to Beebe and Eastham Affordable Housing Trust chair Carolyn McPherson.

But a CDP director said it could create more work than the town can handle.

“I generally encourage towns to not own and manage their own properties,” said Paul Ruchinskas, treasurer of CDP’s board and former affordable housing specialist at the Cape Cod Commission. “Typically, towns don’t have the capacity to do it.”

Finding property managers who can do income certification is particularly difficult, Ruchinskas said.

It’s “the toughest skill set to find,” and if there is turnover in the role, finding a replacement “will be one of the hardest challenges for the town over the long haul,” he said.

Before coming to Eastham, Butler was a property manager for 12 years at Community Housing Resource, an affordable housing developer based in Provincetown.

She was “the queen of management,” said Hatch — a “known commodity” and an asset to the region’s housing efforts.

In Eastham, Butler is currently in charge of relatively few units — six owned by the town, including two that were bought in 2022, and seven owned by the trust.

“She managed many more units than that for Community Housing Resource,” Hatch said.

Hatch is the sole property manager for the Provincetown Housing Authority (alongside a maintenance technician and an administrative assistant), which has 46 units; she also administers 26 state vouchers.

Ruchinskas acknowledged that the small number of units will make it easier for Butler to manage the properties. “The fact that it’s all located in Eastham just makes it a heck of a lot easier to deal with,” he said.

Out to Bid

Ruchinskas also said that for towns to maintain or improve their housing they must go through a procurement process outlined by Massachusetts’s Chapter 30B, which states that all town contracts must be offered for bidding by different vendors to guarantee fairness.

That process is “cumbersome,” said Coburn, and CDP already has two maintenance technicians on staff.

Larger improvement projects will be subject to 30B, Beebe agreed — though she said that would still be the case if a nonprofit were managing the units.

Any town-owned property is subject to 30B, Beebe said, since “it is still a public asset.”

Eastham also has facilities and maintenance workers in its DPW. They can supply day-to-day services, from fixing broken amenities to “something very simple, like plunging a toilet,” Butler said, and the town doesn’t have to bid out such urgent repairs.

In years to come, the larger housing projects at the T-Time, Town Center Plaza, and Council on Aging parcels will likely be managed by their developers, McPherson said.

Beyond those projects, Eastham has also endorsed a “scattered site” approach to affordable housing, seizing the opportunity to purchase individual units when they become available, Beebe said.

The scattered site approach was challenging for CDP’s technicians, who “spend 40 percent of their time driving,” according to Coburn.

Projects like the Village at Nauset Green, a 65-unit complex managed by the multi-state developer Pennrose, are easier to manage because the units are close together and nearly identical, Coburn said.

News Editor Paul Benson contributed reporting.

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Truro’s Cloverleaf Faces up to $7M Funding Shortfall

Developer asks to increase the number of units from 39 to 43

TRURO — Construction at the Cloverleaf project at 22 Highland Road has yet to begin, seven years after the state transferred the 3.9-acre property to the town specifically for affordable housing. The development’s total cost is now projected to be $27 million to $28 million, leaving the project with a funding shortfall of between $4 million and $7 million, according to developer Ted Malone.

In December 2022, when the project received more than $16 million from the state Dept. of Housing and Community Development, construction was expected to begin in summer 2023.

Several factors contributing to the delay, Malone said, include increased construction costs and the effect of higher interest rates on the developer’s borrowing ability.

“The impact of interest rates getting up to 6, 7, 8 percent reduces the amount that we can borrow with the same amount of cash flow that the development has,” Malone said. He is the founder and president of Community Housing Resource of Provincetown, the developer of numerous affordable housing projects on the Outer Cape, including Sally’s Way in Truro.

Construction costs first shot up because of supply-chain hitches during Covid, but there was hope that they would drop again, he said. That didn’t happen. “What we had hoped would return to normal has just been increased construction costs even though the supply is fine,” Malone said.

Costs have also risen because Truro is so remote, he added. “Funding sources don’t consider our costs to construct to be as high as in metro Boston,” though that’s not accurate, he said. Malone pointed specifically to the qualified allocation plan for the low-income housing tax credit program released by the Mass. Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities. Finding workers and large contractors is an obstacle on the Outer Cape, he said.

According to the comprehensive permit issued by the zoning board of appeals, the Cloverleaf development’s 39 units will serve a mixed-income community, with tiered median income restrictions of 30, 60, and 100 percent. The project as approved would include 12 duplexes with a total of 24 units and a 15-unit apartment building. There would be a combination of one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments.

But on Tuesday Malone said he had submitted a request to the ZBA for a small increase in the number of units, from 39 to 43. The development’s footprint and the total number of bedrooms wouldn’t change, said Malone. Rather, four of the planned three-bedroom units would be split into one- and two-bedroom units.

That modification would not only better meet the need on the Cape, where there is less demand for three-bedroom units, he said, but may also help with securing additional funding. “All of these units would have to be in the lower income tier to get the subsidy resources that we want,” said Malone.

The developer is asking the ZBA to consider the alteration “an insubstantial change,” which the board can decide “within the context of their original approval,” Malone said. If that request is denied, the ZBA will have to hold a public hearing on the change.

Plans for wastewater treatment and stormwater drainage will not change, according to Malone. “All of that has got to stay the way it is because that had rigorous review,” he said.

About a year ago, the project received $1.3 million in ARPA funds, Malone said. “That helped, but costs have continued to go up since then.”

Community Housing Resource is newly working with the Waltham-based contractor Delphi Construction. Malone said they are in the process of “value engineering, trying to make the construction more efficient, less expensive, finding areas where maybe we can save.” The proposed shift in the number of units is part of that process.

“Cloverleaf is a case study in why small-scale mixed-income housing development is so challenging to realize,” said state Sen. Julian Cyr. “It is incredibly disheartening that the state transferred this parcel to Truro seven years ago and not a shovel has gone into the ground.”

Malone hopes he won’t have to wait until town meeting in May to secure more funds because that would further delay construction. But it’s unclear whether there is more money available from the town’s Affordable Housing Trust, he said, and funds are scarce at the county level. There are also possible state avenues, like the Rural and Small Town Development Fund, whose grants might help with “the hard costs of infrastructure,” Malone said.

Town Manager Darrin Tangeman said he has been working since December to schedule a meeting with Cyr, state Rep. Sarah Peake, and Malone to discuss funding possibilities. The meeting is likely to take place on Jan. 29, Tangeman said Tuesday.

“To date, the town of Truro has not had to spend a significant amount of money to realize Cloverleaf, aside from legal fees related to frivolous lawsuits that were thrown out of court,” said Cyr. To realize future small or medium-size mixed-income developments, he said, “Truro may need to follow the example of Provincetown, Nantucket, and Martha’s Vineyard towns that have made direct appropriations in the budget to subsidize housing.”

The waiting list for the 16 units at Sally’s Way currently has about 200 people on it, according to Kevin Grunwald, chair of the Truro Housing Authority. That’s a “ballpark” number, he noted.

Tangeman feels the urgent need for housing in his town hall office.

