PROVINCETOWN — Late April marks the peak of the North Atlantic right whale season in Cape Cod Bay. Since January, more than 180 of these endangered animals have made an appearance here, according to Daniel Palacios, director of the Right Whale Ecology Program at the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS) — nearly half of the 2023 total estimated population of 372. A handful have even been regularly visible from the beaches at Race Point and Herring Cove, grazing on plankton at the water’s surface.

“The year has been good for whales,” Palacios said. The total number of whales visiting the bay last year was around 170. They usually stay until late May before heading farther north.

Palacios attributes the good numbers to the cold winter. “Temperatures have been cooler than normal, and that’s a good thing,” he said, as it drives plankton productivity. The nutritional quality of Cape Cod Bay’s plankton peaks in April, when particularly fatty plankton called Calanus are most abundant.

The Center has reported two dramatic events this spring: a new calf has been seen among the whales now in the bay, while a CCS team has tried but only partially succeeded at disentangling a five-year-old whale with fishing gear caught in its mouth.

The 11th Calf

Right whales breed each winter off the coast of the southeastern U.S. in a stretch of water between Cape Fear and Cape Canaveral. In this area, organizations like Clearwater Marine Aquarium and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission collaborate on aerial surveys, which are typically the way scientists detect new calves.

These calves are enormous, upwards of 12 meters long when born, and right whale pregnancies last a full year, according to the Mass. Div. of Marine Fisheries. This year, as the whales departed north for the summer, scientists thought that 10 whales had been born during the winter.

On an April 18 aerial survey, CCS observers Ryan Schosberg and Annie Bartlett were watching a group of a dozen or so right whales when they spotted an adult whale with a calf in tow. The whale, which the aerial survey team identified using characteristics like scarring and the pattern of rough, hardened patches of skin known as callosities, did not match patterns of adults that have been regulars in the bay. It also did not resemble any of the 10 whales that had given birth this year, Palacios said.

During their observations, Schosberg and Bartlett realized that the adult whale was a female known as Monarch, making this a previously unidentified calf — the 11th of the season.

According to a CCS press release, Monarch was first identified in 1994, and this new calf is her fifth. “We hadn’t seen her in years,” Palacios said.

They sent photos of the pair to Philip Hamilton, senior scientist at the New England Aquarium who manages the North Atlantic right whale photo-identification catalog. Hamilton confirmed their identification — Monarch had had a calf this winter that went unnoticed until she reached Cape Cod Bay.

“We were all excited,” Palacios said. “It was one of those days that every aerial observer lives for.” Palacios said it is unknown where this calf was born, as Monarch was not sighted in the south this winter.

The new calf has not been named yet. Whales are named by the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium, whose partner organizations like CCS vote on the names for 20 right whales each year based on distinctive visual characteristics.

Despite the good news, Palacios said that 11 new calves is a below-average number. The upside, he said, is that 4 of the 11 calves were born to whales that have not given birth before, an indication of an uptick in the number of females becoming reproductive.

Of the 11 calves born this year, 7 have appeared in our waters so far. “That indicates that Cape Cod Bay is also a nursery area where the calves continue to grow and get stronger,” Palacios said.

A Grave Entanglement

In December, an aerial survey team from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration spotted right whale #5110, a four-year-old male, entangled 50 miles southeast of Nantucket. According to NOAA Fisheries, #5110 had a thick line wrapped around its head and around its back. They determined that this qualified as a “serious injury,” and that #5110 would likely die as a result.

