One story surfacing this Thanksgiving tells of a search party from the Mayflower, anchored in Provincetown Harbor, raiding a gravesite near Corn Hill in Truro. About 10 bushels of corn and beans were found by the party and brought to their hungry shipmates.

As a descendant of those hungry shipmates, I’m grateful they found nourishment and survived. I have a sense of their desperation and the relief the buried harvest must have brought. But clearly this land was inhabited by an organized people who had stored part of their life-sustaining crops. This was someone else’s food.

History is full of invasions and land grabs by powerful adventurers and colonizers. Yet our national narrative continues to characterize the Mayflower passengers as people on a high-minded quest to bring democracy to a barren land, not looters and thieves of precious winter stores. Real history is complicated.

Another story going around this year is about what happened in 1970. How did Wamsutta Frank James wake up non-native people by not delivering a speech before a prestigious group assembled to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the arrival of the Mayflower in Cape Cod Bay?

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts invited schoolteacher Frank James, the beloved leader of the Nauset Regional High School band and orchestra, to address a Boston banquet as a representative of the Indians. Mr. James, as I knew him in school, told the Cape Codder that, on receiving the invitation, he wrote a speech and was asked to submit it to be checked for grammar and spelling for a press release about the event.

James was told his speech was “too inflammatory” and would make people uncomfortable. He was provided an alternate speech. Someone from the State House drove to James’s house in Chatham, where they spent hours attempting to reconcile the two speeches, the one James wrote with the one state officials wanted him to read. He decided to withdraw from the event.

The headline in the Codder read “Wampanoag Skips 350th Banquet; Won’t Speak With Forked Tongue.” A substitute Indian was found to address the banquet. He wore a Sioux-Dakota war bonnet.

James’s speech was published in full in the Cape Codder. It began:

I speak to you as a man — a Wampanoag man. I am a proud man, proud of my ancestry, my accomplishments won by a strict parental direction (“You must succeed — your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community”).

And it continued:

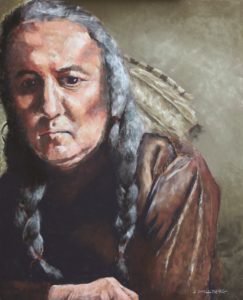

History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal…. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it….

High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, stands the statue of our great Sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We, the descendants of this great Sachem, have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man caused us to be silent.

Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts…. Our spirit refuses to die.

When James wrote his speech, a 19-month occupation had begun of the old prison on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay by the American Indian Movement.

I have no doubt that the Indians have had things right about challenging the U.S. history of imperialism, enslavement, and all those broken treaties. Right to call U.S. policies and practices toward the Indians nothing less than genocide. And they’ve been right about living in sacred harmony with the natural world.

Frank James reminded us with his speech about honor, about building trustworthy relationships, and about the heart-sickening betrayals by the U.S. government that still continue.

Scholars like Daniel J. Silverman and Ian Saxine have studied who the Wampanoag were and how they responded to the English who anchored first in Provincetown Harbor. This past summer, the Eastham Public Library and the Eastham 400 Commemoration Committee (eastham400.org) organized a full season of virtual sunset and campfire stories, shared by local residents: Mayflower and Wampanoag descendants and others. These interviews can be viewed still.

After the undelivered speech was published, Frank James and his tribal colleagues met on Cole’s Hill above Plymouth Rock. There, he read his speech and they declared Thanksgiving to be a National Day of Mourning.

The National Day of Mourning has continued every Thanksgiving for 50 years as both a sacred and a very political event. It is preceded by fasting from sundown the day before. The mourning will continue until mutual respect and real equity are all of ours to share.