“I’m seeing the challenges of recruiting town employees due to the lack of affordable or even workforce housing in Truro and in the region,” he said, mentioning the shortage of health-care workers as well. The struggle to recruit workers “is playing a role in my support” for the Cloverleaf project, he added.

Malone is hoping to see sufficient funds committed by August, with shovels in the ground by September. Construction is currently projected to take 22 months, he said.

“I’ve been such a big fan of having at-scale development at Walsh and other parcels across the region because we can maximize state and federal resources that are available,” Cyr said. “Even once we cut the ribbon on Cloverleaf, we’ll still have a major housing crisis here.”

HOUSING

Workshop Offers a Preview of Town Meeting Agenda

Zoning changes and a ‘Lease to Locals’ program are on the docket

PROVINCETOWN — The town’s “housing workshops” — periodic joint meetings of four committees plus town staff that began in 2021 — have become a kind of drafting room for town meeting, a place where policy ideas can be discussed and refined before they are placed on the warrant for voters.

Proposals that have passed through these workshops have fared exceptionally well at town meetings, including the short-term rental bylaw that was written by town counsel and passed overwhelmingly by voters on Oct. 23.

In the wake of that vote and the town’s purchase of nearly an acre on Nelson Avenue, there was a relatively short agenda at the Dec. 4 housing workshop, which took under 90 minutes. Members of the select board, planning board, community housing council, and Year-Round Market-Rate Rental Housing Trust expressed a broad openness to the zoning measures and “Lease to Locals” incentive program that town staff presented.

The meeting opened with a discussion of the housing needs assessment survey that the UMass Donohue Institute is preparing to undertake next spring. The assessment is slated to cost $53,200 and will attempt to define how many units the town needs “to meet the demands of municipal employees, essential workers, year-round residents, and other target populations.”

Nearly every board that deals with housing has complained recently that it does not know enough about the income levels of various kinds of workers in town, making it hard to allocate resources between “affordable housing,” which serves people making up to 80 percent of area median income (AMI), and “market-rate housing,” which serves people making between 80 and 200 percent of AMI.

(In Barnstable County in 2023, the 80-percent-of-median-income threshold that divides “affordable” from “market-rate” housing was $67,700 for a one-person household and $77,400 for two people.)

The town currently has $1 million in rooms tax money allocated for housing, Town Manager Alex Morse said, and workshop participants agreed that to allocate that money wisely the town should know more about the people it’s trying to serve.

Several participants said the town should use the survey to ask how much rent people were paying in privately owned rentals in town — but not necessarily to develop a target for the town’s market-rate rentals.

“We need to collect data and understand the current market-rate rents — that’s valid, and we should know that,” said planning board chair Dana Masterpolo. “But I think we should start with the people who are currently without housing, the EMTs and police officers and schoolteachers, and ask what they earn.” Setting rents relative to those peoples’ wages “so that they can live, not just survive” should be the goal, she said.

“I agree,” said Morse, “and the goal of the survey is to collect income information and work backwards to find the appropriate rents for people that are housing insecure.”

‘Lease to Locals’

Provincetown’s Deputy Housing Director Mackenzie Perry described “Lease to Locals” — a cash-incentive and tenant-matching program designed to persuade the owners of short-term rental properties to lease their homes to long-term tenants instead.

“People would have to currently be using their property as a short-term rental, and then we would offer the monetary incentive for them to convert it into a year-round lease for folks who work in the area,” Perry said. There would be caps on what the owner could charge in rent, and there could be a bonus payment if the owner agrees to rent for a second year.

“We don’t think this will meet 100 percent of the need, but it could be a bridge to the new construction that’s slated to be online in a couple of years,” said Morse. Even one or two dozen new leases would be significant, he said.

Placemate.com, the company that administers the program, was founded in Truckee, Calif. by Colin Frolich, a former marketing director of Airbnb who moved to Lake Tahoe in 2018 and was surprised he could not find a year-round rental.

The financial incentives are typically funded with short-term rental tax revenue and range from $5,000 for a one-bedroom unit in Eagle County, Colo. to $18,000 for a one-bedroom unit on Nantucket.

Nantucket’s program began last August and is the first to be entirely funded by private donors. Additional rules state that the tenant must either work on the island or be disabled and cannot be employed by or related to the property owner.

“We’ve asked them to submit a proposal,” Morse said, “where based on other communities with a program, they do some predictive analysis on how many units we might get in the first year and what it would cost.

“Then that’s something we can all look at and tinker with” at the next housing workshop in January, Morse said, “and really consider if this is something we want to invest in.”

Zoning Measures

Community Development Director Tim Famulare presented six zoning measures, five of which would liberalize rules for the use of residential parcels.

One would allow small accessory dwelling units, or ADUs, to broach the setback areas at the edges of residential lots under the same rules applied to garden sheds. Another would allow two-family housing by right in the Res-2 district, rather than by special permit from the planning board, and three-family housing by right in the Res-3 district.

A third measure would slightly reduce the number of projects in the Res-3 district that require site plan review. A fourth would relax the lot size requirements that restrict the placement of two or three homes on a lot in the Res-2 and Res-3 zones, while a fifth would allow inhabited recreational vehicles on driveways in the Res-1 zone.

The sixth measure, an amendment to the town’s inclusionary bylaw, would increase the number of units required to be affordable in new residential developments from one-sixth (16.67 percent) to one-fifth (20 percent).

“I feel like I say this every time we come together, but I don’t think we should have single-family zoning in town anymore,” said select board member Austin Miller. “I think we should make this go a little further and have two-family, or two single-family dwellings, in Res-1 in addition to Res-2.”

Denser housing sells for less than single-family homes, Miller said, making it more “naturally affordable.”

Masterpolo asked for a bylaw that would specifically allow large market-rate rental projects, such as the one slated for the site of the old police station on Shank Painter Road, to be built. That project relied on a four-story allowance on Shank Painter that does not exist elsewhere in town, Masterpolo said, and it also had to include affordable units to qualify under the town’s inclusionary bylaw.

“I would say, ‘Stay tuned,’ ” said Famulare. The town is working with the Cape Cod Commission to develop a model year-round rental bylaw that could be ready in time for spring town meeting, he said.

Morse closed the meeting by asking the boards to come up with more ideas and send them to town staff before the January housing workshop.

“If there’s certain ideas or language you want us to take a look at, we’re happy to do some legwork and help them get to a better place,” he said.

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Two Small Housing Projects Make Slow Progress

Properties bought by the town 18 months ago need at least another year

EASTHAM — It will be at least another year before two properties the town voted to buy in May 2022 and convert into affordable housing will be ready for tenants, said Town Administrator Jacqui Beebe. The drawn-out and costly process of renovation to create what will likely be six units in this case illustrates how small-scale affordable housing efforts can soak up scarce time and resources— at least according to some housing advocates.

EDUCATION

Housing Crisis Hits Schools — and Will Get Worse

Enticing new staff to towns where teachers can’t live is ‘a really hard sell’

Faced with significant turnover of teachers, administrators, bus drivers, and support staff, every one of the Outer Cape’s schools is feeling the effects of Cape Cod’s year-round housing shortage.

