Charles Ayling, whose wealthy family owned homes in Chestnut Hill and Centerville, was 27 when he decided he would “experiment with something that had been talked about and seen occasionally: that was the horseless carriage.” In the spring of 1902, he purchased a bright red Stanley Steamer, designed by the Stanley twins, Francis and Freelan, who lived in Newton, one town over from Ayling’s hometown.

Ayling and his friend William Butler frequently took the Stanley Steamer to Cape Cod from Boston on weekends, a journey that took 10 to 12 hours each way. On one such trip, they decided, on a Saturday morning, to drive from Centerville to Provincetown — a trip that would set a new record. The farthest a car had traveled on Cape Cod in 1902 was Orleans.

The newfangled steam-powered vehicle was less than eight feet long and was steered with a long tiller rather than a steering wheel. The smooth tires were similar to those on bicycles. It was equipped with a passenger seat that was located over the engine and in front of the driver. “I had seen one or two of them floundering by and chugging along as it were,” Ayling later said in an oral history made in 1958. “They were not popular because it made all the horses shy and run,” he said.

At the turn of the 20th century, travel over land was mostly done by horse-drawn coaches or by train. Ayling’s grandfather, John Cornish, who had been a sea captain delivering goods along the East Coast, purchased a stagecoach business when he retired. His coaches conveyed passengers from Centerville to Sandwich, where they could connect with the Boston route.

Ayling said that transportation was in his grandfather’s blood, and that he must have inherited it.

Before he made his purchase, Ayling’s sole experience in driving a Stanley Steamer was his short spin around the perimeter of the car sales lot. He then drove the vehicle home.

“Being one of the younger members of the Chestnut Hill society, they all said, ‘Well, that young Charlie is really going crazy,’ ” Ayling said. “ ‘He’s just gone and bought one of those funny horseless things, and he’s even building a little building to put it in.’ ”

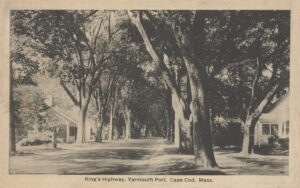

For the trip, “We loaded up with some provisions, an extra can of gasoline and started for Provincetown,” Ayling said. He and Butler set off at dawn, taking Route 6A, known at that time as Old King’s Highway — this was decades before Route 6 would be constructed.

Stanley Steamers required a great deal of water to run, so the pair of adventurers stopped “at every little watering trough in the town’s villages” to fill the boiler. At the time, there were only about 600 cars on the road in the entire state of Massachusetts, so the bright red car attracted crowds of townspeople along their route. Some would come close enough to touch the car, while others were afraid to approach it.

Whenever the Stanley Steamer encountered horses, Ayling would bring the car to a halt. Butler would jump out and hold the beasts by their reins, while the car passed. The horses, spooked by the chugging of the car, were frequently difficult to hold onto. “I’m afraid we were responsible for one or two runaways,” said Ayling.

While roads through the Mid- and Lower Cape were well constructed by 1902, traveling became slow and difficult as they proceeded along the sandy Outer Cape. It’s not that Provincetown was off the map at that point, but the ease in getting to it by steamship, ferry, or train meant roads weren’t a priority out this far. Outer Cape roads were essentially cart paths with ruts 8 to 10 inches deep. There were times when the car would get mired in the sand, in which case one or both men had to get out and push.

The Steamer’s boiler was designed with a plug that would blow out if the pressure got too high. As the vehicle labored up one sandy hill in North Truro, the plug blew and went right through a nearby wooden fence. “I’m glad it didn’t hit anybody that was standing around,” Ayling said.

He and Butler were road trip veterans, thanks to their frequent runs from Boston to the Cape. Punctured tires were common and had to be patched on the road. They were therefore well prepared for the necessary tire repairs during the trip to the Cape’s tip.

When the Stanley Steamer reached downtown Provincetown at about 5 p.m., a crowd of 100 or more people were there to greet the travelers: word had preceded them that they were on the way. Onlookers were all “yelling and screaming, looking and laughing,” and it was generally creating quite a spectacle, Ayling said. The group followed the car as it slowly drove through town.

Some accounts say the town crier led the way, clanging his bell. One version, in Blue-Water Men and Other Cape Codders, written by Katharine Crosby in 1946, said the town crier rang his bell to alert people “to this strange ungodly sight,” but that was not his main purpose. “He felt the need of keeping the street clear of horses and teams so no damage would be done — he was without a doubt the Cape’s first traffic officer,” wrote Crosby.

One last obstacle stood between the travelers and the Gifford House, where they would stay overnight: a steep hill. While onlookers were doubtful the car could make it, Ayling was confident. “I could go up a hill very quickly for a short distance, and I did,” Ayling said. “I can look back now and see the people staring at me going up that hill in a cloud of steam.”

But when Ayling tried to register at the Gifford House, the proprietor asked if he owned “the funny thing outside.” When Ayling said he did, the man told him he couldn’t stay at the hotel with the car parked out front because it might explode and set fire to the hotel. Ayling had to stow the car a fair distance away, in a barn that sat in the middle of a field.

On Sunday, Ayling and Butler set off to find gasoline for the return trip to Centerville. Gas stations did not yet exist. They waited outside the local drugstore until it opened at 11 a.m.

They needed several gallons, but the proprietor, after checking the cellar, “brought up this rusty old can, and he had a little less than a gallon.” Ayling paid 75 cents for the gasoline and continued his search for more.

He was directed to a local painter who used gas for removing paint. Ayling went to the painter’s house but had to wait for him to return from church. The painter sold him three quarts for 75 cents. “So, I took all the gasoline that there was in Provincetown for $1.50,” said Ayling.

The gallon and a half proved enough to power the Stanley Steamer to Centerville with about a pint to spare. Ayling and Butler were exhausted from their adventure, “but the trip was accomplished, and the record was made, so we had a very lovely time,” Ayling said. According to local history, Ayling’s record stood for about a year.

The Tales of Cape Cod, a nonprofit organization founded in Barnstable in 1949 to record oral histories, provided the Independent with a transcription of a taped interview with Ayling, making the source of this story Ayling’s own recollections. Reports of Ayling’s trip sometimes place it in 1901, but Ayling referred to 1902 in his account.