J. Keith Vincent’s Wellfleet study is covered in felt, the ceiling, walls, and floor lined in a soft-to-the-touch oatmeal and gray. He didn’t choose it for himself. He lets his partner, Anthony Lee, an architectural designer, make those sorts of decisions.

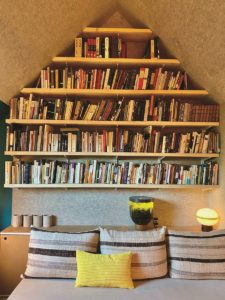

“I wanted a soft room,” Lee says. He’s sitting against one gable-shaped end of the study on a low, oatmeal-colored sofa that doubles as a guest bed. Behind him is a warm glow from the opaque globe of a modernist mushroom lamp (an eBay find, designer unknown), an aquarium (Lee makes them), and, above that, shelves that fill the wall all the way up to the ceiling, neatly lined with Vincent’s books.

Had he seen a felt room somewhere? No. “I thought it up,” says Lee, who teaches at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. “That’s what I do.” Then he adds, “When I think of felt, I think of Joseph Beuys.” He’s talking about the artist who, in 1963, famously wrapped himself in a felt blanket and stayed there for nine hours, grumbling, whistling, and making animal noises. As an installation.

That’s not much like what Vincent does in this room. He is a scholar of Japanese language and literature, a professor at Boston University whose teaching explores queer theory, translation, and the novel. He is sitting at his desk, which runs the length of the wall under a sloping ceiling. At his desk, he faces a skylight overlooking the top of a rustling stand of bamboo.

“It’s incredibly quiet in here, calming. It makes me feel like writing,” he says. The books, he says, are the ones he uses most. “They’re mostly about the writers I’ve been writing about forever.” He is currently working on a biography of Masaoka Shiki, told through haiku.

It happens that Vincent is showing me around his office on Loofah Day. That’s the name given to Shiki’s death day. When he died of tuberculosis 120 years ago, the poet was being treated with loofah gourd juice; the final works in his 24,000-poem oeuvre are about loofah.

Lee and Vincent started building their house, a plain, ur-Cape-shaped structure, in 2013. But the place is still a work in progress. “This is the only room in the house that’s pretty much finished,” says Lee of his partner’s study.

“I loved this space even when it was bare and unfinished,” Vincent says. It was an open, loft-like spot above the kitchen. Two years ago, when Lee came up with the felt idea, Vincent was wary of change.

“But I usually do get out of the way,” Vincent says, “and he’s always right.”

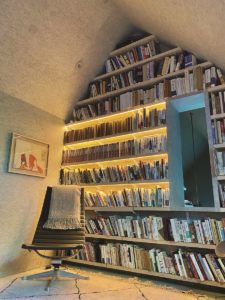

Before the felt could go up, Lee insisted on a new shape for the room. He built a new wall, enclosing the study and creating a hallway alongside it, which leads to his own long, narrow, open office space. He added a peaked ceiling so that Vincent’s studio seems to sit right under the ridge, with gable walls at each end. The space imitates the shape of the whole building, “like a perfect little house,” Lee says.

Except that, at first, the studio space felt too enclosed. The two cut a “window” — really a window-shaped hole — through one end. “It’s kind of like a Rapunzel thing,” says Lee. Through it, Vincent can get a glimpse of Lee in his workspace or look down into the living room. When they finished that job, they cut up the scaffolding they’d used and made bookshelves from the pieces that fill both gable ends of the studio.

Over a weekend, the two applied the felt to the finished shape. Traditionally made of wool, the felt Lee chose is a recycled polyester made by Designtex; it’s about a quarter of an inch thick. The process was a lot like hanging wallpaper, and they worried the glue would not hold as they unfurled and smoothed thick sheets of felt over every surface.

“As soon as we finished, the room felt completely different,” Vincent says. He and Lee were most surprised by the way the felt changed their experience of sound in the study. Talking there, one feels becalmed. Voices aren’t muffled, but there is no reverberation.

Vincent has added a few of his own touches, beyond his books, to the space. Next to the interior opening is a painting by Sadie Benning, “Transitional Effect, Flat Black and Pink (for Douglas), 2012,” given to him by the late Douglas Crimp. On another wall, there is an ink drawing of the 19th-century Kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjuro IX— “the first Japanese actor to appear in a film,” Vincent explains, “he was an actor Shiki loved.”

Lee kept the lower part of one wall bare. The felt wraps around the edge of sloped ceiling just above Vincent’s desk, and the rest of that plane is painted an intense blue. Lee describes it this way: “It’s a deep blue of another dimension. That’s where Keith sits, right where the two planes meet, this cozy envelope and another dimension.”

“Actually, the blue is the exact color of my childhood bedroom,” says Vincent. “I think it was called ‘intense teal.’ ”

“You never told me that,” says Lee.