PLYMOUTH — The Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station has been shut down, but the arguments over what to do with its highly radioactive spent fuel are heating up.

A Navajo activist from New Mexico delivered a powerful warning on Monday about a plan to create a giant nuclear waste storage facility there, calling it an act of environmental racism.

“I want you to know, we are watching you in New Mexico,” Leona Morgan told a citizens panel on the decommissioning of the Plymouth reactor. “Your waste will not come to New Mexico if we can help it.”

In its 47 years of operation, the Pilgrim Station generated hundreds of tons of spent fuel, which is now being loaded into 61 massive steel and cement casks that will sit on a concrete pad off Rocky Hill Road in Plymouth. Holtec International, the company that purchased Pilgrim shortly after it shut down in May 2019, is securing a license for its HI-STORE Consolidated Interim Storage facility, proposed for Lea County in southeastern New Mexico. Waste from plants all over the country would be sent there.

Company officials have said the spent fuel at Pilgrim and other plants it has purchased would be shipped to New Mexico and stored underground until a permanent federal repository is built.

Morgan told the Nuclear Decommissioning Citizens Advisory Panel during Monday’s Zoom meeting that the governor of New Mexico, state land commissioner, and attorney general all oppose Holtec’s plan, along with many residents statewide. New Mexico has already been overburdened by the effects of uranium mining, she said.

“When you people say, ‘Take it away,’ that means bringing it to our communities, which to me is the most blatant form of environmental racism,” Morgan said. “This is beyond unjust. It’s something that will impact future generations, and not just residents here but all along the transportation routes.”

The initial license from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) for the interim storage facility would be for 40 years, with an option to renew for 40 more. Holtec’s plan calls for initially taking 500 canisters of spent nuclear fuel, about 8,600 metric tons. In phases, the facility would ultimately accept 10,000 canisters.

Currently, nuclear plants nationwide have produced about 85,000 metric tons of waste, which is being stored at 80 sites in 35 states. Meanwhile, plans for a permanent federal repository at Yucca Mountain in Nevada have stalled for decades due to determined opposition.

John McKirgan, chief of storage and transportation for the licensing branch of the NRC, attended the Monday meeting to answer questions. His agency develops design standards for packaging spent fuel. The Dept. of Energy will handle issues related to shipping. “They have to notify the states, tribes, and local law enforcement prior to shipments,” McKirgan said.

The NRC is considering an application for a separate site in West Texas, proposed by Interim Storage Partners LLC. Completion of a safety review there is expected in May. Holtec’s completion date is being delayed so the company can answer further questions.

The NRC review includes soil analysis, flooding hazards, “aircraft crash hazards,” building design, and “aging management analysis.” The environmental review of both interim storage facilities should be completed by July.

“Technically, the NRC could issue the license this year,” said Holtec spokesman Patrick O’Brien in an email, and the interim facility could begin operation in 2024.

Sheltering in Place

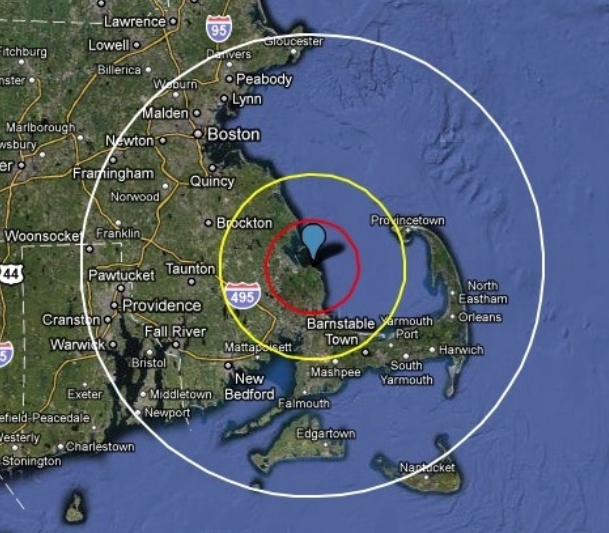

When the Pilgrim reactor shut down, residents on both sides of the Sagamore Bridge breathed a collective sigh of relief. And for good reason: the tip of Provincetown is just 19 miles across the bay from the problem-plagued plant, which sits on the coast of southern Plymouth.

