PROVINCETOWN — The Center for Coastal Studies is losing $200,000 in federal funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that supports aerial surveys of right whale activity in the Gulf of Maine in the fall.

The organization’s regular aerial surveys, which take place in the late winter and spring over Cape Cod Bay, are still set to go forward as usual — although the Trump administration has proposed a 27-percent cut to NOAA’s budget for the fiscal year that begins in October.

Appropriations subcommittees in the U.S. House and Senate have pushed back on that proposal, introducing bills of their own that would keep the agency level-funded or impose much smaller cuts.

In the meantime, the Center for Coastal Studies is assessing its vulnerability.

“In the face of budget uncertainty, and to ensure that we maintain all our research efforts, such as those focused on protecting this vulnerable population, we have, for some time, been diversifying our funding sources,” said the Center’s Executive Director Anne-Marie Runfola in a written statement.

That includes an increasing reliance on foundation grants, individual donors, and state and local contracts, according to the Center’s Communications Director Douglas Karlson.

“We continue to find strong support from those who live, work, and visit the Cape and Islands, because they understand all too well the value of protecting our precious ocean and coastal environment,” Runfola wrote.

In the 2023-2024 season, the Center for Coastal Studies conducted 37 aerial surveys covering more than 12,000 nautical miles, according to the organization’s annual report.

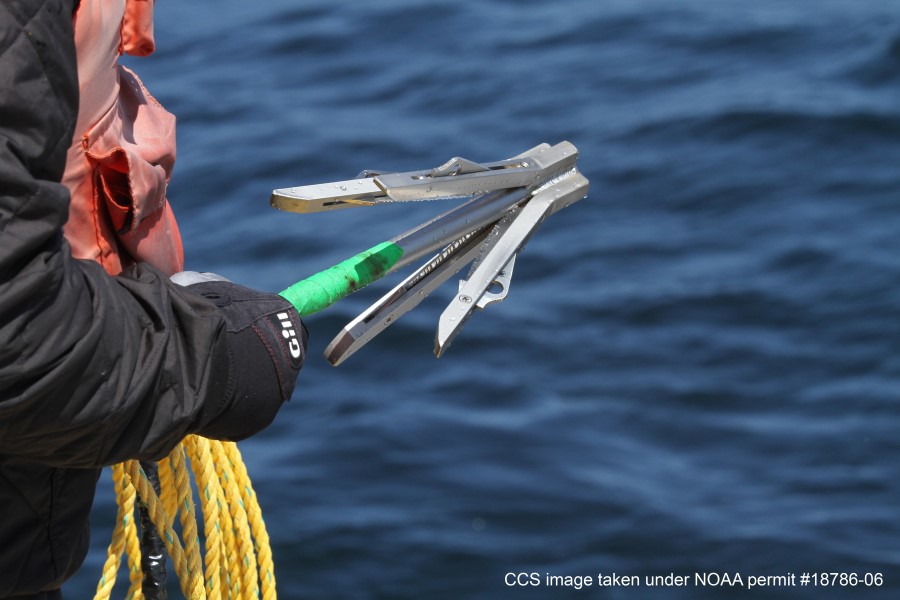

Along with marine expeditions that scoop zooplankton samples from the bay’s surface, the aerial surveys form the “backbone” of the organization’s data collection on the disappearing species, the report says. There are believed to be about 372 North Atlantic right whales remaining, only about 70 of which are females of reproductive age.

Almost half the population of North Atlantic right whales was in Cape Cod Bay this past April, according to a press release from the Center.

“In recent years we’ve recognized the importance of extending our research into the greater Gulf of Maine in the fall, when North Atlantic right whales are present there,” wrote Daniel Palacios, director of the center’s right whale ecology program, in a statement. Data on the fall movements of whales “could greatly expand our knowledge and understanding of right whale behavior, and how best to protect them,” Palacios wrote.

The fall flights had been taking place for several years and had “expanded both the temporal and geographic scope of our monitoring, helping us assess how environmental changes in the Gulf of Maine may influence the distribution of North Atlantic right whales,” Karlson wrote.

The winter and spring aerial surveying program in Cape Cod Bay is funded through a three-year grant, although that award is also subject to annual appropriations, Karlson said. Given the threats to NOAA’s budget, that funding could potentially be in danger — although the written statement from the Center says that “our core research and surveillance operations in Cape Cod Bay during winter and spring will continue without interruption.”

The CCS is one of several nonprofits on the Outer Cape that are feeling the first impacts of federal cuts. WOMR, the Outer Cape’s community radio station, is set to lose almost 20 percent of its annual revenue following the defunding of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting in July. TestNTreat, the sexual health program at Outer Cape Health Services, was notified of a 10-percent state funding cut in anticipation of broader cuts to public health programs in May, and the AIDS Support Group of Cape Cod is expecting cuts as well.