BOURNE — For 90 years, the two arched bridges connecting the mainland to Cape Cod have served as a welcome sight to visitors heading for seaside stays and year-round residents making their way back home.

The Depression-era lanes seem narrow to drivers of today’s SUVs. More important, the structures are showing serious wear.

“Existing and potential maintenance issues” are a major concern for the business community, said Paul Niedzwiecki, CEO of the Cape Cod Chamber of Commerce. “If they are not replaced in five years, one bridge would have to be closed.”

Niedzwiecki was referring to a study done by the Army Corps of Engineers in 2020, which concluded that the two bridges, if not replaced, would require a major overhaul expected to cost about $350 million. Each would need to be closed for up to two years while that work was done — a factor that led to the recommendation that the bridges instead be replaced.

Kristy Senatori, executive director of the Cape Cod Commission, agreed. “It’s not a question of whether we should replace these structures but how,” she wrote in an email to the Independent. “New bridges, built in a manner that is in the best interest of the region, are critical to the long-term vitality of Cape Cod.”

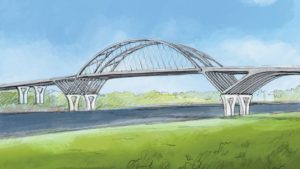

Planning is still in the early stages, with the most recent step taken at a public forum last month: the unveiling of three potential designs.

One offers an updated version of the existing arches. A second design brings to mind the Zakim Bridge that leads north from Boston to Charlestown and Interstate 93; it features cables fanning out from tall pylons to support the bridge deck. The third design is a concrete box girder, with none of the metalwork seen on the existing bridges.

That last one “looks like a big concrete thruway that you might find in Key West,” Wendy Northcross, former executive director of the Cape’s Chamber of Commerce, told the Independent last week.

Whatever design is ultimately selected, decision makers at the Mass. Dept. of Transportation (MassDOT) are looking at twin bridges at both the Sagamore and Bourne crossings — not just during construction but for the long haul.

At each location, if a two-bridge design is chosen, construction would proceed like this: While the first new bridge is being built, two-way traffic would continue on the existing bridge. Two-way traffic would then shift to the first new bridge and the old bridge would be demolished. Then the second new bridge would be built. When both are finished, one bridge would be dedicated to traffic coming onto the Cape and the second to leaving.

“There are great advantages to that because you really wouldn’t have to disrupt the traffic flow over the canal during construction,” Northcross said.

Project planners believe two bridges would also prove more efficient than a single bridge. Each bridge would have two travel lanes and a third lane for turning onto exits flanking the bridge, based on the current design. Lane configurations will be discussed in greater detail at future public forums.

Canal History

Plimoth Colony traders discussed the need for a canal connecting Buzzards Bay with Cape Cod Bay starting in 1620, according to a history of the canal found at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers New England District website. In those days, Dutch trading ships would sail north from New York and enter the Scusset River from Cape Cod Bay. The ships would then be portaged over land for several miles and resume sailing on the Manomet River, which flows into Buzzards Bay.

In 1776, George Washington saw the strategic advantage of a canal and ordered Thomas Machin, an engineer in the Continental Army, to look into its feasibility. Machin recommended in his report, believed to be the first Cape Cod canal survey, that a new waterway be constructed.

Several surveys would follow over the next 125 years, but each time the scope of the project and its projected costs proved too daunting.

In 1904, businessman August Belmont became interested in the canal project. He purchased the Boston, Cape Cod and New York Canal Company, which held a charter for canal construction, and hired well-known engineer William Barclay Parsons. Based on a study by Parsons, Belmont decided to build the canal, beginning the work in 1909.

Dredging began at both ends with crews working toward the middle.

The Buzzards Bay Railroad Bridge was completed in 1910, the original Bourne Bridge in 1911, and the Sagamore in 1913. Each bridge had two cantilevered spans that opened to let boat traffic through. Belmont opened the canal in 1914, charging tolls to ships passing through. Work on making the channel deeper continued through 1916.

President Woodrow Wilson ordered the Federal Railroad Administration to take over canal operations during World War I, after a German submarine fired on an American tugboat off the coast of Nauset Beach. After the war, Belmont resumed operation of the canal until 1927 when he sold it to the federal government for $11.5 million.

Congress placed the bridges under the authority of the Army Corps of Engineers, the toll was eliminated, and plans for massive improvements were made. The 17.4-mile-long canal was widened and deepened. It was the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 that funded the Bourne and Sagamore bridges that connect the Cape to the mainland today.

“In accordance with Public Works Administration regulations, work was distributed widely; and whenever practical, hand labor was used instead of machinery to provide as many jobs as possible,” according to the Army Corps history. The budget was $4.6 million, and the Corps estimates the project employed 700 people. The bridges were completed in 1935.

After overseeing the canal since 1930, the Army Corps in 2020 agreed to turn ownership and maintenance of bridges over to the MassDOT once the current bridge-building project is complete.

A Funding Snafu

U.S. Rep. William Keating has called the bridge rebuilding “critical.” But funding it is an ongoing challenge. According to the State House News Service, Transportation Secretary Jamey Tesler said the Army Corps expects inflation to push the cost to between $3 billion and $4 billion.

The search for federal grants is ongoing. In May, the Army Corps and MassDOT applied for $1.1 billion under the federal Multimodal Project Discretionary Grant Program and in August for $1.89 billion from the Bridge Investment Program.

Keating said the agencies learned from those applications. The first was not selected for the current funding round. The second may not be either, said the congressman.

One problem was apparently that the agencies used 2026 as the date work would start. State officials have since told Keating they would change the start date to 2024. “That will make it much more competitive,” the congressman said.

Many of the grants also require matching funds — something neither the Army Corps nor MassDOT had prepared for, Keating said. Those will be lined up for future grant applications.

Niedzwiecki is a member of a newly formed Canal Bridges Task Force. He said the group’s purpose is to “align support for the bridge project.” Representatives from three agencies sit on it: The Cape Cod Commission’s role is planning, he said, while the Chamber’s role is figuring in the economics of the region. The third agency, the Association to Preserve Cape Cod, will look out for effects on the environment.

While businesspeople are concerned about traffic disruptions when work begins, they also know the job has to be done, said Niedzwiecki.

Two identical virtual public information meetings are planned: at 6 p.m. on Jan. 24 and Jan. 26, 2023. The meetings will be hosted at mass.gov/massdot-highway-design-public-hearings.

Those looking to leave a comment should go to mass.gov/cape-bridges and follow the link to “your opinion matters.”