When talking with promising applicants, “one of the first things we ask is ‘Do you have housing?’ ” said Gerry Goyette, superintendent of Provincetown International Baccalaureate Schools. “Because that is the first concern.”

“If they don’t have housing here, it’s a really hard sell,” said Brooke Clenchy, superintendent of the Nauset Regional School District, which still has a number of vacancies for the school year ahead with opening day for staff on Sept. 5 and day one for grades K-12 on Sept. 7.

At Truro Central School, many teachers have been forced to find housing up Cape, said Supt. Stephanie Costigan. Some now come from as far away as Sandwich, she said.

“I’m concerned about finding great new hires,” said Nauset High teacher Amy Kandall. She said the Cape used to be a sought-after destination for teachers. “We would get really qualified people here because it’s a big draw to live in such a beautiful place.”

There’s been another shift, too. Once teachers are hired, retaining them can be difficult because of the cost of housing. Nauset Regional Middle School teacher Sean Kirouac said the school, which is in Orleans, recently hired a couple of teachers who quickly realized they couldn’t afford to live anywhere nearby. They left.

Kirouac described one colleague who is currently living in an apartment in her parent’s garage and is uncertain of her ability to ever find a place for herself. “She is really struggling with whether it is feasible for her to stay here,” he said. Losing her “would be devastating to the Nauset community,” he said.

Longtime residents feel the pull to move away for a different housing-related reason. Some turnover has come when school employees who have owned a home on the Cape and, seeing its high value, have sold and moved away, Clenchy said.

“You have this constant churn of people, and that’s not healthy for any organization,” said Clenchy. “You really need that stability of people committed and dedicated to the purpose.”

Kirouac said the turnover in staff is particularly difficult for students. “They thrive on consistency and rules and protocol,” he said. “When we constantly have a rotating staff and a rotating administration, kids don’t do well with it.”

The challenge of hiring and retaining employees is even harder when it comes to nonteaching staff. Chris Easley, chair of the Nauset Regional School Committee, said that while Nauset has done well filling open teacher positions — it filled all of the 74 positions that turned over before last school year — it has had a lot more difficulty getting applications for administrative positions.

And hiring other staff, like custodians, cafeteria workers, and bus drivers, who make less than teachers and administrators, is particularly difficult.

“We just can’t get them,” said Clenchy. “One of our positions at the high school is for groundskeeper. I can’t tell you how many times that position has turned over,” she said, adding that the situation is common across the district.

At Nauset, hourly wages for custodial and cafeteria staff range from $15 to $29 depending on the employee’s experience. The Cape Cod Collaborative, which provides busing for the Nauset and Truro schools, pays bus drivers around $30 per hour, according to the organization’s executive director, Paul Hilton.

Julie Packard, one of Cape Cod Collaborative’s drivers for Truro Central, said that because her position is part-time, her annual pay comes to around $25,000. “That’s nothing an average family could ever live on,” she said.

Even working full-time at that wage “is not enough to cut it to live here,” Hilton said.

According to the Wellfleet Housing website (created by the Wellfleet Affordable Housing Trust, the Wellfleet Housing Authority, and the Local Housing Partnership), the annual income required to buy a median-priced home in Wellfleet is $123,000, which is around $60 per hour for an individual full-time employee.

Hilton said the turnover rate of bus drivers used to be around 3 to 5 percent per year. Now it’s between 10 and 20 percent, and at any given time the organization could hire up to 20 more drivers if there were enough applicants, he said.

“Thirty years ago, people got trained and had to wait to get assigned a route,” said Hilton. “Now, we’re waiting for people to get licensed because we already have a route that needs to be covered.” The bus driver shortage has forced schools to cut extracurricular trips and merge daily bus routes, which causes students to be on the bus for longer, he said.

In addition to vacancies at the schools themselves, the staffing shortage in a variety of social services on the Cape affects students, Clenchy said. She said she was particularly concerned about the lack of mental health professionals on the Cape. “We don’t have the people to point [students] to,” she said.

The lack of housing has also affected the demographic makeup of school staff. Kirouac said the applications the school gets for teaching jobs are often from older teachers who own a second home on the Cape and are hoping to retire here. They get few applications from young people, he said.

Housing, Costigan said, is “the biggest obstacle” to efforts to diversify the school’s teaching staff. “Educators with more diverse backgrounds have expressed interest, but once they see the housing market and how much it costs, it tends to be a deterrent to them,” she said.

It’s important that students from diverse backgrounds have teachers that reflect that diversity, Kirouac said. But that is rarely the case at Outer Cape schools.

In Provincetown, for example, students of color make up about half of the school population, according to the town’s July sociodemographic survey, but the teaching staff is just about exclusively white, Goyette said.

Active community members have helped the schools get by. Goyette said Provincetown Schools has a network of people who tell the district when they hear of housing available to rent during the school year. Some homeowners especially want to help teachers, and those placements have allowed Provincetown to build a nearly full teaching staff, he said.

Kirouac said he benefitted from similar community support when he was able to buy his current house in Orleans at a price below other bids because the seller was a former teacher. But that happened only after he bounced around three apartments that were turned into short-term rentals and then, when trying to buy, lost four bids to cash-only offers.

More systemic solutions, such as reserving units of affordable housing for educators or offering subsidies to help teachers buy homes — which usually limits how much they can later sell the house for — are both difficult to implement and imperfect, Easley said. They don’t allow for the financial model teachers have traditionally followed, in which they buy a house and build equity while staying in the school system for a long period, he said. “There isn’t any good answer,” he said.

People working at the schools know that they are not the only ones who need housing. “It’s a systemic issue,” Goyette said. “There’s a need for housing across the board. I don’t think teachers are any more special.”

The future promises more challenges, Easley said. As older employees continue to retire, a true staffing crisis is on the horizon, he said.

“There is no doubt it is going to come, and it is going to get us good,” said Easley. “We haven’t taken the first baby steps to begin addressing it.”

DEVELOPMENT

Two Inclusionary Bylaw Projects Meet Different Fates

Both are now for sale, but only one received permits from planning board

PROVINCETOWN — A hotly-contested inclusionary housing project at 22 and 22R Nelson Ave. in Provincetown is currently for sale. After securing permits to build 12 townhouse-style condominiums on two adjacent parcels, developer Tom Tannariello has listed the properties and their accompanying permits for $1.45 million.

The parcels, totaling .58 acres, are currently under contract, and the permits are valid as long as construction begins before January 2026. Two of the 12 units will be affordable-ownership homes.

Another inclusionary project that Tannariello brought to the planning board in January has been permanently withdrawn, however.

The .68-acre lot at 8 Willow Drive has a 2,274-square-foot single-family house built in 1965. Tannariello proposed adding six units in four new buildings, leaving the single-family house in place. Under the inclusionary bylaw, one of those six new units would have been an affordable-ownership home.

That proposal was opposed not only by abutters but also by planning board members. Chair Dana Masterpolo told Tannariello she did not see any way the project could be adjusted to win her support, and he withdrew his proposal before it came to a vote.