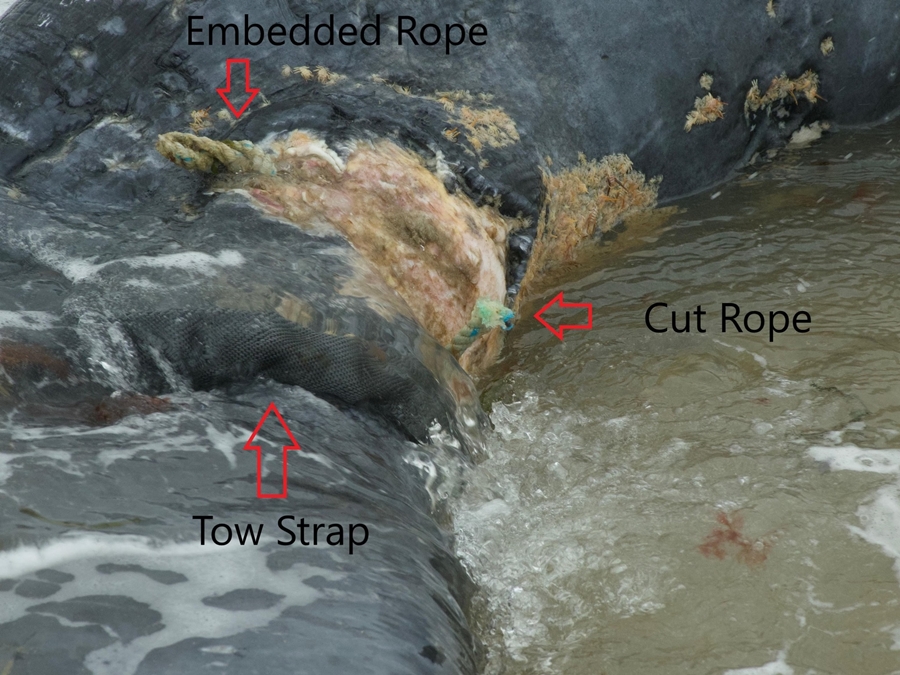

Then, on April 10, after #5110 was spotted in Cape Cod Bay, a CCS team took a boat from Provincetown to attempt a disentanglement, according to Scott Landry, director of the team. They caught up with the whale and managed to cut off 15 feet of rope, but some three feet of it remained wrapped around the whale’s upper jaw, tangled up in its baleen.

In the week that followed, Landry’s team located the whale two more times, but after the initial disentanglement, the whale became wary whenever they approached. “It moves away from the boat and sinks,” he said. With the whale diving below the surface, further disentanglement has not been possible.

This type of entanglement, where a rope wraps around the whale’s jaw, is very common for right whales, Landry said, as they feed with their mouths open for long periods of time. Such an entanglement is particularly dangerous for young whales like this one, since as they grow, the rope will tighten around the jaw, digging into the skin and causing infection.

He said that the three feet of rope still in the whale’s mouth will be difficult to remove. “The more rope that the whale has on its entanglement, generally speaking, the easier it is for us,” he said. “In this case, we cannot get a hold of it. It’s not likely that it’s going to be enough to help the whale.”

The fate of this whale is uncertain, Landry said. For the time being, the whale does not appear particularly encumbered by the entanglement, but that will likely change as it ages.

There is the possibility that the gear could fall away from the whale on its own. Right whale #4120, a young female, was spotted entangled south of Long Island in December, according to NOAA Fisheries, but in February, CCS aerial teams spotted her gear-free.

Without seeing the rope in #5110’s mouth, however, there is no way to know, Landry said. “It could be very bad, or it could be on its way to shedding on its own,” he said. He said that he has seen whales that looked doomed shed their entanglement and has seen whales that seem barely encumbered end up dead.

There’s no way of knowing how many whales die of entanglements every year, Landry said. Based on scarring, around 80 percent of right whales are entangled at least once in their lives.

The Big Picture

For the last two years, Palacios said, the right whale population has risen, but only slightly. In 2022, the population was estimated at 367. That number was 372 in 2023, according to Palacios. There were an estimated 483 right whales in 2011, according to NOAA Fisheries.

“Obviously it’s better than the opposite direction, but we need multiple years of increasing numbers to feel like the population is on a recovery,” Palacios said. Since the entire population of right whales only produces 10 to 20 calves a year, “it takes a while for things to start getting better.”