TRURO — Since purchasing their beachfront property at 42 Great Hollow Road in 2018, Susan and Wesley Chapman have sent out an annual email inviting their neighbors to be guests on the private beach in front of their house each summer.

While it may seem like a generous gesture, that’s not how Richard Anders and Judith Paprin, or Ellen Carno, who live on Obbo Drive, behind the Chapmans, see it.

Their houses have no beach frontage, but they believe that their membership in a neighborhood association established a decade ago gives them the right to use the Chapmans’ beach whenever they want. To them, the Chapmans’ email message seemed more like a notice that the beach was private, with neighbors allowed by invitation only.

This neighborhood in North Truro for decades consisted of a handful of lots with small rental cottages under one owner. But over the last 10 years, the owner has sold off the lots as prime real estate. The new neighbors and their lawyers are now debating in state Land Court over who gets to use the beach.

Visitors to Massachusetts are often surprised to see “no trespassing” and “private beach” signs posted in front of waterfront houses. In every other coastal state, property owners’ rights end at the mean high tide line. But in Massachusetts, ownership of the intertidal zone, between the mean high and low tide lines, can be privately held.

The archaic laws creating this situation date back to the 1640s, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony expanded private property rights to encourage waterfront development. The public right of access in the intertidal zone is limited to fishing, fowling, and navigation.

Only the strongest of swimmers should venture into water between the high and low tide mark if the beach is private, since courts have ruled that one’s feet may not touch the sand beneath.

More than 70 percent of the Massachusetts coastline is privately owned, according to state statistics.

In the Land Court case filed on Dec. 1, both sides agree that the Chapmans own the beach in front of their property. What plaintiffs Anders, Paprin, and Carno are seeking is affirmation of their right to use that beach, along with a court order preventing the Chapmans from interfering with their right to do so.

The case comes down to differing interpretations of the documents related to the Sunset Acres Beach Association, to which all three property owners belong. The plaintiffs’ Boston attorney, Diane Tillotson, contends that the association, established in 2010 by developer Joseph Obert, allows all its members use of the beach that is part of the property later purchased by the Chapmans.

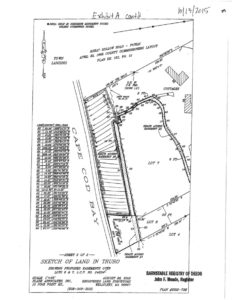

The arrangement was accomplished through a series of easements, Tillotson says. One of those easements includes the beach area in front of the Chapmans’ property. The association also has a set of beach rules and regulations that strengthen the neighbors’ claim to the beach, Tillotson says.

But the Chapmans say the easement cited in the documents is limited to a 10-foot-wide path between the front of their lawn and the beach. Susan Chapman said in a phone interview that both Obert and the real estate broker told her in 2018 that the beach the association members have the right to use is a stretch to the south of her beach.

Association members can’t access that common beach directly because it’s at the bottom of a steep coastal bank, she said, and that’s why the easements across her property had been created.

The paths are clearly marked in crushed white shells, Chapman said.

Chapman said she had asked Obert about the use of her beach by association members prior to buying the property. “Joe said, ‘You know, I usually just invite them to sit on my beach,’ ” Chapman said.

Chapman has kept up her annual email invite to the neighbors. This past summer, she included a map of her property with the easements marked on it. She crossed out the beach, to indicate that the easement was limited to the 10-foot path.

Wellfleet attorney Bruce Bierhans, who represents the Chapmans, told the Independent that he plans to argue “the appropriate document had never been recorded regarding the use of the beach.”

The issue won’t be resolved quickly. Bierhans said cases like this one can take two years or more for final disposition.

Attorney Tillotson did not respond to a request for comment for this story. Anders declined to comment.

Susan Chapman hopes the case will finally settle the beach dispute. “For our benefit, we want the rights clarified as well,” she said.