That property is also now for sale.

22 and 22R Nelson Ave.

The listing for Nelson Avenue calls it an “extraordinary pre-approved building opportunity.”

Town Manager Alex Morse, who was a vocal supporter of the project, was happy to hear that the property was under contract. “I’m looking forward to seeing that parcel developed to make more housing available in our community,” said Morse in an email.

Tannariello’s permits for this project were hard-won. He filed the plan in December 2021, and the permits were ultimately granted in January 2023. Fifty-one letters were submitted, most of them in opposition. Residents also voiced their opposition during the hearings.

Verbal sparring extended into letters to the editor in the Independent. Morse himself wrote a strongly worded opinion piece published on Aug. 3, 2022, criticizing the planning board for discussing a possible scaling down of the project.

“This would not be the first time the planning board has responded to abutter complaints by reducing the number of units requested in an inclusionary project,” Morse wrote. “It makes no sense for the town to invest in drafting regulations to incentivize the creation of inclusionary housing if the planning board won’t embrace projects that fully comply with our zoning bylaws.”

He went on to say that there are few developable properties left in Provincetown. “If the planning board continues to let opportunities for housing slip by based on NIMBY sentiments, then the town will not be able to meet its housing goals,” Morse wrote.

The town’s housing council endorsed the project, and that panel’s vice chair, Austin Miller — now a select board member —urged its approval.

Neighbors had a multitude of concerns including density, traffic, parking, stormwater runoff, and effects on wildlife.

Tannariello’s decision to sell the property now that it is permitted is not unusual.

“In my years of experience in Massachusetts, I’ve found that it is not uncommon for owners of vacant property to obtain permits for potential future development, typically in order to make a property more marketable for resale,” said Town Planner Thaddeus Soulé.

Tannariello bought the property for $1.045 million in January 2019. He declined to speak to the Independent for this article.

8 Willow Drive

Tannariello purchased 8 Willow Drive in July 2021 for $1,165,000 and submitted his proposal for six new units alongside the existing house in January. Once again, he submitted his application for permitting under the town’s inclusionary bylaw, meaning one of the six new units would be deed-restricted to affordable ownership.

This time, it wasn’t just abutters who were opposed to the plan.

Planning board members said that clearcutting the property, widening the driveway, and installing two septic systems could contribute to the destruction of the dune. The parcel is almost entirely within the high elevation protection district.

Masterpolo stated her unwavering opposition to the project. Tannariello withdrew the proposal without prejudice in late February, leaving the door open for future resubmission.

He put the property up for sale in mid-June, however. It is now divided into two lots: one with the existing house on it and the other one vacant. The lot with the house is listed at $1,795,000. The vacant lot is listed at $749,000. If purchased together, the list price is $2,295,000.

HOUSING

Eastham Board OKs Closer Look at Tiny Houses

Changes in state rules may help towns take up small-scale solutions

EASTHAM — Tiny houses — often defined as dwellings smaller than 400 or 500 square feet — may be coming to Eastham if regulatory departments and the local zoning task force decide that allowing them would be one more way to address the shortage of housing in town.

Eastham won’t be the first community in the region to explore the possibility of allowing tiny houses. Nantucket approved a zoning bylaw allowing tiny houses in certain zoning districts in 2016. Although it passed muster with the state attorney general’s office and remains on the books, the state’s building and health codes prevented any from being built.

The zoning bylaw was approved by Nantucket town meeting voters thanks to a petitioned article written by Isaiah Stover. “I was single when I spearheaded the effort,” Stover said in an email on Sunday. Shortly after the bylaw passed, however, he got married and started a family. “I just didn’t have the time to continue to carry the torch.”

He hopes someone else will move the initiative forward.

Stover has watched the continuing housing crisis on the Cape and Islands and says he still would like to see the option of a tiny house become a reality.

In 2018, Provincetown voters approved a nonbinding petitioned article, proposed by Stephan Cohen, asking local officials to take a look at bylaw changes that would allow for “tiny house villages” and to develop bylaw proposals for the 2019 annual town meeting.

Those bylaw amendments would create a new designation of “tiny house village,” defined as a lot with multiple year-round occupied dwellings. Each unit would be under 500 square feet and sit on a foundation, even though most tiny houses are manufactured on wheeled platforms. The referendum asked that officials work to identify town-owned land for such villages.

A second article drafted by Cohen and approved at the 2018 town meeting called for urging then-Gov. Charlie Baker and the state legislature to take action on building code changes that would allow for tiny homes.

The legislature has since adopted Appendix Q of the International Residential Code used by Massachusetts. The appendix, which went into effect in the state in 2020, relaxes code requirements for tiny houses such as minimum ceiling height, regulations related to stairways, and rules related to lofts. One adjustment relates to skylights or roof windows that could be used as exits in an emergency. A tiny home is categorized in the code as having less than 400 square feet of floor area, excluding any loft.

Cohen said his concern over lack of housing prompted him to develop the petitioned articles back in 2018, but he didn’t know exactly what had happened with the tiny house study by officials. “I think the board did look into it,” he said. He did not remember the idea ever being rejected outright.

Provincetown Town Manager Alex Morse, who has been in charge for over two years, said he isn’t familiar with any study related to tiny houses. But he did have an opinion about their limitations: “Tiny houses are not a good land use when facing a housing crisis,” said Morse in an email.

“Town staff and the select board want to maximize density on any town-owned parcel that we envision for housing,” Morse said. He cited the affordable housing project being constructed on the former VFW property as an example. The town envisions something similar for the site of the current police station, Morse said.

Still, he didn’t entirely discount the value of tiny houses.

“Tiny homes, or some variation of them (ADUs or ‘sheds to beds’), would make sense in certain areas of town,” Morse said. “We are looking at our zoning map and other bylaws as to how we can encourage them on private property.”

Shana Brogan, Eastham’s projects and procurement director, would likely concur. She told the Independent that although Eastham has just begun its exploration of tiny houses, “Our initial thoughts are not necessarily a village.” They are more about “potential for the homeowner to put one on their property,” she said, as a less expensive alternative to accessory dwelling units.

That’s one reason select board chair Arthur Autorino enthusiastically supports a further look into tiny houses. “You don’t have to spend $700,000,” he said. “You can spend $60,000 or maybe a little bit more and end up with a nice house.”

Going forward, Eastham will not have to deal with the problem of conflicts with state building codes since those were resolved by the adoption of Appendix Q.

Hillary Greenberg-Lemos, the town’s new director of health and environment, told the select board, however, that tiny homes must be owner-occupied under state regulations — a rule local officials will need to consider as they develop new bylaws.

Town Administrator Jacqui Beebe said Brogan’s presentation at the select board’s June 26 meeting was to see whether the board was interested in pursuing a closer look at tiny houses. Now that it’s clear there is interest, Beebe said, a meeting to bring together the planning, building, health, and fire departments is the next step.

According to Town Planner Paul Lagg, bylaw changes to accommodate tiny houses would include a change to the town’s definition of “dwelling,” which sets the minimum size at 500 square feet, and an increase to the unit density to allow multiple dwellings on a single lot. The town’s long-term wastewater management plan would also factor into density changes, Lagg said.

