To the casual observer, Provincetown may seem an oasis of acceptance and peace, a place where one can escape the stresses of daily life. But those who live here know that fierce debate has always been a hallmark of its local governance.

Today’s town meetings offer lots of opportunities for passionate discussion of issues ranging from pickleball to affordable housing. The same was true in 1835, when the construction of Commercial Street was the hot topic of the day; and in 1838, when a couple of contentious town meeting sessions approved the addition of a plank sidewalk by a single vote.

“No matter how much power you think you have, you cannot tell the citizens of Provincetown what to do,” says David W. Dunlap, architectural historian and author of The Provincetown Encyclopedia, formerly titled Building Provincetown. “You can only hope they’ll comply.”

That applies to residents past and present.

“The sheer contrariness of Provincetown’s citizens goes back at least to the early 19th century, as they bought and sold property on land that was actually owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” Dunlap says. The town wasn’t formally separated from the Province Lands until 1893, he notes.

Provincetown was thriving in the first half of the 19th century, thanks to the fishing and saltworks industries and a vigorous commercial sector, all connected to its access to the sea. According to federal census records, the town’s population more than doubled between 1810 and 1840, from 936 to 2,125.

Most of the goods needed to support the rapidly growing community were delivered from Boston by ship.

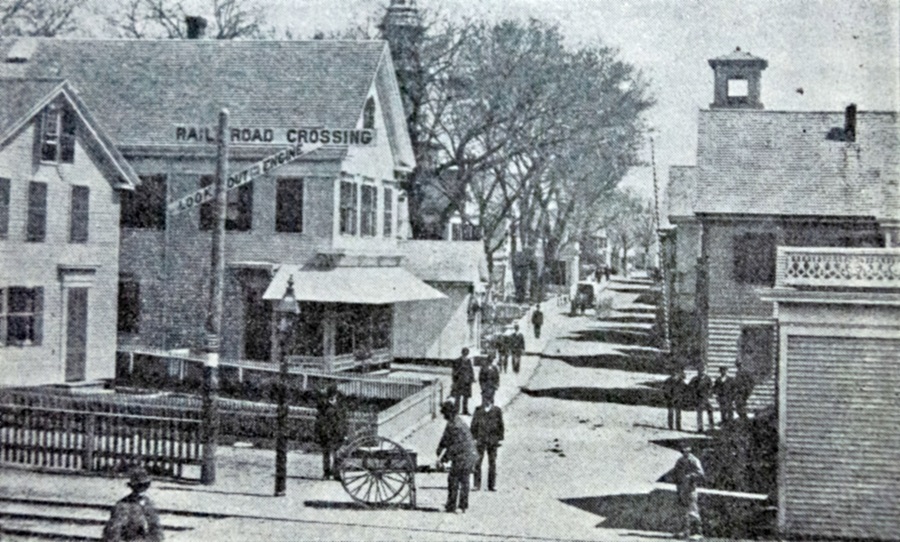

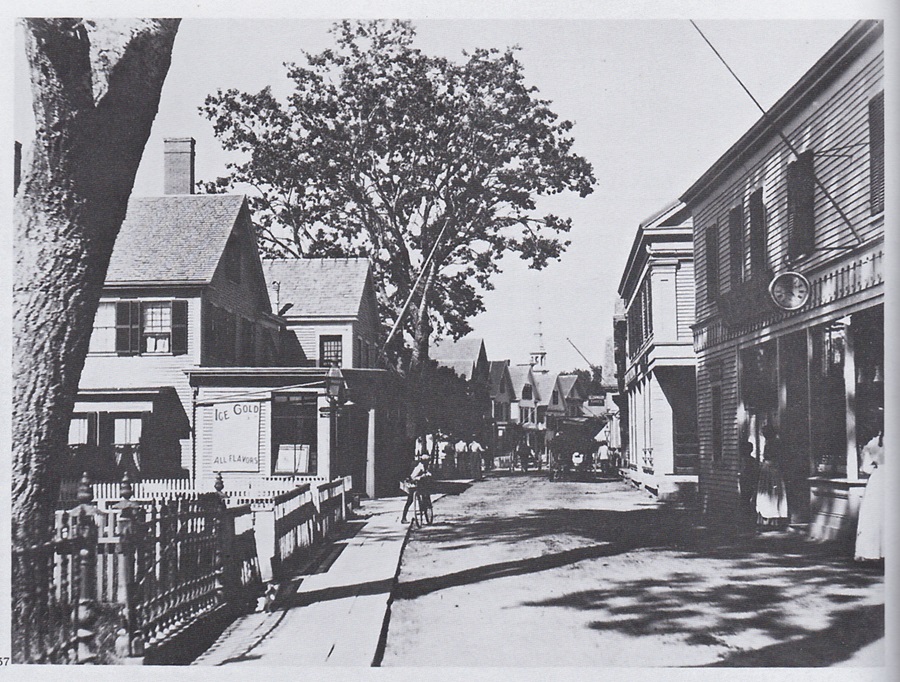

Homes and businesses sprouted along the harbor, with their front doors facing the water. Travel on foot or by cart was mostly along the beach, subject to the rise and fall of the tide. To get to the harbor, school, church, and the homes of neighbors, townspeople traveled by a network of paths.

