PROVINCETOWN — Whaling was a difficult and dangerous way to make a living and generally not a very profitable one for members of the crews, who had to face typhoons and hurricanes, onboard fires, food and water shortages, scurvy and other illnesses, and fearsome attacks from the mammoth whales they chased.

But for Black men in 18th- and 19th-century Massachusetts, whaling offered a measure of racial equality not found on land.

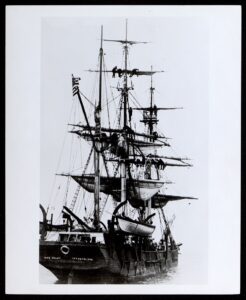

Provincetown was the third-busiest whaling port in Massachusetts, behind New Bedford and Nantucket. Between 1820 and 1920, 161 whaling ships made 902 voyages from Provincetown.

And most of those had several Black crew members.

Whaling captains selected crew members for their skill and experience rather than for the color of their skin. Black men, who had far fewer options for work, made up about 30 percent of the average whaling crew sailing out of New England ports.

“While most black people before the Civil War were slaves or subject to being taken into slavery, on the sea it was different, especially for whalers, who worked freely in the waters off areas where they would be enslaved if they went ashore,” wrote Skip Finley in his 2020 history, Whaling Captains of Color: America’s First Meritocracy. Not only did Black men serve as crew members on whaling ships, Finley wrote, many held positions as officers.

Finley prefers the term “people of color,” because, he said, these crewmen were of African, West Indian, Cape Verdean, Hawaiian, Native American, and other backgrounds.

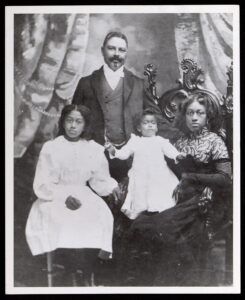

Among Provincetown’s whaling captains, two men of color are known. Collin Stevenson, who was born on the island of St. Vincent in the West Indies in 1847 and arrived here about 1870, was captaining whaling vessels by 1889. Born in Barbados in 1859, William Shorey was the son of a Scottish sugar planter and a West Indian woman of African and European ancestry. He took his first voyage on a whaler in 1876 and spent about four years honing his skills on whaling ships out of Provincetown.

“Provincetown’s whale fleet owners exhibited a cash-motivated racial tolerance,” Finley wrote.

There was money in whales. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Americans depended on whale oil just as we depend on petroleum products today. Oil from whale blubber was used for lighting and for lubricating machinery; baleen went to corsets, hoops for women’s skirts, and umbrella ribs; and spermaceti, a waxy substance found in the head cavity of the sperm whale, was a highly valued commodity used in ointments, cosmetics, and superior quality candle wax.

Ambergris, harvested from whale’s intestines or found floating in the sea, was used in the manufacture of perfume and “occasionally added to wine as an aphrodisiac,” according to the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park website.

“The average white person who went out on a whaling boat was like, ‘Hell no, I’m never doing that again,’ while Blacks wanted to get the hell out of America,” Finley said in a phone interview from his home on Martha’s Vineyard. Positions of responsibility were won by those who proved their skills over several voyages.

Even so, Black whalers faced arrest, imprisonment, and even enslavement in some Southern ports before the Civil War. Finley’s book describes a Georgia law requiring a 40-day quarantine of any ships arriving in port with Black people on board. North Carolina, South Carolina, and Florida began imprisoning Black crewmen in the 1830s. Alabama did not allow ships with Black crew members in its ports, and the Negro Seaman’s Act required that Black seamen be jailed while their ships were in Louisiana ports, Finley said.

Those measures were taken because of enslavers’ fear that the sight of free Black crewmen might inspire slaves to rebel.

Authority at Sea

Georgia Knowles Ferguson Cook, granddaughter of Provincetown ship owner George Osborn Knowles, wrote in 1976: “The whaling industry taught men and boys skills, self-reliance and valor, but took its toll in violence, physical hardships, mutinies and dangerous living.”