“We may need to create a new category for smaller homes that are on foundations,” said Beebe, adding, “We used to call these cottages.”

MUNICIPAL PLANNING

VMCC Study Identifies New Housing Site in Parking Lot

Replacing parking spaces with housing looks easy, say Provincetown's consulting engineers

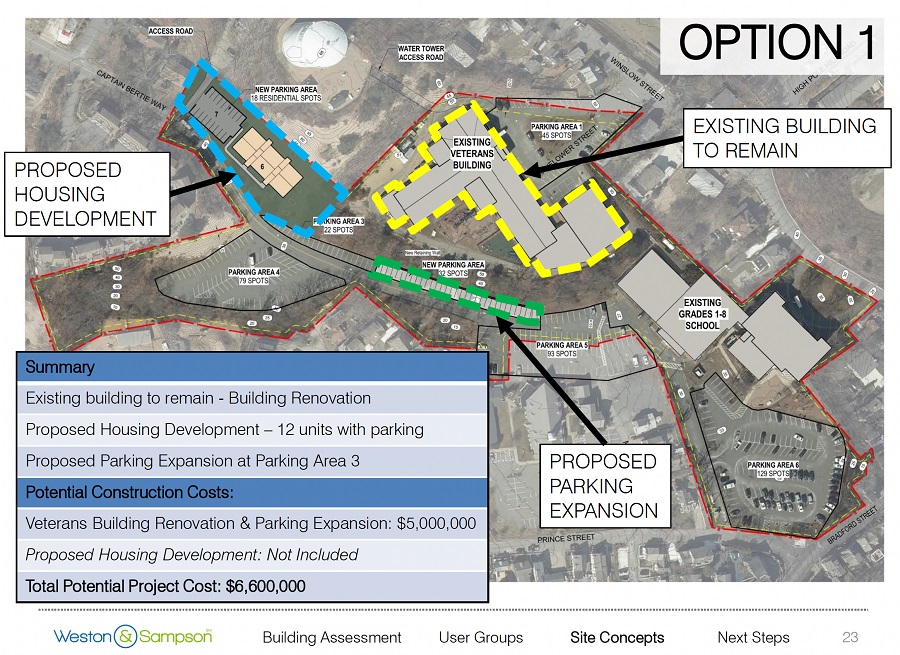

PROVINCETOWN — Engineers from the municipal contractor Weston & Sampson told the select board on March 27 that the town had three options for rebuilding the Veterans Memorial Community Center (VMCC) into a newer municipal building and new housing. They would cost between $36 million and $72 million.

But their top recommendation, called “Option One,” would be easier and less expensive: renovate the building instead of replacing it and pave the way for housing on a small parking lot on the property for around $6.6 million.

“I think we can take Option One, get something done faster, and that’s great,” said board member Leslie Sandberg. The rest of the board agreed, although they criticized the engineering report’s limitations.

“This is such a robust site for us to develop,” said member Louise Venden, “and it was my hope that we would be more imaginative and resourceful in figuring out what additional kinds of things we could put here. But obviously that isn’t what happened here.”

The Weston & Sampson presentation concluded the first phase of a study town meeting authorized a year ago. Last April, the town passed Article 21, which allocated $150,000 to study how best to redevelop the VMCC and its surrounding parking lots to meet needs for both housing and municipal spaces.

J.P. Parnas, the Weston & Sampson engineer who presented “Option One,” described it this way: The 37 parking spaces closest to Captain Bertie’s Way, which are downhill from the town’s main water tank, could be replaced with 32 new spaces further south by cutting into the slope in that region and adding a retaining wall. That would free up the northwest parking lot for new housing with its own dedicated parking, Parnas said.

The $6.6-million plan would include the retaining wall, the new spaces, and a package of renovations to the VMCC building but not the eventual cost of a housing project at the former parking lot, Parnas said.

The other three options presented by the consultants all involved bulldozing the existing community center, home of the council on aging, the recreation dept., dept. of public works, and the Provincetown Schools’ kindergarten classrooms.

Options Two and Three envisioned a two-story reconstruction of the one-story community center, which would free up room for parking at the site and therefore room to add housing on nearby parking lots.

A three-story community center with housing on its third floor and no other changes to the surrounding lots was presented as Option Four, with an estimated price of $72 million.

The select board was enthusiastic about building housing on the northwest parking lot — a project that would not have to affect the VMCC at all and could move forward relatively quickly, members said.

“I like the idea that we’re turning a parking lot at the bottom of the hill into a housing site,” said select board chair Dave Abramson, “but I don’t want to see a big renovation that’s going to stick us into this building for 20 or 30 years.”

“We found a new spot for housing,” said Sandberg. “But we still have this huge area, and you could go up pretty high, three stories,” and not affect the sightlines of neighboring buildings, she added.

Town Manager Alex Morse pointed out that the report also included a current-use analysis of the VMCC that found the building was well used by residents of all ages, from senior citizens to the town’s early-childhood program.

“There are things that need to be there that we can’t just find another place for, and I think we have an opportunity to make the existing VMCC last longer with a small investment,” Morse said.

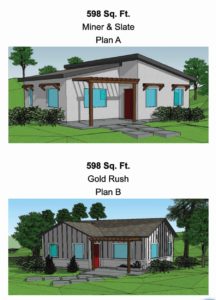

Option One has 12 townhouses with 18 parking spaces sited at the northwest parking lot, but Morse said that number was just a placeholder.

“When I first saw that, I said, ‘That’s not enough units,’ ” Morse said. He added that once the northwest parking lot is divided into its own separate parcel it would be easier to have a detailed discussion about density and unit count.

At present, the VMCC, the Provincetown Schools building, and five town parking lots all share the same 11.7-acre parcel. The northwest parking lot would come in at just under an acre, judging by the town’s documents, although a precise number was not provided in the report.

The town’s building committee, which was created to help shepherd a police station into existence, also spoke with Weston & Sampson’s engineers and with the town departments that work at the VMCC, chair Jeffrey Mulliken told the select board. Their conclusion was that relocating departments from the building during construction would be very difficult and that the building itself was in reasonable shape for continued use, assuming normal maintenance, Mulliken said.

Opportunity Zone Financing

Mulliken also told the board that he, planning board chair Dana Masterpolo, and two other people he did not identify were researching the possibility of enticing private investors to finance a market-rate rental housing project through the “opportunity zones” that were created in the 2017 tax law passed in the first year of the Trump presidency. Provincetown is the only opportunity zone on the Lower or Outer Cape.

“An opportunity zone is a place where wealthy people, people with large capital gains, can shield those capital gains from taxes,” Mulliken said. “The goal would be to build very high-density market-rate rental housing, because that creates a building that has income that an investor might be interested in joining.

“We’re in the very early stages, working out a proof of concept on this,” Mulliken added. “It would require some zoning relief for density. But I wanted to get it out on the table, and we could come back to you in two or four weeks and talk about it more.”

