TRURO — Last winter’s nor’easters, blasting the Outer Cape coastline with icy winds and churning surf, further carved away the dunes at Ballston Beach that had already been eroding at a rate of about three feet a year for decades. The storms left one house teetering on the edge of the bluff. That house, and its septic tank, were eventually moved.

But as storms scoured the beach below, remnants of a bygone era — when summer cottages lined the bluffs that are now underwater — have come into view.

Pipes poke out of the dunes above the beach while, nearby, a long red cable snakes along the sand. Slabs of peat, likely from the Pamet River salt marshes that sat far back from the shore 150 years ago, and massive rectangles of concrete litter the beach at low tide. At high tide, woe to the unsuspecting swimmers where cement blocks lurk below the surface.

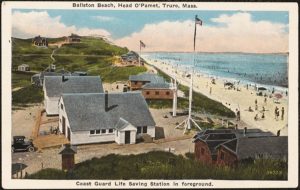

One concrete square is lined with brick. Could it have been the base of the chimney from the lifesaving station that was built on the bluff in 1872?

During a recent walk on the beach with Dan Sanders and Nicola Moore, longtime Truro residents and frequent beachcombers, Sanders said he thinks the cable could have once been part of a telegraph line running from the Pamet Life-Saving Service’s station to the Cahoon Hollow station a few miles to the south. Sanders notes that there are posts in view along the beach that may have held it.

Communication among the network of life-saving stations dotting the Outer Cape coastline until the 1930s was essential during emergencies, when violent storms drove ships onto the sandbars off the coast, where they foundered.

One of the most well-known wrecks not far from the Pamet station was of the English ship Jason in December 1893. The U.S. Coast Guard describes it as “one of the most appalling disasters that has ever taken place on the shores of Cape Cod, with 26 lives being lost.” The ship went down about a half mile north of what is now Ballston Beach, and only the ship’s apprentice survived.

Sanders believes the large concrete slabs on the beach are most likely all that’s left of a popular cottage colony. The cottages sat on cement slabs, and the pipes that still pierce the dune probably ran from those cottages.

For more than a half century, families settled in at the cottages built by New York businessman Sheldon Ball and his wife, Lucy, from whom the beach got its name. The Balls fell in love with the coast of Truro and its sweeping views of the Atlantic Ocean and purchased more than 1,000 feet of oceanfront property in 1889. A few years later, they opened Ballston Beach Bungalows, which was run by Sheldon and his son, S. Osborne “Ossie” Ball.

In the days before the widespread ownership of automobiles, those who arrived for the summer had limited options here. They came to swim, sunbathe, and socialize with their neighbors. Summer folk would congregate in the Balls’ large dining pavilion for meals and in their ballroom for entertainment in the evening.

“There was a piano they could play, and everyone would sing along,” Sanders said. “And they could tell stories.”

The cottages had no electricity initially, and bathroom facilities consisted of outhouses.

There was also a bowling alley, which was taken down in 1914 to make room for more cottages.

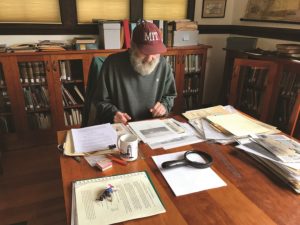

Norman Pope is considered one of the local experts on Ballston, although he didn’t arrive in Truro until the 1970s. By that time, the Ball cottages were gone and the land was owned by the National Park Service. In a recent interview at the Truro Historical Society’s Cobb Archive, Pope talked about what was then a strict class separation between the year-rounders and summer residents.

“The locals were the chambermaids,” he said. “They were not allowed to mingle with Mr. Ball’s guests.”

Many guests stayed for the entire season. “He advertised in New York newspapers to have a clientele with the money to do it,” Pope said. “Even then, the Hamptons were crowded.”

The late James G. Whitelaw, whose family had lived on Ballston Beach since the 1880s and who died in 2018, had firsthand knowledge of living next door to the bungalows. In a recorded presentation in 2009, given at the Truro library as part of its “One Book/One Town” series, Whitelaw described Ossie as “an interesting neighbor: he believed in happy hour.”

Whitelaw, born in 1930, didn’t know Ossie’s father, Sheldon Ball, who died of a heart attack in 1923 while walking on Ballston Beach. His impression of the cottage colony next door to his home was that it was best to pretty much leave the guests there in peace. “There were locals and the summer people,” he said, “and nobody in between.”

Whitelaw recalled that, as a kid, he would earn a nickel a night pulling crabgrass out of the lawns of the seasonal homeowners.

The area also had the Pamet Valley Golf Course from about 1906 to the 1920s, and it was popular among Ball’s summer guests. Whitelaw said a friend described it to him as “nine holes and 900 mosquitos.”

“It was tees and greens, and, in the middle, watch out,” he said.

While his guests loved Ball, it was a different story when it came to the local population, Whitelaw said. Ball put up a fence around the perimeter of his cottage colony, including the beach area, which made night-riding in a dune buggy a dangerous pastime. He posted the compound with “private property” signs. Whitelaw recalled that, when he had his own children, “They were told not to go on the mean man’s property.”

Others recall Ball, who lived and had a law practice in Provincetown, as affable and somewhat eccentric. Nicola Moore, whose family has a house on South Pamet Road, said the colony was gone by the time she was a teenager, but she remembers when the shacks were filled with guests.

“The thing that impressed me the most about the cottages was that they had iceboxes instead of refrigerators, so the iceman cameth,” she said in an email. “The cottages were musty and small and perfect in every way as far as I remember.”

The Balls’ cottages were moved back several times over the years to avoid going over the bluff.

The National Park Service purchased the Ball property in 1967 for $290,000, according to a newspaper announcement on file at the Highland House Museum. The agency allowed the summer tenants to continue renting them until 1970, according to local histories, when they were either demolished or moved off the property.