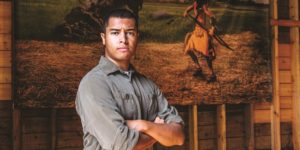

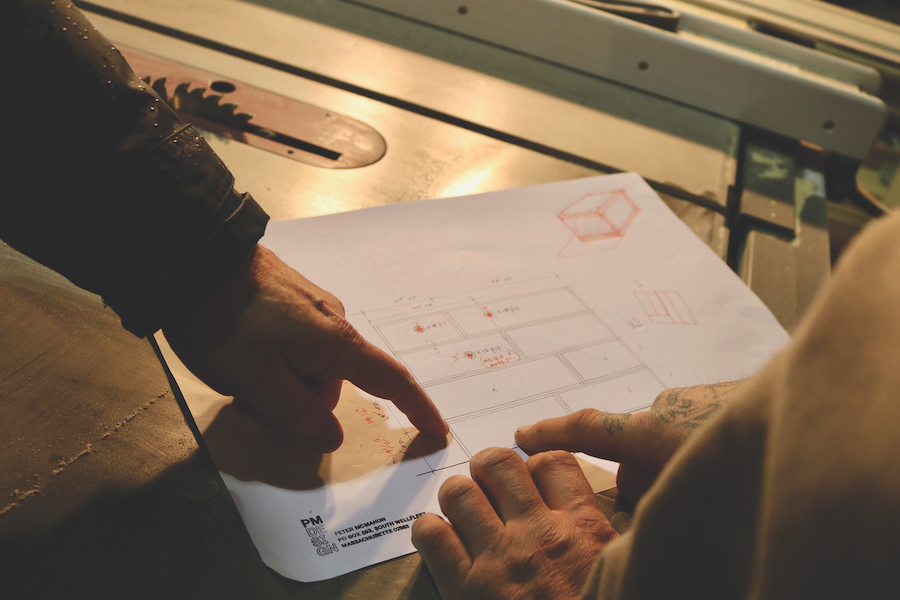

Peter McMahon is not going to brag about his tables. They are what he calls “a Flintstones solution” to a practical problem. After McMahon founded the Cape Cod Modern House Trust in 2007 to restore and preserve the endangered modern houses — often derelict — that were hidden in the woods of Wellfleet, he realized he’d need to furnish them. He was no “fine woodworker,” he says, but he knew his way around steel and wood. “I wanted to make a really strong table in the fewest possible moves.”

McMahon’s tables are sleek, uncomplicated, and deceptively light. Their form follows function. These are Y tables: he borrowed the design for the legs from the French architect Jean Prouvé: a Y-shape, perfectly splayed so that they’re not in anybody’s way. “It can’t be improved upon,” says McMahon. He tried a competing design: “The X tables didn’t really work.”

Steel brackets of his own design attach the legs to a center beam and to the tabletop. The result is a piece of furniture so strong that, McMahon says, “You could have two people jumping up and down on it, and it wouldn’t break.”

His ideas about building things are, he says, probably thanks to Froebel blocks — those simple cubes, cones, arches, and cylinders invented in the mid-1800s by the German educator Friedrich Froebel, who also invented kindergarten. Children of the 1970s in small-town Massachusetts played with them, or versions of them, too. His mother bought the ones made by Creative Playthings. “All these famous architects had them,” says McMahon. “Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius.”

McMahon’s block-building years were spent in an old house in Reading decorated with his mother’s collection of farmhouse furniture. She was an art historian but was also interested in Scandinavian design, and she brought home pieces from a trip to Denmark. McMahon, thoroughly inspired by the shapes around him, went to Boston Architectural College in the 1980s.

His design philosophy isn’t just modernist — it’s utilitarian. “Beauty isn’t something added, like a decoration. Beauty comes from structure,” he says. “This gets me to Vitruvius.” Vitruvius was a Roman architect and engineer who lived in the first century B.C.E. and is known for his multi-volume work titled De Architectura. His three requirements of good design, says McMahon, were commodity, firmness, and delight.

What Vitruvius really meant, says McMahon, is “utility, strength, and beauty.” A well-designed thing has to suit its purpose. “The modernists would say that if it’s useful and sound, then it’s probably beautiful.”

The Y table’s design is always the same. But depending on what purpose the table must serve, McMahon employs different materials in the construction. The tabletop might be made of solid wood, plywood, or rough boards. The leg materials vary as well. The “basic cheapo leg” is made of a piece of framing lumber, not sculpted. McMahon handles the loose legs as if they were Froebel blocks. “You’d use this on a temporary table,” he says of the “cheapo” leg. “A quick and dirty table.”

Legs that are a step up are made of knotty pine or Douglas fir — also framing lumber, but this time sculpted, with rounded edges. Even nicer are those made of clear Douglas fir, free of knots. The fanciest legs are made of ash, the same wood that baseball bats are made of and rounded on both sides, says McMahon. “Like someone’s calf.”

McMahon uses regular steel fasteners for indoor tables and stainless steel for outdoor ones. At first, he used the same enamel-painted steel brackets, made by the steel fabricator New England Welding, for both indoor and outdoor versions. But the steel in the outdoor tables rusted when exposed to the salt air. So, McMahon went back to the fabricator for brackets in high alloy stainless steel, painted with enamel. “Even if the paint falls off, it’ll never rust,” he says. The indoor brackets are blue and the outdoor ones orange so he can easily tell them apart.

One of the tables can be seen at the Kohlberg house on a bluff south of Newcomb Hollow. Because this one’s a “high visibility table,” says McMahon, its Douglas fir top rests on sculpted ash legs. Blue brackets peek out from underneath. Through the glass sliding doors that lead to the porch overlooking the ocean, another table can be seen: an outdoor version, the top made with three 2-by-10 planks and the legs of unsculpted fir.

When considering material for his tables, McMahon doesn’t just think of the appearance of the wood; he considers the activities and accoutrements that the table will support. Coffee cups will leak, pens will press and glide, heavy dishes will heat and stick, elbows will rest. That’s the “commodity” element, he says. “It has to be suited for its function.”

In the Baroque era, carving and decoration might give a piece of furniture the appearance of luxury. When modernists wanted luxury, they changed their material.

“The fanciest table I ever made,” McMahon says. was topped with clear Alaskan cedar, “but it was the exact same design.”