The board’s reception was cautious, although Morse pointed out that the town is hoping to build all market-rate rentals at the former police station site at 26 Shank Painter Road. “We’re likely to need local money and local interest,” Morse said, because the town won’t be seeking state and federal financing for that project.

Mulliken later told the Independent that he and Masterpolo, who each chair relevant committees, would not be financially involved in such an effort. He said he was not yet ready to identify the other two people.

“We’re starting out with a concept here, we have a lot of investigation to do, and this would have to be sanctioned by the town,” Mulliken said. “Dana and I are not developers — we’re just looking at this idea to see if it works.”

DEVELOPMENT

Land Court Ruling Makes Way for New House on Lieutenant Island

The ZBA is expected to follow judge’s reasoning rather than local bylaw

WELLFLEET — The zoning board of appeals is expected to reverse its decision of two years ago and approve a plan on March 9 for a 2,500-square-foot two-story house on the outer shore of Lieutenant Island where a 556-square-foot cottage once stood.

The board’s earlier decision was appealed to Land Court, where a judge reasoned that the town’s bylaw regulating nonconforming structures should apply in this case. During a straw poll taken on Feb. 23, four of five board members said they would vote in favor of the proposed construction.

The board delayed its formal vote because of an error on the submitted plans — they showed a stairway and a bulkhead even though the house won’t have a basement. Updated plans have been submitted, zoning board Chair Sharon Inger said this week.

The property, at 41 9th Street, has been in the Mandell family for about 100 years and is now owned by a few family members under a trust. In 2016, their small cottage was destroyed by fire. The family hoped to rebuild, but when that proved too expensive they put the 15,000-square-foot lot, now vacant, on the market.

In June 2020, the lot went under agreement to Donald Bliss and Damon Kirk of J&B Construction of Mashpee for $492,000. Under the agreement, which remains in place, the sale will be finalized when Bliss and Kirk secure a building permit from the town.

But the zoning board determined that the proposal the pair submitted in late 2020 for a 2,500-square-foot house to replace the cottage that burned did not conform to the town’s zoning requirements.

At the hearing two years ago, the board considered bylaw provisions that apply to pre-existing, nonconforming structures destroyed by catastrophe. Those require that rebuilding begin within a year and be completed within two years. They also stipulate that the rebuilt house be essentially the same as the one that was destroyed.

Attorney Christopher Kirrane, representing both the Mandells and J&B Construction, argued at that hearing that a special permit should be considered under a different provision that applies — catastrophies aside — to alterations of pre-existing structures on nonconforming lots. The zoning board denied the request by a 3-2 vote.

Bliss, Kirk, and the Mandells appealed the denial in state Land Court, and the proposal is back before the zoning board because of a decision by Judge Diane Rubin, who said that, under the town’s bylaws, the owner of a pre-existing nonconforming house can demolish it simply because they wish to have a different type of structure. This case illustrated that the zoning board’s initial decision would mean those who have lost homes involuntarily after a catastrophe would be subjected to “more Draconian regulation than those who simply want a larger house,” according to the judge’s statement.

At the Feb. 23 hearing, J&B Construction returned to the board with its 2021 plan, which faced opposition from one abutter on the potential environmental and aesthetic impacts of the proposed building.

Richard Thaler, who lives at 250 Meadow Ave. West, opposed the project when it was presented two years ago, and he remains opposed. He had joined the court case as “an intervenor” based on his easement to the project site. The location of the house would displace the easement, he said. Thaler questioned the effect the house would have on drinking water quality. Wells in the area have elevated sodium levels, according to Thaler.

Attorney Kirrane said the project already has the approval of the conservation commission. He argued that, because the new house will be built on land between two coastal banks, it will be an improvement over the siting of the original cottage. The old cottage had been perched on the coastal bank and its footprint extended beyond the property line onto a nearby paper road.

Thaler’s attorney, Sarah Turano-Flores, sent a letter to the zoning board last month saying that J&B’s proposed house would be one of the largest on the island. Only four were larger, she wrote, and their lots were nearly double the size of the target property.

Kirrane argued that Turano-Flores’s figures took only square footage into consideration. The footprint of the proposed house was only 12 percent of the 15,000-square-foot lot, Kirrane argued. Smaller houses on the island standing on smaller lots cover higher percentages of those lots, he said.

Restoration ecologist Seth Wilkinson, who has worked on Thaler’s property to stabilize the coastal bank, said removal of the existing vegetation to build the house will remove deep root systems that are “the best remaining protection for coastal stabilization, filtration of stormwater, and preservation of high-value wildlife habitat.”

Jen Crawford, a land management consultant who had represented the Mandells during the conservation commission’s review two years ago, accompanied Kirrane on Feb. 23. Crawford had developed the restoration and replanting plan for the Mandell site. The commission felt that the project would be a net benefit, she told the zoning board. “There would be a net increase of vegetation on this property,” she said, “as well as an increase of vegetative buffer to the coastal bank on both the east and west side of the property.”

When issues related to stormwater from the property eroding the bank were raised, Crawford said the project site sits lower than the coastal banks. “There’s literally no way overland flow from this site can possibly get to the coastal bank,” she said.

While Turano-Flores raised the issue of an easement on the project site used by Thaler, zoning board Chair Sharon Inger said that wasn’t a zoning issue. “It’s an issue that is to be decided between the two private parties,” she said.

Inger and fellow board members Jan Morrissey and Trevor Pontbriand and alternate member Reatha Ciotti voted to grant a special permit in a straw poll. Wil Sullivan cast the only opposing vote, saying that he believed the adverse effects of the plan far outweighed the benefits. Those same board members will take a final vote on March 9.

HOUSING

Settlement Ends Court Fight Over Patrick’s ‘Barracks’

Negotiated project changes will need approval from regulatory boards

PROVINCETOWN — It has taken time, money, and willingness to compromise, but local businessman Patrick Patrick should be able to break ground by summer on his much-anticipated, mostly seasonal workforce housing complex known as “the Barracks.”

The four abutters who appealed the town’s approval of the project in 2021 in Barnstable Superior Court have reached a settlement agreement with Patrick, putting an end to 19 months of litigation. “It’s a great relief to be done with the lawsuit,” Patrick said last week.

Patrick’s proposal is for a three-story building on his property at 207 Route 6 that will include 28 four-person dormitory units, housing as many as 112 seasonal workers, and 15 year-round apartments. The plan also calls for one two-bedroom manager’s unit.

The number and mix of apartments were not changed under the settlement agreement, but Patrick did agree to several design changes during the negotiations, which the abutters’ attorney, William Henchy of Orleans, called significant: balconies will be removed from units on the side of the building closest to the abutters; roof decks will be moved to the other side of the building; and Patrick also agreed to some changes to the lighting plan.

“I give a lot of credit to Mr. Patrick for addressing the concerns of the neighbors,” said Henchy, who represents Judy and Alison Gray, John Crowley, and Jay Gurewitsch.

One big point of disagreement was Patrick’s plan to use Province Road, which is a private way, as one point of access to the apartments. Patrick has agreed to limit his use of Province Road to emergency vehicles only along with providing access for walkers and cyclists, Henchy said. Patrick has also agreed to chip in on maintenance of the road.

