PROVINCETOWN — A 21-year-old North Atlantic right whale known as Porcia was observed in Cape Cod Bay on March 18. The whale was seen swimming with her 2023 calf by her side. And last week, before this first mother-calf pair of the season was spotted, Scott Landry, director of the disentanglement team at the Center for Coastal Studies, estimated there were already between 30 and 40 right whales in the bay.

That means Cape Cod lobstermen are on land, waiting out the whales.

Elsewhere in Massachusetts waters, however, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is running an experiment that gives lobster fishermen exempted fishing permits to work in areas that are otherwise restricted. What they are testing is something called on-demand fishing gear — gear operated via an app to minimize the time that lengths of rope stay in the water.

Landry wants to see “our absolute reliance on rope to harvest our food” go away. But for the time being Cape Cod Bay is not the site of any on-demand gear experiments.

Lobsterman Mike Rego, who lives in Truro, is glad about the cautious approach. He sees the strict closures, though they shorten his season, as too important. “I don’t want to lose four months of my fishing season, but I don’t want to kill a whale either,” he said. “The whales are protected while they’re here. Why jeopardize any of that?”

The North Atlantic right whale is a critically endangered species with only some 340 animals remaining in the world. The majority of those whales feed in Cape Cod Bay during their thousand-mile spring migration from their calving grounds off the coasts of Georgia and Florida to Canada, where they summer.

The greatest threats to the right whales’ survival are vessel strikes and entanglement in fishing rope. As the Independent has reported, five of 30 entanglements in Cape Cod Bay reported to the CCS last year involved right whales.

The state’s Div. of Marine Fisheries and NOAA have already restricted speeds in the bay to 10 knots for vessels 65 or more feet long. And Cape Cod lobstermen are required to keep their gear — traps managed with ropes — out of the water. The fishery is restricted from Feb. 1 until May 15, according to the DMF. The restriction can last longer if the whales linger here.

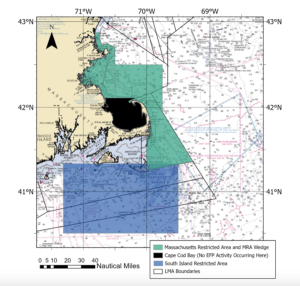

The on-demand gear trials are underway in two locations: the Massachusetts restricted area, which stretches from Newburyport south to Nantucket, and the South Island restricted area, off the southern coast of Martha’s Vineyard. There are five participating vessels in each area.

According to Henry Milliken, the supervisory research biologist at NOAA and principal investigator overseeing the gear trial, its purpose is twofold: to familiarize lobster fishermen with the gear and to provide feedback to the manufacturers whose gear is being tested.

Although this is the first time the gear is being used in closed waters, fishermen have been working with it for four years, Milliken said. And the technology is improving. The Boston Globe reported that in 2020, on-demand traps were retrieved successfully 74 percent of the time. Now, Milliken said, the traps are successful more than 90 percent of the time. That’s because the manufacturers have been incorporating feedback into the development of their gear, he said.

The gear falls into three categories: buoyant spool (which unfurls on command), inflatable lift bag (the only truly ropeless adaptation), and pop-up buoy (where a buoy line is released on command), each of which is triggered by a signal from fishermen.

While data suggest that the trial is going well, support for on-demand gear is far from unanimous among lobstermen.

“I think it’s a Star Wars idea that will not work,” said Dana Pazolt, a Truro-based lobsterman who sets his traps on the bay side in the fall and on the ocean side in the spring and summer. Pazolt’s 800 lobster traps have 50 miles of rope.

One concern about removing the ropes, Pazolt said, is the potential for the traps to be snagged in other fishing gear. Without the ropes to mark his trap locations, he said, “How does a dragger or a scalloper know where they are?”

“You mark your gear for a lot of different reasons,” Landry said. “Not only so you can retrieve it, but the other issue is to let your neighbors know my gear is here. In New England, where we have many different types of fisheries overlapping with each other, that is a massive issue.”

Traps with vertical lines have state-based marking requirements depending on the fisherman’s main port or permit. Massachusetts mandates that traps have at least four sets of red and green marks, the top set being a total of four feet long and within 12 feet of the water’s surface.

Milliken said those traditional markings could eventually be replaced by Trap Tracker or a similar app for mapping and retrieving traps. But he also admitted that trial participants are “fishing in areas where the overlap with other fishermen is less likely.”

The trials prove on-demand gear can work under perfect conditions, Pazolt said. The trouble is, he said, “It’s not a perfect world.”

To Rego, who works with CCS scientists recovering gear from the sea floor, the consequence of on-demand gear would be the sharp rise in derelict gear that he thinks would ensue from unmarked traps being mangled.

“I’m not in favor of it,” Rego said. “I speak for probably 90 percent of the lobster fleet. I just think there’s no sense in having it with the mandatory closures we have.”

But Rego is also thinking beyond the four-month trial, as many fishermen seem to be, to a possible point in the future when the gear is required year-round. He says cost is the big issue. “The financial impact would just be devastating,” Rego said. “For the lobstering industry, it would be the final nail in the coffin, the way I see it.”

The gear used in the trial, which costs between $300 and $10,000 per unit, said Milliken, is financed half by federal funding and half by NGOs. He said that the high costs have to do with the gear still being in the research and development phase and therefore being produced in small quantities.

It’s unclear what funding would look like post-trial in the case of mandated on-demand gear.

“When we get to that point, that’s when the regulatory policy side takes over,” said Teri Frady, research communications chief at NOAA. She said that historically there is a lag between new gear being required and that gear being available to fishermen in sufficient quantities.

“It’s not really a straightforward process,” Frady said.