One year after my mother died, she was with me again, vividly. I was walking through a maze of graves lit by a sea of beeswax candles in a cemetery dating back to pre-Columbian times. I was in Oaxaca, Mexico, and it was midnight on Nov. 1, the height of Día de los muertos, the season of preparation and celebration that connect the living with the dead so intimately there.

The air was dense with the honied smoke of dripping tapers, the musk of a thousand marigolds, and the savory steam of homemade tamales. A country-rock band in cowboy hats played. A crowd of young men wept by the grave of a lost friend. Abuelas in sarapes sat with their phone-scrolling grandchildren, waiting patiently for the return of their dead loved ones. Such returns are not mere metaphors in Oaxaca, but real family reunions of spirit.

There, in that unprotected seam between life and loss, I wept, not just for my mother, but for what it means to be alive. I love everything about Día de los muertos, including the ways in which it is, paradoxically, not about death but about life.

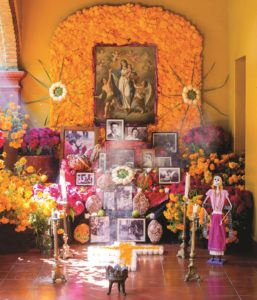

There is food, of course — complex moles and tender sugar-coated breads. There is wit and beauty in the irreverent calaveras — skeleton dolls — and in the Catrina masks and face painting that link the Aztec goddess of the underworld to modern Mexico. There is remembrance and hope in the carefully crafted ofrendas, or altars, that families and friends create using portraits, candles, favorite foods, and fragrant orange and yellow marigold flowers to guide the dead home.

On this anniversary of my mother’s death, the rituals brought her back. Now I understood muertos in a deeper way. As Hector, Miguel’s spirit guide in the movie Coco, put it, “If there’s no one left in the living world to remember you, you disappear from this world.”

Back home, with Oaxaca rich in my mind and soul, I created a family altar of my own, and still do, every year.

For my loved ones, I bake two rich Oaxacan-style panes de muertos, a brioche-like bread, scented with orange flower water and anise seeds. I surround one warm, sugar-coated bread with bouquets of marigolds, photos, and my mother’s favorites: Cape Cod beach plum jelly, nonpareil candies, and a large glass of bourbon. The other is to share right away, with the living.

Pan de Muertos

Makes two 8-inch loaves

1/3 cup whole milk

1 envelope active dry yeast

4½ cups all-purpose flour, plus more for shaping

2 to 3 tsp. orange flour water or vanilla extract

1¼ tsp. anise seeds

4 whole large eggs

2 egg yolks (save one of the whites)

½ cup sugar, plus more, for decorating

1¼ tsp. fine salt

2 sticks unsalted butter, room temperature and soft

Warm the milk in a small pan with 1 tablespoon of the sugar to about 100 degrees (warm to the touch but not hot). Pour the warm mixture into the bowl that fits your stand mixer, scatter the yeast over the surface, and when the granules soften, in about a minute, stir in 1/2 cup of the flour, the orange flower water, and the anise seeds to make a creamy batter.

Cover the bowl with a clean towel and set aside until the mixture begins to plump up and tiny holes break the surface, about 30 minutes.

Beat the whole eggs with the extra yolks, the remaining sugar, and the salt until smooth and stir this into the yeast mixture. Now attach the dough hook and, setting your mixer on medium low, let it gently knead the dough while you gradually add the flour.

When about three-quarters of the flour is incorporated, slowly add 1¾ sticks of the softened butter, 1 to 2 tablespoons at a time. Don’t rush; this may take a minute or so. Continue to knead until the dough is smooth and shiny, 10 to 12 minutes.

Turn the dough out of the bowl. Scrape out any dough remaining in the bowl, then brush the bowl with a little of the remaining butter. Lightly dust your hands, knead the dough by hand briefly, and form into a ball. Return it to the bowl, cover with plastic wrap, and refrigerate overnight.

The next day, turn the dough out of the bowl and cut it evenly in half. Cut off about 1/4 of each half and set aside. Line two baking sheets with parchment paper. Form the larger pieces of dough into rounds and place each in the center of one of the prepared pans.

Divide the smaller pieces in half. Roll one half of each into a round — these represent skulls. Place them on the pans to rise alongside the larger rounds. Cut the remaining pieces of dough in half again, roll and stretch each piece into a log about 6 inches long, place the four logs on the pans, and turn their ends under, pinching them to make bone-like shapes. Cover the breads with towels and set aside to proof, about 4 hours. The larger dough will puff and, when touched, it should feel airy and lighter.

Heat the oven to 350 degrees. Brush the long pieces of dough — the “bones” — with the egg whites and lay them brushed-side down on the large rounds to form a cross on each loaf. Brush the small rounds with egg white, and place one brushed-side down in the center of each of the crossed “bones.” Leave as a round or pinch into a skull shape.

Bake the breads until golden brown, about 30 minutes, or until a thermometer inserted in the center reaches 190-200.

Transfer breads to a rack over a baking pan and brush the warm breads with the remaining softened butter, then sprinkle generously with sugar. Cool. Set one on your altar and share the other.