Patrick confirmed those details of the settlement in a phone interview last week. The main access to the project will be from Route 6, he said. He confirmed that “there was a financial component to the settlement” but declined to state the amount. According to Henchy, Patrick agreed to pay $75,000 to the abutters to cover their legal fees.

The lawsuit and settlement negotiations have been expensive, Patrick said. “It’s very time consuming, and when everyone has got lawyers working on it, it’s going to be a lot of money,” he said.

Patrick’s attorney, Gregory Boucher, said Friday that new plans reflecting all the changes have been drawn up and would be submitted to the planning and zoning boards within the next few days. “I’m not sure if they will require a full hearing,” Boucher said. “The town could consider them minor modifications.”

Town officials have been supportive of Patrick’s plans. The select board issued an economic development permit in 2019, allowing 9,645 gallons per day and hookup to the municipal sewer system for the project. The zoning board approved relief from parking requirements and building scale regulations in 2020 and 2021. The planning board unanimously approved the site plan and granted a required special permit in mid-2021.

The court case was one of the first in which judges required those appealing a permitted housing project to post a bond under the provisions of the state’s Housing Choice Act. While the statute allows for bonds of up to $50,000, Barnstable Superior Court Judge Thomas Perrino ordered the appellants in the Barracks case to post a $15,000 bond. That money is being returned to his clients, Henchy said.

The court has agreed to allow 120 days for the two sides to file for dismissal of the case, which will be done once the town’s review is completed to both sides’ satisfaction. “If the review is not completed or the boards reject the plan, I might have to litigate,” Henchy said.

But Patrick said he is confident the project will now move forward. “I do believe the town administration has expressed support, and, at this point, all the neighbors have agreed,” he said.

Assuming the review proceeds smoothly, construction would begin this summer and take about 18 months, Patrick said.

AGENDA-SETTING

Provincetown Aims Higher on Local Housing Policy

At housing workshop, ideas from other resort towns, and a cry for help

PROVINCETOWN — With Hanukkah already underway and Christmas less than a week off, Monday night was not the most likely time to find 60 people at a meeting on housing. Nonetheless, on Dec. 19 the select board, community housing council, and Year-Round Market-Rate Rental Housing Trust met with town staff, the housing directors of Vail, Colo., Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket, and several dozen members of the public for a three-hour session about the gravity of the crisis here and new ways to address it.

The first hour featured a presentation from George Ruther, housing director in the resort town of Vail, which began an ambitious community housing program in 2017.

“For the town of Vail, housing has been a decades-long problem,” Ruther said. In 2017, the town council decided they were tired of talking. “They wanted to do something direct and specific about it,” he said.

Vail created and staffed a housing department in town government and a housing authority to oversee it, Ruther said. The town defined a new type of deed restriction that does not involve income limits or resale rules but instead requires that the actual occupant of the unit (not necessarily the owner) live and work in the county. Then, the town set a goal of 1,000 new deed-restricted units in the next 10 years.

Vail now has 175 of those deed-restricted units, Ruther said, housing 390 people. The total cost has been just over $12 million, with a per-unit cost around $69,000. Last year, the town’s voters approved a dedicated half-percent increase in the town’s sales tax, Ruther said, which will generate almost $4 million per year specifically for the town’s housing program.

“We’re using the housing stock we already have to address our housing challenge,” Ruther said. “We see this as a very cost-effective program.”

Vail and its neighboring resort towns had already been using inclusionary zoning to get affordable units into new projects, Ruther said, and pursuing conventional affordable developments as well, but those strategies had not been enough. Ninety percent of homes in Vail were being sold to people who don’t live in the county, and without enough people to work, it was becoming impossible to maintain the town’s economy.

“We believe housing is critical infrastructure,” Ruther said. Vail now funds its housing programs at the same priority level as its roads, schools, and emergency services.

Public Comment

After a half hour of detailed questions from board members and staff, Ruther signed off, and the workshop switched gears to public comments. Twenty people spoke over the course of the next hour. Collectively, their comments were both a push toward bold action and a bracing reminder of the human costs of a housing crisis.

Heather Duncan, a physician’s assistant at Outer Cape Health Services, broke into tears while telling the workshop that her patients’ traumatic experiences of displacement were now happening to her as well.

“One of my patients who was working three jobs here had to leave when her place was sold and the new owners wanted to Airbnb it out,” Duncan said. “She said something I will never forget: ‘I don’t know what will happen to me.’

“Now it’s my turn,” Duncan went on. “For the second time this year, I need to find a new place to live, and I do not know what will happen to me. I want to explain to you how it feels to live with housing insecurity — it’s terrifying. You stop sleeping at night. It feels like a massive rejection by the community you worked so hard to support. You’re spoken about like a beggar, or even worse — ‘Not in my back yard’ — as though the people who serve you in restaurants or treat you in the clinic when you’re sick are not worthy of living in your community.

“I know what this community is capable of. I know its history. There is creativity and brilliance here,” Duncan said through tears. “I live in my dream community, but after the holidays I strongly suspect I will need to tender my resignation at the clinic, abandon my post, and leave Provincetown.”

Dana Masterpolo, chair of the planning board, asked the town’s leaders to have courage. “Not everything is popular, but it’s time to try something,” she said.

Michael Gaucher said that Hawaii, Palm Springs, and New Orleans have all put short-term rental restrictions in place, and he asked the town to place a moratorium on new short-term rentals. He also asked the select board to consider a zoning map to define where short-term rentals are allowed and for a new rule that 50 percent of all newly constructed units be deed-restricted to prohibit short-term rentals.

Seth Ohrn said that, as the new manager at Spindler’s restaurant, he was shocked to discover that J-1 students in Provincetown were “living in nothing short of squalor.

“These kids should not be sleeping on mattresses on the floor, with broken windows and no screens,” Ohrn said. No one is checking on the conditions in these rentals, he added.

“These kids are working three jobs per person, 5 a.m. to midnight,” said Ohrn. “They should have somewhere to go that’s not a mattress on the floor.”

Laura Silber, a housing planner for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, said that she and Tucker Holland, the housing director for Nantucket, “wanted to offer our resources and our partnership as you guys work through this.

“We have just undertaken a short-term rental study, an evaluation to look at putting restrictions in place,” said Silber. “I’m really curious to see where you guys head with this, and we’d be happy to share information.”

Building an Agenda

After hearing the public’s comments, the three boards got to work trying to build an agenda for town meeting. The warrant will need to be finalized early in March, said Town Manager Alex Morse, so time is already running short.

“I’m grateful to the select board and the town manager for finally taking housing by the horns,” said Cass Benson, a member of the Year-Round Rental Housing Trust. “I feel like the housing committees need stronger taskmasters. We’re just groups of people that show up once a month.

“There’s been this void in housing for 10 or 20 years now,” Benson continued. “We need more help — like a housing czar.”

At the end of the meeting, Morse listed several areas for further work, including a deed restriction program, short-term rental regulations, and a housing production goal. Select board member Leslie Sandberg added improvements to bus and shuttle services to the list, and board member Louise Venden said the town should use its bylaws to make evicting tenants to make way for condos much more difficult.