“There’s no escape from the Cape,” was a frequent comment about a possible accident. The state’s emergency plans called for holding the 250,000 Cape residents back from the bridges until Plymouth and other towns close to the plant had been evacuated. Cape residents were advised to “shelter in place” in their homes.

People remain concerned about the 4,000 radioactive spent fuel assemblies.

The dilemma of what to do with spent fuel is a tough one, said Susan Weegar, a Wellfleet resident and member of the Down Cape Downwinders. “I’m totally of two minds,” Weegar said. “It seems to be unsafe to be leaving it in Plymouth, where it is on the seacoast, but the idea of putting it in transport and shipping it across the country is such a nightmare.”

The federal Government Accountability Office has characterized spent fuel as one of the most hazardous substances created by humans, with some of its components remaining radioactive for tens of thousands of years.

Provincetown resident Brian O’Malley, a retired physician, called any plan for long-term storage of the radioactive fuel in Plymouth “preposterous.”

“I don’t know what the right path is, but the issue with nuclear power is the waste,” he said. “We shouldn’t be making it anymore.”

Dry Cask Concerns

The casks being used to store Pilgrim’s spent fuel are called HI-STORM 100s, manufactured by Holtec. Each cask consists of a stainless-steel inner canister where the fuel assemblies are stored, surrounded by inert gas. About 27 inches of concrete is installed between that inner canister and the carbon-steel outer shell to act as a radiation shield. When loaded, each 18-foot-high cask weighs 150 tons.

Holtec boasts that its casks could withstand the impact of a Boeing 767 traveling at 350 miles per hour, as well as extreme natural events like tornadoes, but opponents ask whether the casks are vulnerable to modern missiles launched by terrorists. They also argue that the inner canisters, about a half inch thick, are too thin and could corrode in the salt air.

Holtec officials have said the design, material, and workmanship of the dry casks have a 25-year warranty. That number is not reassuring, said Pilgrim Watch president Mary Lampert, who sits on the Nuclear Decommissioning Citizens Advisory Panel.

“Holtec provided a 25-year warranty for manufacturing defects, period,” Lampert said. “Even they were not willing to have a lengthy guarantee, so why should we believe the casks can withstand time?”

There is also concern about potential leaks. Holtec has said that leaking casks could not be opened. Instead, a separate larger cask would be slipped over the leaking cask, Russian-doll style.

“If they leak, what will that do to the bay?” asked Wellfleet resident Judith Kwiat Cumbler. “It’s horrible for fish and horrible for those of us who live on the bay. It is truly alarming how much radiation is in those things.”

McKirgan said Monday that the casks will be inspected for signs of degradation and corrosion, but Lampert countered that the program calls for sampling a few rather than all. According to the NRC official, technical assumptions about the rest of the casks could be made from the random sampling.

Divided Opinions

While activists agreed on the need to shut down Pilgrim, they differ on what to do with the waste.

Lampert believes it should be moved out of Plymouth. The environmental justice argument is an “oversimplification” of the issue, she said.

“Plymouth is unsuited for extended spent fuel storage, period,” Lampert said. “It is densely populated, an appealing terrorist target, and its marine environment conducive to corroding the casks.”

Diane Turco of Cape Downwinders disagrees. “We do not want it moved to New Mexico,” she said, noting the region’s population is predominantly Hispanic. Projects like this are often located in poorer communities, she said.

The governor of New Mexico, the All Pueblo Council, and citizens’ groups have all voiced opposition, she said.

“We want it safe and secure right here,” Turco continued. “It needs to be in better casks, not cheap Holtec canisters.” Turco also called for more robust security of the fuel storage area.

Lampert argued that the sparser population and arid conditions at the New Mexico target site make it preferable to Plymouth.

“There always will be opponents,” Lampert said. “But if the site makes sense, then, like with the Quabbin Reservoir, the greater good prevails. But those directly harmed should be recompensed.”

Holtec’s application for its HI-STORE facility already faces four separate appeals, according to Kevin Kamp, a nuclear expert from the national group Beyond Nuclear. His organization filed an appeal representing some abutters. Appeals were also filed by the Sierra Club, among others.