WELLFLEET — Helen Miranda Wilson, the new owner of the house at 177 Peace Valley Road, outlined for the historical commission on July 9 her reasons for concluding that the only course forward is to demolish the dilapidated 19th-century structure rather than restore it.

Under the town’s demolition delay bylaw, tearing down any structure more than 75 years old requires a review by the historical commission.

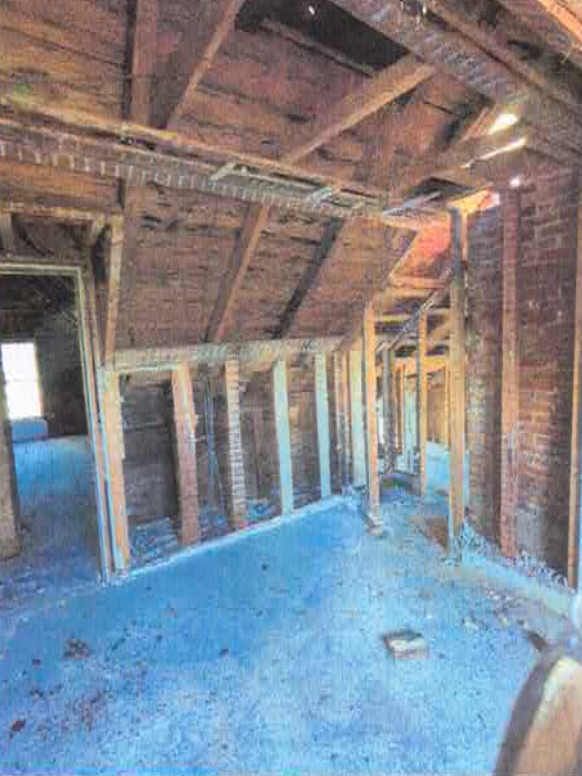

The foundation was crumbling, the floors were rotted, and the interior was infested with mold after years of exposure to the elements, said Wilson, who provided the commission with a structural engineer’s report.

But after an hour-long and at times prickly public hearing, the panel unanimously voted to impose an 18-month demolition delay on the property to allow time for alternatives to be explored.

In a July 14 phone interview, Wilson argued that none of the commissioners had gone inside the house to see its current condition — something she pointed out several times during the public hearing. “You have to go inside and eyeball it,” Wilson said. “My rationale for demolition was based on what you could see and match up with the structural engineer’s report.”

Wilson emailed Building Commissioner Justin Post on July 14, asking that he inspect the building’s interior. The house has significantly deteriorated since the town condemned it in 2018, Wilson said. The building commissioner has the authority to order demolition if he determines that the structure is a public safety hazard.

The house on Peace Valley Road is well known to townspeople as it is visible from Route 6. It was originally a Cape-style home built around 1850. A second house was brought from South Wellfleet and added to the original in about 1880 along with some Victorian elements.

After several decades of neglect under its longtime previous owner, Robert Bonds of Boston, local health officials condemned the house seven years ago for violations of state codes. The town then enrolled the property in a state program meant to help communities bring such houses back to livable condition.

The Mass. attorney general’s office, which oversees the program, tried working with Bonds, but after having no success, initiated the process of placing the house in receivership.

At a hearing in Southeast Housing Court on May 21, the judge approved a “motion for leave to sell.” The sale by Bonds to Wilson for $900,000 closed on May 22. Despite the change in ownership, the property continues to be enrolled in the attorney general’s program. A housing court judge has set a hearing for Aug. 12 to discuss Wilson’s plans for the house.

Historical commission co-chair Timothy Curley-Egan told the group that the town’s attorney had checked with the attorney general’s office and was told the agency would abide by whatever decision the local historical commission made, whether it was to allow demolition or institute a delay.

Wilson told the commission that three different builders had gone through the house in addition to the structural engineer. All concluded that it would have to be lifted so that the foundation could be replaced.

“The mold issue is what kind of broke the camel’s back for me,” Wilson said, adding that remediation would likely require the use of strong chemicals.

Commissioner Kevin Sheehan questioned Wilson’s plan to raze the house, commenting that at previous hearings, when the property was still owned by Bonds, “you were adamant about saving this property by any means necessary.

“Yet now that you’ve purchased it, you want to demolish it,” Sheehan said. “I’m concerned, to say the least, that you’ve completely changed your tune.”

Wilson countered that she had said, at earlier hearings, that she hoped the property got the attention it deserved. Noting that she had not been inside the house since 2010, and a great deal of deterioration had occurred since then, she said, “I haven’t changed my tune, I’ve gotten more information.”

Wilson’s structural engineer, Michele Cudilo, noted in her report that runoff water had penetrated the basement, and fissures in the foundation had caused walls to bulge. Cudilo said the structure required complete replacement of the foundation and first-floor framing. The second floor had areas of mold in the timber framing, and the joists were rotted through in some places.

“The number of repair components warrants consideration of a full building replacement due to numerous poor and substandard conditions,” Cudilo wrote in her conclusion.

Russell Frank, a licensed architect who was recently appointed to the historical commission but had not yet been sworn in, offered comments but did not participate in any votes. This “doesn’t seem like it is a required demolition, based on what the report says,” Frank said. Lifting a house off the foundation to install a new one is not unusual on Cape Cod, he added, and should not be considered a substantial obstacle to taking “the right path” and saving the house.

In April, David Freed, an architect hired by Bonds, told the commission that the house could be preserved without any demolition. While Freed based the assessment on laser imagery of the interior, since he had not himself been inside the house, commission co-chair David Kornetsky noted at the July 9 hearing, “I guess the question is, does this suggest that there should be further exploration about whether the house could be potentially saved?”

Wilson told the Independent she had several options in mind when she purchased the property, including its full demolition with no new construction, which has now become her preferred outcome. She said she wants to subdivide the land and donate the wetland portion to the conservation commission while retaining ownership of the uplands.

“It never resolves,” she says. “It continues. Every year there are budget problems, and this year, there is dealing with the structure, which needs to be revamped. But it’s always ongoing.”

“It never resolves,” she says. “It continues. Every year there are budget problems, and this year, there is dealing with the structure, which needs to be revamped. But it’s always ongoing.”