With that much on the agenda, time could be the most limited resource. Morse told the select board last week that if not everything is ready by March it would still be possible to call a special town meeting later in the spring or summer.

Planning Board Rethinks Employee Housing Article

Article 8 will be amended or withdrawn on town meeting floor

PROVINCETOWN — Only a week after the Nov. 9 special town meeting warrant was finalized, the planning board decided that Article 8, which would add employee housing to the town’s inclusionary zoning bylaw, needs a major overhaul. Without it, the new rule could inadvertently hinder affordable ownership, the members concluded.

The board discussed pulling the article entirely at its Oct. 13 meeting, but because that isn’t possible it will go forward with a Nov. 3 public hearing on the proposal and see if an amendment can be developed for town meeting floor.

The problem was discovered in a routine meeting between town staff and planning board Chair Dana Masterpolo. The staff had drafted Article 8 to encourage private sector developers to create workforce and seasonal housing, especially since the town itself has no money earmarked for that purpose, Assistant Town Manager David Gardner told the Independent.

Provincetown’s existing inclusionary bylaw — which uses carrots and sticks to persuade developers to include ownership properties in their projects — would be expanded under Article 8 to also offer those same incentives to projects that include employee housing.

Initially, Gardner told the planning board that, with this change, developers would likely continue to build affordable ownership units because their interest is almost always in selling their newly built units, not in running rental housing. Meanwhile, the idea was that local business owners would become more likely to build employee housing units because incentives like height or setback waivers could make some marginal projects pencil out.

The planning board had unanimously supported the measure.

At last week’s meeting, however, Masterpolo asked what might stop a developer of ownership units from choosing employee housing instead, accepting the deed restriction from town hall, and selling those units to local businesses.

Given the definitions in the bylaw, nothing would prevent that, and such units would almost certainly sell for more than the affordable ownership units that inclusionary zoning is designed to create. Without any changes, Article 8 could bring the town’s affordable ownership efforts to a halt, which was not the intent of its drafters, both Gardner and Masterpolo said.

Masterpolo said the board would try to write an amendment at its workshop on Nov. 3 that could save the measure.

“If they’re gaining access to the incentives at the same rate — 20 percent of the project’s floor area — and worker housing has fewer restrictions, they’ll always build worker housing,” Gardner said. “I still think it’s a good idea to have employee housing in the bylaw, but what is the exact rate where they both work? We should be able to find that.”

In addition to changing the percentage at which employee units can trigger incentives, Masterpolo said that the definition of employee housing needs more work.

“When something becomes an affordable unit, it goes under the purview of the town, it’s regulated, there’s a process for it,” Masterpolo said. “With this new amendment, we want to make sure that what we’re putting in place has some meaning and some boundaries to it that serve the overall goal.”

The town’s zoning bylaw currently defines “employee housing” as being living quarters for unrelated individuals on a seasonal or year-round basis and for more than one month. There are no income or owner-occupancy rules, and the clearest restriction is against short-term rentals.

“When you dive into the details, there really are some things we need to figure out,” Masterpolo said.

LOOK WEST

Housing Solutions From Around the Country

The Cape Cod Commission features ideas from Vail, Tahoe, and Boston

HARWICH PORT — Leaders from across the Cape gathered to discuss the region’s most pressing problems — above all, the housing crisis — at the Cape Cod Commission’s annual conference on Aug. 1 and 2.

“We’re seeing restaurants and retail places that are closed two to three days a week now because they can’t get employees,” said Dan Wolf, founder of Cape Air and former state senator for the Cape and Islands. “Every employer in here, municipal or private sector, is having trouble, and housing is the fulcrum.

“When a hurricane goes through, you don’t say, maybe we’ll fix that in 10 years,” Wolf added. “The challenge is to deal with this as a crisis, and not business as usual.”

Wolf’s remarks were followed by three speakers from off Cape who were invited to share their housing success stories with local leadership. The housing director of Vail, Colo., a county planner from North Lake Tahoe, Calif., and a housing design leader from Boston all spoke in turn about strategies that are working in their communities.

George Ruther, Vail’s housing director, told the group that in 2017 Vail formally resolved to acquire 1,000 new deed restrictions on residential units in town. The deed restrictions do not restrict the sale price of the property, the income of the person living there, or who may own the property. Instead, the restriction specifies that the person who lives there, whether owner or renter, must be working 30 hours a week or more in Eagle County, Colo.

“In 2017, we had about 5,300 year-round residents and 7,200 dwelling units,” said Ruther. “Those 5,300 residents lived in about 1,800 free-market dwelling units and 688 deed-restricted units. The other 4,800 dwellings sat vacant for the majority of the year.

“We didn’t have land,” Ruther added. Vail is “99 percent built out” and surrounded by National Forest land on all sides. “We do have a lot of dwelling units,” he said. “We needed to figure out a way to get folks living in the homes that we had within town. In my way of looking at things, we don’t have a housing problem, we have an occupancy problem in our community.”

In the last five years, Vail has paid $11.6 million for 169 deed restrictions in 87 separate transactions. The average cost per deed restriction has been $68,500, and the average cost per square foot was $82. Many of the early deed restrictions were in larger projects, but starting in 2019 the town bought 62 separate deed restrictions on condo, duplex, and townhome units.

Colorado municipalities “live and die by sales taxes,” Ruther said, and last fall the town voted for a half-percent sales tax increase dedicated specifically to housing. The proposal passed with 54 percent of the vote.

The town’s housing authority recently began buying homes outright, placing deed restrictions on them, and then immediately reselling them. “With the all-cash buyers that were coming to the table, we had residents that were willing and capable of purchasing, but they weren’t afforded time to compete,” said Ruther. “So, the Vail InDEED program stepped in.”

Devin McNally is a planner in Placer County, Calif., which runs from the northern suburbs of Sacramento up to the ski towns of North Lake Tahoe. “Similar to Cape Cod,” McNally said, “we have had a major problem with our housing stock being used for purposes other than housing.

“We call this our second-home culture,” said McNally. “In the North Lake Tahoe region, 64 percent of our homes sit vacant most of the year.” Meanwhile, two-thirds of the working population was commuting into the region from places as far away as Reno and Sacramento.

McNally said the county first created a deed restriction it calls “achievable housing” and then took multiple approaches to getting units into that “second market” of deed-restricted homes. At first, only local workers with certain incomes could live in them, but after several changes to the formula, Placer County now allows any local worker to live in the deed-restricted units.

Many programs nationwide are restricted to first-time buyers, but Placer County discarded that restriction as well. “This allows our school district and hospital district to hire — to say, sell your home wherever you live, and we can help you get a new one here,” said McNally.

Condo conversions and many kinds of new construction are now required to be 50 percent achievable units. The county has also published detailed design standards so that projects can get much faster by-right approvals — including eight free and preapproved plans for accessory dwelling units and a dedicated staffer to help people through the process.

“We were averaging one or two ADU applications per year,” said McNally. “Now we get over 100 applications per year.