Alexandra Marshall was just 26 when her husband, Tim Buxton, normally joyous and enthusiastic in the face of challenges, committed suicide. It was 1970 and the couple was in Ghana on a volunteer mission.

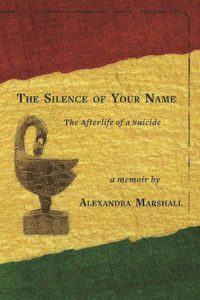

Like many survivors, Marshall endured haunting questions and feelings of guilt. Her memoir, The Silence of Your Name: The Afterlife of a Suicide, released on Nov. 7 by Arrowsmith Press, tells the story of Buxton’s death and how Marshall survived as a young widow.

They were typical children of the socially conscious and politically active 1960s. Buxton had marched for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery, while Marshall spent a year traveling through Asia and Africa. They married in 1966, and a few years later moved to New Hampshire, where Buxton was a well-liked faculty member at Phillips Exeter Academy and Marshall taught French in the public schools.

After a visit from the founder of Operation Crossroads Africa in 1970, Marshall was inspired to lead a volunteer group of college students to Ghana that summer. “I did have to kind of talk Tim into wanting to do it,” Marshall says in an interview at her home in Wellfleet. “I did not realize at all, until I read his journals after his death, how apprehensive he was even while we were still in New Hampshire.”

While Marshall had traveled through Africa, Buxton’s overseas experiences were limited to Western Europe. Three days after they landed in Ghana, he was hospitalized with a high fever. Doctors assumed it was malaria despite the disease’s normal 7-to-30-day incubation period. He was given anti-malarial drugs and sedatives but remained dehydrated and sleep deprived. Entries in Buxton’s journal, read later by Marshall, spoke of his “mind racing until it seems to want to burst.”

Buxton was discharged from the hospital, and he went with Marshall to recuperate at the home of Jean, a Canadian teacher, and his wife, Helene. But less than 48 hours later — on day 10 of their trip — Marshall was awakened by Jean, who had found Buxton on the floor of the shower room. He had slit his throat with a bread knife. Marshall jumped on the back of Jean’s motorcycle and they raced to get a doctor, but Buxton died shortly after the doctor arrived.

“I accused myself of cowardice for not protecting Tim from himself in the first place,” Marshall writes in her memoir, “and then, failing that, for not holding his bloody head in my lap for the rest of his life.” Marshall was left with a question that would plague her for years: had the high fever and drugs affected her husband’s brain?

Buxton was cremated, but the ceremony was different from what Marshall expected. Following Hindu ritual, his body was placed on a large pyre that was lit by Marshall’s father, who had come to Ghana to help with the arrangements. His ashes were shipped back to be buried in a family plot. Buxton’s mother never acknowledged her son’s suicide, insisting he died of malaria. Marshall initially accepted this, calling it “the upside of denial,” as it relieved some of her guilt.

Barbara Sproul, Buxton’s friend, and her then-boyfriend, the novelist Philip Roth, invited Marshall to stay in a cabin in Woodstock, N.Y. near their farmhouse. “They’d absorbed me into their life,” Marshall says. Roth introduced her to contemporary American literature, and she became a prolific reader. Marshall realized through watching Roth that she, too, “had a story to tell.”

In the years that followed, Marshall wrote several novels that helped her heal. Though inexperienced at writing, she applied her years of dance training under choreographer Martha Graham. “In dance, literally one motion leads to another motion,” she says. “That’s the way the body works. And, ideally, that’s the way it works with writing. One sentence moves into another sentence because it’s a continuation.”

Marshall’s first novel, for which Roth suggested the title The Child Widow, was loosely autobiographical. It would remain unpublished and be rewritten several times in the ensuing decades. Marshall wrote a second novel, also never published. Then, in 1977, her third novel, Gus in Bronze, was picked up by Alfred A. Knopf. Written soon after the death of her mother, the book is about a mother of three who is dying of cancer. Her daughter requests that a bronze head be sculpted to remember her mother.

In one scene, the husband, Andreas, falls asleep in a cot beside his wife’s bed, missing the moment of her death. “In creating Andreas,” writes Marshall in her memoir, “I gave myself the occasion to feel less alone in, and less guilty for, my having fallen asleep the night Tim took a knife to his throat.”

Marshall met fellow writer James Carroll, a former Catholic priest, through her literary agent while she was writing the nonfiction book Still Waters, based on her year-long observation of a New England beaver pond. They married in 1977 and had a daughter, Elizabeth, and son, Patrick. Four years after Patrick’s birth, Marshall discovered she was pregnant despite a tubal ligation. The delighted family prepared for a June birth. But in late April, Marshall felt contractions and stopped at her doctor’s office in Boston. The receptionist sent her on her way without an examination, saying it was a false alarm.

Marshall returned to the family vacation home in Pocasset and soon realized the baby was indeed on the way. Carroll drove her to a small nearby hospital with no neonatal intensive care unit. “Our baby lived her entire life in the delivery room, where Jim held her in his arms and looked into her open eyes as he baptized her,” writes Marshall.

It wasn’t until 2000 — 30 years after her first husband’s death — that Marshall returned to Ghana and visited the house where Tim had died. “It was as if the terrible event that had taken place in that shower cubicle had passed into the realm of legend,” she writes, “which almost made me feel as if I were no longer held to blame. Or maybe never had been.”

When Marshall returned home, she tried again to write The Child Widow without success. She decided to turn to memoir rather than fiction after Buxton’s mother died. Her son was not mentioned in the obituary. The title The Silence of Your Name refers to “what happens with a suicide if it’s not spoken about,” Marshall says.

“The thing I’ve learned is that all losses are connected,” Marshall continues. “My losses are connected to each other, but also connected to your losses. If I understood that when I was younger, it would have made me feel less lonely.”