In The Provincetown Book, author Nancy Paine Smith comments that deeds from that time refer to “the Town Rode,” which must have been the well-traveled path that the Barnstable County commissioners used when laying out what they would call Front Street.

According to the docket of their meeting in October 1835, the commissioners approved $1,273.04 to cover the cost of land taking related to the new road, with 125 property owners receiving some part of that total.

Smith notes that “there was great opposition to such an innovation as a street.” People argued that it wasn’t needed. They preferred to travel along the shore as they had always done. Those whose houses faced the harbor weren’t keen on having a road at their back door, wrote Smith.

Ultimately, the citizens of Provincetown set the width of the new road, constructed of shells and loam, at 22 feet, the standard of the time and just enough for horse-drawn carts going in opposite directions to pass each other.

Existing businesses and houses defined the course that the road through the center of town would take, and there were heated discussions with property owners. One problem arose in the layout of the far West End.

“The name of the problem was Benjamin Lancy,” says Dunlap. Lancy owned a salt works behind his house, and it looked as if his property would be bisected by the new street. Dunlap cites Smith’s description of the encounter between Lancy and an adversary.

“Whoever saws through my salt works saws through my whole body,” said Lancy. To which Joshua Paine replied, “Where’s the saw?”

Lancy ultimately prevailed. “Commercial Street was forced to do a double dogleg,” Dunlap says. “We know it as the Turn, but it’s also called Lancy’s Corner, Kelly’s Corner and — officially — Louis Ferreira Square. Benjamin Lancy’s cussedness literally shaped the town.”

In 1838, one faction of the local populace suggested that some of the surplus money being distributed by President Andrew Jackson’s administration be used to install a four-foot-wide plank sidewalk along Commercial Street. The March town meeting initially voted it down but later approved a motion to reconsider it.

According to Smith’s colorful account, the debate went on for a full week. When it became clear that the vote would be very close, those opposing the sidewalk challenged the citizenship of Abraham Chapman, a sidewalk supporter.

Chapman was outraged by the accusation. The accusers argued that Chapman’s parents were Tories and had left town during the Revolutionary War, moving to Nova Scotia, where Chapman was born. Because he came to the United States when he was six months old, he was not an American citizen, they said.

Ultimately, Chapman’s vote was counted, however, and the proponents of a new sidewalk prevailed by a vote of 149 to 148.

“So incensed were some of the fathers at the use of the surplus revenue,” Smith wrote, “that they refused ever to walk on the sidewalk, and they continued all their lives to plough through the sand.”

The younger people in town meanwhile enjoyed the plank sidewalk, finding it “springing and delightful,” according to Smith.

Provincetown’s website, which includes town meeting decisions dating back a couple of centuries, shows that the initial vote approved plank sidewalks for both sides of Commercial Street. Two months later, a May town meeting voted to run the sidewalk only on the northern side.

Nearly two centuries later, Provincetown Moderator Mary-Jo Avellar says that local politics have always been intense. She got involved in the 1970s, when, she says, “the town was in shambles.”

“They hired a town manager who was under indictment in another state,” says Avellar, adding that town officials got rid of the fire chief without providing a reason. “We formed an organization called SCRAM, which stood for Serious Citizens Revolting Against Mismanagement.” A recall of some selectmen ensued.

SCRAM is credited with helping the town get back on track.

Besides serving as moderator, Avellar has also been on the select board. She says town meeting debate can be lively, but the participants have historically been respectful. There have been a few rough spots, like the discussion of a controversial drop-in center in the 1970s. “There were a lot of drugs in town in those days,” she says.

Last April’s town meeting, when some articles about short-term rentals were on the warrant, was another contentious session. The problem, says Avellar, was that some people didn’t understand the town meeting form of government. “They just think in this kind of democratic system anything goes, but that’s not how it works,” she says.

Tempers had calmed by the fall town meeting, although two police officers were present in case of trouble.

“Few important matters have ever been settled in Provincetown without a kerfuffle, or at least a lot of kibitzing,” says Dunlap. The political scene here reminds him of New York.

“Both towns celebrate their diversity, as they should, but diversity can mean diverging interests, where one group’s solution is another group’s anathema,” he says. “Because Provincetown is so compact and confined, those differences can lead to serious friction. At least in New York, if you don’t like it in Manhattan, you can move to Brooklyn.”