At first, the idea of sharpening your own knives seems intimidating, even a little mysterious — the kind of thing that’s “only for pros.” And it’s true that chefs’ relationships with their knives are intimate, the knife literally an extension of their hands.

A colleague told me that when she worked in the kitchen at the Four Seasons restaurant, the executive chef would walk through the kitchen and randomly check cooks’ knives. If they were dull, he would drop them in the trash, which sounds like some brutal bit of kitchen culture you would see on The Bear.

But knife sharpening can be learned. And it’s worth it for more than one reason.

Google’s first reply as to why sharp knives matter is from the Rochester Medical Center: “A dull blade is more dangerous to use than one that is sharp. Here’s why: A dull blade requires more pressure to cut, increasing the chance that the knife will slip with great force behind it. A sharp knife ‘bites’ the surface more readily.” Sharp knives are doctor-recommended.

If your knives have been rattling around in a drawer since you bought them, you have your work cut out for you. Consider taking them to a knife doctor — a professional who sharpens knives for a living. If you were a city kid, you might remember those old-fashioned knife-sharpening trucks with their clanging bells. Those don’t come by much in our little towns. Here, if your knives need serious rehabilitation, and they’re worth saving, you may need to send them to one of the respected services chefs use, like Korin in New York City or Knife Aid, outside Los Angeles.

And once they’re in shape, don’t just put them back in that drawer. Buy a knife guard, block, or wall magnet for storing your knives to protect their edges.

I recently took my knives to the masters at Korin for a tune-up. In the restaurant world, this place is considered the bomb. Young inked and pierced chefs come and stand in awe, as if they’ve just entered a church. My knives weren’t terrible before, but after some professional care, they felt like new. My chef’s knife now slides effortlessly through an onion. My boning knife cuts meat as if it were butter. There’s real joy in that. That feeling inspired me to take better care of my knives.

But where to begin? The knife world is vast, and there are many helpful online videos that could guide you and side trips into information on metals, shapes, and forging led by super passionate knife geeks. Warning: this subject can take you down a very deep rabbit hole.

Take a breath and remember that no one is an instant expert. Start with some basic parameters and the willingness to approach caring for your knives as a practice — with a generous attitude and patience. The rhythm of motion, the soothing sound, the subtleties of setting the knife to the stone mean being in an almost meditative zone.

How often do you need to go there? Listen to the knife. If it’s dull and not performing well, it’s asking you to give it some love on the stone. This, too, is part of the practice.

Knife sharpening falls into that category of things we know we should do — like exercising more, turning off social media, or calling your mom — but too often falls to the wayside. Doing it, though, you experience noticeable rewards as you chop, slice, and dice, with the bonus of centering yourself in a practice.

Knife Sharpening Basics

The focus here is on sharpening a Western-style chef knife — the kind most home cooks use. These knives have a double-beveled edge, and the blade is curved.

- The Steel. Swiping a knife over a stick steel at a 20-degree angle is helpful with Western knives. This is honing, which smooths out microscopic knicks. It’s great to do between sharpenings, but it is not the same as sharpening because it doesn’t create an edge. To do that, a knife needs grinding on a stone. Many of the small hand-held sharpeners are honing, not sharpening.

- The Stones. Stones have a gritty surface that grinds and smooths out the knife’s edge. Like sandpaper, stones come in grades from coarse to fine. A knife is passed over a coarse-textured stone to form a new edge and then refined and polished on a finer surface. For home use, a two-sided stone with a medium and finer surface is more than sufficient.

There are two types of stones: whetstones and oil stones. Old-school oil stones are inexpensive and work well on Western knives. The disadvantage is that over time oil stones get clogged with the small filings of repeated sharpenings and become less efficient. This happened with my 20-year-old oil stone, and I replaced it with a two-sided whetstone. The difference was dramatic and empowering.

The coarse side of a whetstone needs to be soaked in water for 30 minutes before using. It’s not recommended to submerge both sides because the finer side can crack if soaked. It needs only a drizzle of water.

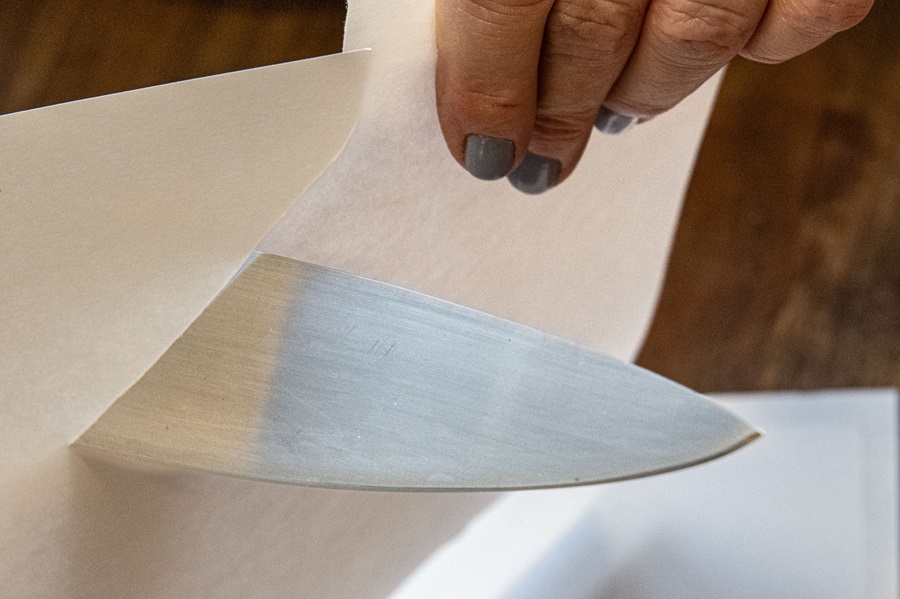

- The Angle. Sharpening a knife is creating two edges with a uniform angle. Chef knives are generally sharpened at a 20-degree angle. Finding and maintaining the angle is the key. This is where practice and patience pay off. Resting your knife on 4 nickels will give you the correct angle.