Communities across the state — and on the Outer Cape — are beginning mandatory testing of their public water supplies for PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), a group of compounds that are believed to be harmful to people’s health.

Under standards recently finalized by the state Dept. of Environmental Protection (DEP), levels of six PFAS compounds in drinking water may not exceed 20 parts per trillion. There are no enforceable federal standards.

What Is PFAS?

PFAS compounds, which are known as “forever chemicals” because they never completely degrade, date back to the 1950s. They are used in nonstick cookware, grease-resistant food packaging, outdoor clothing, stain-resistant carpeting, ski wax, and other everyday items.

PFAS compounds have recently been found in the containers of mosquito-control products, which can leach into the pesticide itself. PFAS was detected in Anvil 10 + 10, a product used for aerial and ground spraying of mosquitoes to combat eastern equine encephalitis.

According to the Mass. DEP website, studies indicate that sufficiently elevated levels of PFAS will have harmful effects on fetuses and infants, the thyroid, liver, kidneys, certain hormones, and the immune system. Some studies also link PFAS to cancer.

The Silent Spring Institute, an environmental organization that has extensively researched the compounds, was the first to find PFAS in some Cape Cod wells in 2009, according to Laurel Schaider, a senior scientist at the institute. “We tested 101 wells in 12 Cape towns,” Schaider said. “Nearly half had at least one PFAS chemical. But, broadly speaking, we found the vast majority of the wells did not exceed the standard.”

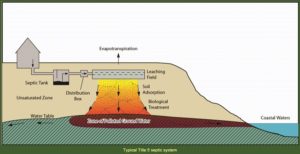

One possible source may be septic systems. “The wells with higher levels of nitrate had PFAS,” she said.

Military Sources

About 400 military bases nationwide, including Joint Base Cape Cod on the Upper Cape, have contaminated the soil and groundwater in their regions with PFAS compounds. In Mashpee, two municipal wells are currently off-line due to the presence of PFAS linked to the base. Expensive carbon filters have been installed, and operations manager Andy Marks said he sampled the municipal wells for PFAS on April 1 under the new state standard. Results are not yet available. “Our fingers are crossed,” he said.

Firefighting foam is also a source of PFAS and has affected the Barnstable water system with contamination from the firefighting training academy in that town.

Mass. Takes the Lead

Massachusetts is one of a handful of states to set limits for PFAS.

The new state regulations require testing for six compounds, referred to as PFAS6. Remedial actions must be taken when levels of one compound or combinations exceed 20 parts per trillion.

Public water suppliers serving 50,000 or more were required to conduct initial tests beginning Jan. 1. The requirement kicked in for medium water suppliers of over 10,000 on April 1. Small public water suppliers of 10,000 or less must start Oct. 1.

Testing requirements are not limited to municipal water suppliers. Systems that supply workplaces or housing developments must also be tested. In the fall, non-community water systems, such as those in restaurants, motels, campgrounds, and golf courses, will be required to test for elevated PFAS levels.

Outer Cape Plans

Eastham has already done its first round of testing under the state’s new standard, according to Town Administrator Jacqueline Beebe. No detectable amounts of the compounds were found in the town’s two wells, based on samples drawn at the end of January.

Provincetown Water Supt. Cody Salisbury plans to test its municipal system, which also serves North Truro, sometime this month. All 11 active wells at three locations in Truro will be tested, Salisbury said, as well as two emergency supply wells, not in use, on the former U.S. Air Force training base.

“We did a voluntary test sampling in late 2019 and early 2020,” Salisbury said of the system. “That was for 70 parts per trillion, and there was no detection. You never know at the new test level, but we’re not anticipating problems.”

Since more than 60 percent of Truro is served by private wells, the state will work with local officials to do a sampling across town as part of a process that’s still rolling out. “All towns that meet the criteria will be contacted in the near future about participating in the program,” said DEP spokesman Edmund Coletta in an email.

In Wellfleet, Rebekah Eldridge, the water dept. clerk, said Whitewater Inc., the company that operates the town’s water system, emailed that it was working with the DEP, but had not yet received answers to its questions from the agency. Since it is a small water system, testing won’t be required until October.

For public water suppliers, testing is required for four consecutive quarters and must be done in the first month of each quarter. Detection of PFAS in a public water supply triggers a second sampling to confirm initial findings. If the level confirmed is above 10 parts per trillion, the system must be tested monthly. If the average of monthly testing over a quarter exceeds 20 ppt, the water provider must take action, including taking the source offline or treating the water.

Sole Source Aquifer

Because Cape Cod is a glacial deposit, with no clay layers or areas of bedrock, it’s categorized as having a “sole source aquifer,” leading residents to fear that groundwater contamination, such as PFAS found on the Upper Cape or in Barnstable, can migrate to the Outer Cape.

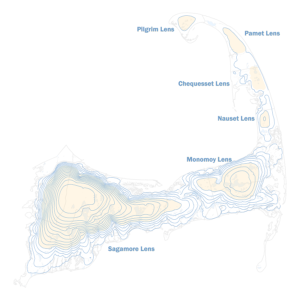

But Tim Pasakarnis, the Cape Cod Commission’s water resource analyst, says that’s just not possible. The Cape’s aquifer is actually made up of six individual lenses of groundwater separated by hydrological features such as rivers, Pasakarnis explained. At the center of each lens is a mound, where the groundwater is highest. The groundwater flows out from those high points into the dividing rivers and marshes.

“Between the Sagamore and the Monomoy lens is the Bass River dividing it,” Pasakarnis said. “Between the Pamet and Chequessett lens is the Pamet River. The groundwater flows into the divide from the high points of the lenses on either side.” To migrate from the Outer or Mid Cape to the Upper Cape, “the groundwater would have to cross those divides and go uphill,” Pasakarnis added.

Further Testing

Silent Spring Institute is involved in three testing programs on the Cape measuring PFAS in drinking water and in the residents themselves. As part of the STEEP program, done in collaboration with the University of Rhode Island, Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the state Dept. of Public Health, Silent Spring will be doing additional testing of private wells this summer.

Under a program called PFAS-REACH, Silent Spring will look at exposure to PFAS and effects on preschool-age children, using blood tests and questionnaires filled out by parents. “We’ll look at effects on the immune system in Hyannis and Pease Trade Port, N.H.,” said Schaider. The latter is the site of the former Pease Air Force Base in Portsmouth.

Silent Spring is also part of a multistate study of PFAS coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry. “We will be collecting blood and urine samples,” said Schaider. “We will have a clinic on Hyannis Main Street. We’ll do body measurements and have questionnaires about where people lived.” Children ages 4 to 17 will be part of the study, she said.