In his 1998 book, Black Jacks, historian W. Jeffrey Bolster said that whaling might have offered “the best chances for promotion and responsibility to blacks, but they were notorious for poor pay, and conditions aboard the floating factories that butchered and processed whales were abysmal.”

Bolster called whaling “dirtier, more dangerous, more estranging and worse paying than merchant or coastal shipping.”

Whaling ships could be out of port for very long periods. “Genuine integration did not exist on most American whale ships and violence sometimes flared,” according to the New Bedford Whaling Museum’s website. “In general, however, men who were packed into tight quarters for years at a time under the nearly unlimited power of the captain and the officers usually found it wise to tolerate each other.”

The captain had absolute authority on the ship, while the mates serving under him commanded the whaleboats, lowered once a whale was spotted. Next in the hierarchy were the harpooneers and boat steerers, who enjoyed more privileges than the rest of the crew, followed by those who served in roles like blacksmith, carpenter, or cook. Then came the regular crewmen.

Black captains had the same absolute authority over the crew as their white counterparts. “A black whaling captain might not risk eye contact with a white man on land, but he could flog or shackle that same man at sea,” wrote Finley.

Workers were paid in shares of the net profit, known as “lays.” The captain would get the largest share, while an inexperienced crew member got the smallest.

If profits were low, the crew might not receive any payment. Sometimes they might even owe money to the ship owner for cash advances given to crew members for their families or to spend in ports of call or for items purchased from the ship’s store, such as clothing or tobacco.

Stevenson and Shorey

Collin Stevenson’s career as a captain sailing out of Provincetown started in 1889 on the Rising Sun. From 1890 to 1904 he served as captain, first of the Alcyone and then the Carrie D. Knowles, two schooners owned by George O. Knowles.

Stevenson served as captain on 16 voyages, killing and processing 95 whales with a value of more than $3.3 million, according to Finley. Most of Stevenson’s voyages to the Atlantic and Caribbean were less than a year long, allowing him some time on land in-between.

Stevenson married and raised a family in a house on Race Point, calling Provincetown his home for about 30 years. He was a Mason in the predominantly white King Hiram’s Lodge.

On Jan. 27, 1904, Stevenson sailed the Carrie D. Knowles, with a crew of a dozen, out of Provincetown Harbor headed for Dominica. The ship never arrived. After months of no communication, the ship’s owner and the families of the crew lost hope that their loved ones were still alive.

But hope was rekindled in 1909 when Elisha Payne, claiming to have been a crew member, arrived in Kingstown, St. Vincent, dressed in a tattered prisoner’s uniform. He reported that a storm had blown the Carrie Knowles off course just before the ship reached Dominica, and she had arrived in port in Venezuela instead. The ship was boarded by Venezuelan officers who clamped the crew in irons and threw them into a damp prison in an old stone fortress overlooking the harbor. Payne said he had escaped after hitting his jailer over the head with a water jug. He reported that the rest of the crew members were still alive, but Capt. Stevenson was ill.

Stevenson’s wife, Hannah, canceled her plans to remarry when she heard her husband might still be alive. The storyteller disappeared, however, before he could be questioned further, and the fate of the Carrie D. Knowles and her crew remained a mystery.

After the Barbados-born William Shorey’s four years on whaling ships out of Provincetown, he became third mate on the Boston whaler Emma Herriman. In 1880 he began the three-year voyage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, ending in San Francisco. By then, Shorey had been promoted to first mate.

Shorey never returned to Provincetown. He married Julia Ann Shelton, the daughter of one of the leading Black families in San Francisco, in 1886. They had five children.

Shorey had become the captain of the Emma Herriman in 1885. She was the first of five vessels he would captain over the next 22 years, hunting whales in the Pacific and the Arctic. He had a reputation for bringing both ship and crew safely back to port.

He killed 82 whales, with a value of $7.8 million, according to Finley, before he retired from whaling in 1908 at 49. By that time, the whaling industry had waned as petroleum and other fossil fuels replaced whale oil.

From 1912 until 1919, Shorey worked as a special police officer for the Pacific Coast Steamship Company. He died in 1919, a victim of the Spanish flu.