In Donald Beal’s Provincetown studio, in the rear of his Alden Street home, a large painting of two women leaving the water hangs on a central wall. After working on it for a year and a half, he says it is finished. He soon qualifies his statement: “I hope it is finished.”

Beal’s paintings often take on a life of their own. “I’m trying to get to where the picture wants to go. That can take a while,” he says. Beal’s former teacher at Parsons, Paul Resika, instilled in him the principle to “follow the paint.”

“Each mark suggests the next mark, which suggests the next mark, and so things appear and disappear,” says Beal. “I’ve had paintings go from landscapes to florals to interiors to dogs to people to landscape to florals,” he says. His latest painting, Bathers, Dogs, and Squall, is no exception.

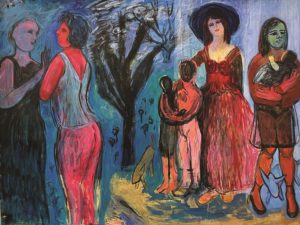

In the painting, Beal depicts the two women and two dogs in a rocky landscape with the sea stretching into the distance. Dark clouds and a group of three leaning trees dramatize the scene. The central character, stepping forward in a dark red bathing suit, is the protagonist of the painting. She is sturdy and serene, an anchor amidst the shifting light and impending storm. She also grounded the painting throughout its making. “I painted her out around a dozen times,” says Beal. “But the painting kept insisting that she come back.”

Beal compiled images of the painting in its different stages over the last year and a half for a short video. There were constants: the reappearing central figure and certain compositional ideas, like the concave shape of the foreground and the juxtaposition of strong horizontals and verticals. But aside from that, elements moved in and out of the painting at a brisk pace: other figures appeared and disappeared, the weather changed, towels and dogs moved throughout the composition, and the topography shifted from a sandy pond to a rocky coast. There are at least a handful of good paintings buried under the final skin. “Sometimes you must kill your darlings,” says Beal. He approaches a painting like someone on a specific quest.

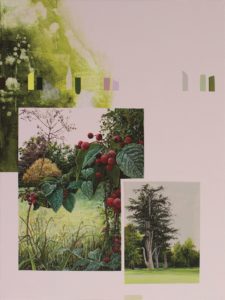

Part of what Beal is looking for is a sense of formal harmony. In this painting, he was searching for “a strong sense of light” and a composition that felt solid. But there were more intangible pursuits — things he describes as “bubbling up” through the formal problems, like “getting the central bather’s attitude right.” About another painting, a lush picture of green foliage and flowers, Beal was searching for the “right rhythm so it didn’t feel mannered or decorative.”

Ultimately, he hopes the paintings “start to have this other life where it isn’t just a painting but seems to project something that’s more than.” He’s ready to let Bathers, Dogs, and Squall sit because “everything there is working in concert to make this thing feel like it’s transcendent,” he says. “It transcends its material, its subject.”

Beal’s work recalls ancient Greek and Roman art in its concerns with beauty, harmony, and transcendence. Some of the imagery also hearkens to antiquity, most notably the bather, a recurring figure in his work. She conveys a timelessness and an ideal of beauty, and like Greek and Roman sculpture, she feels simultaneously ethereal and grounded in the world. On Beal’s studio wall is an older work, a multifigure plaster relief influenced by Roman sarcophagi. Here the figures seem engaged in a battle. “Antiquity is at the root of so much that we do,” says Beal, who mentions Ovid as his go-to bedtime reading. “This art is impossibly beautiful, and it explores the full range and complexity of being human,” he says.

Along with beauty, Beal mentions dynamism as a quality he admires in classical art — an affinity evident in his ongoing series based on Provincetown’s Beech Forest. In his studio, he has a few paintings from this body of work; tangled branches match the intensity of any battle scene. He began painting in the Beech Forest in the early 1990s, and although he still paints outdoors, most of the recent work for his upcoming exhibition was developed in the studio, where he works from memory and smaller works done in the landscape.

Beal, who grew up in Westford, first arrived in Provincetown in the fall of 1982 as a graduate student at Parsons. At the time, the school ran a program where students could live and work in Provincetown for a semester. He rented a place in the West End for $125 a month and had a studio at the Art Association. Initially, “it didn’t register as being a place for me,” says Beal. “I had my sights on New York.” During that time, however, he met Khristine Hopkins, now his wife and a librarian at the Provincetown library, and by 1985 he was living in Provincetown.

“I had soured on New York,” says Beal. “I also just suddenly woke up to the place. I saw how strange and beautiful it was, and how important the landscape could be to me as a painter.”

“I started off making all the paintings everybody makes here: the harbor, the boats, the big open vistas,” says Beal. “I had nothing meaningful to add to it. I just had a lot of easy answers.” It wasn’t until he discovered the Beech Forest that he found his place in the local landscape. “I realized this is a place where there were no easy answers,” he says. “It changed my whole idea of pictorial space because of the trees and things coming in from all edges of your plane of vision.”

A recent painting from this body of work, Fallen Tree and Wetland, was the first piece Beal did after suffering a serious concussion on a construction site. (Beal returned to taking on construction jobs and working as a personal trainer after teaching at UMass Dartmouth for 17 years). For months after the accident, he couldn’t paint as he waited for his vision to recover.

Like many of his paintings, Fallen Tree and Wetland is painted on a panel, a surface that allows for an expansive lexicon of painterly moves. Some areas are built up with thick, impasto paint; other areas are wiped down, leaving ghostly traces of paint. There’s a dynamism in the paint application and also in the imagery of a white tree fallen amidst a cascade of other branches. One of his friends referred to the painting as a map of Beal’s neural synapses. It seems to resound with some of the trauma of his injury, which happened around the time of the Covid shutdown.

“I’m sure it came out of the anxiety between the brain injury and being shut off from everybody,” says Beal. But like the recurring figure of the bather (“I’m not sure what that’s about,” he says), this image didn’t begin with a concept or an idea; rather, it bubbled to the surface through a struggle of trying to make things work visually.

“I never think about it,” says Beal in reference to any obvious metaphor between the painting and his injury. “When you work, it just shows up on its own. I’m happy to not think about it. When I think about it, it feels forced and kind of silly.”

Into the Woods

The event: An exhibition of recent paintings by Donald Beal

The time: June 16 through July 9; opening reception Friday, June 16, 5 to 7 p.m.

The place: Berta Walker Gallery, 208 Bradford St, Provincetown

The cost: Free