WELLFLEET — The owners of two houses that represent different chapters in Wellfleet’s history are looking to demolish the structures.

One of them, a full Cape at 45 School House Hill Road, is among the 32 remaining 18th-century houses in town, built in 1797, according to documentation at the Mass. Historical Commission. The owners want to replace it with a mid-century modern style house. But the town’s historical commission voted on Jan. 29 to delay demolition of the house for 18 months.

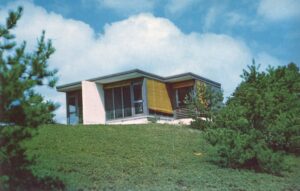

The other house threatened with demolition is from a different era. The 75-year-old cottage at 60 Way #55 is an important example of mid-century modern architecture. It is one of the original 14 buildings designed by architect, arts patron, and bon vivant Nathaniel Saltonstall and his business partner, Oliver Morton, for their Mayo Hill Colony Club. The proposed demolition of the cottage is on the historical commission’s Feb. 26 agenda.

An Original at The Colony

“Spilling down a modest hill near the quiet end of Wellfleet Harbor,” the Mayo Hill Colony Club originally included 11 cottages, plus a kitchen, an office and laundry building, and an art gallery, according to Cape Cod Modern: Midcentury Architecture and Community on the Outer Cape by Peter McMahon and Christine Cipriani. The flat-roofed buildings, designed in the Bauhaus tradition, were constructed of concrete blocks, plywood, and glass. They were positioned to take advantage of the angle of the sun.

The Colony Club, adjacent to the Chequessett Yacht and Country Club, offered amenities that were aimed at attracting wealthy vacationers from Boston. “Once ensconced in their cottage or duplex, guests enjoyed porter and maid service, a fire laid each morning, a snack in the fridge, and optional meals from the continental casserole kitchen,” wrote McMahon and Cipriani. Over the years, Elizabeth Taylor, Paul Newman, Faye Dunaway, literary and social critics Lionel and Diana Trilling, and many other artists and authors stayed at the cottages.

Saltonstall owned the cottage complex until 1963 and had a summer house there. Loris Stefani, a Boston artist and interior designer, and his partner, Eleanor Sallen (who later took the name Stefani), bought the property from Saltonstall in 1963 and opened the rental cottages to the public, changing its name to The Colony. Loris died in 1978, but Eleanor continued operating The Colony until her death in 2019. The complex then went to her son, Jeffrey Stefani.

But the cottage at 60 Way #55, one of the originals designed by Saltonstall and Morton, is not part of what Jeffrey Stefani inherited. That’s because it had been sold in 1978 to Edith Keyes Harris.

Eleanor Stefani disputed the validity of the cottage’s 1978 sale to Harris on the grounds that she was not a purchaser in good faith. The cottage had been sold to Harris by lawyer and businessman Charles E. Frazier Jr., who had stepped in as part of a refinancing scheme when The Colony was in financial straits. In 2008, the Land Court confirmed that Frazier’s authority to sell property on behalf of The Colony had lapsed before he sold the place to Harris. But in the end, it concluded that Eleanor had, by not challenging the sale in a reasonable time, ratified the deed.

The cottage’s current owner, Westford resident Douglas Metcalf, who hopes to demolish it, has an unusual relationship to the property: he was co-executor of Edith Keyes Harris’s estate, according to court documents.

McMahon, founding director of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust, conceded that 60 Way #55 is a little “down at the heels” but said that doesn’t mean demolition is the only option. “Preserving it is important, and there are ways to do that,” he said.

A preservation restriction could have prevented this potential demolition, McMahon said. That almost happened a decade ago. In 2004, Stefani began an application to the Cape Cod Commission to designate The Colony as a District of Critical Planning Concern and to have it listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2022, Sarah Korjeff, historic preservationist at the Cape Cod Commission, told the Independent that the process was never completed.

“It happens all the time that people talk about preserving the house,” said McMahon, “but they don’t do anything, and it’s left up to the children.”

Jeffrey Stefani now lives in the building that had originally served as the Mayo Hill Colony Club’s art gallery. He built a two-story addition in 2020. Last summer, he put the rest of The Colony still in his hands on the market, asking $5 million for his 8 cottages on a single four-acre lot. The cottages are small, with units ranging from 500 to 750 square feet.

This week, Stefani said he had not been notified of the proposed demolition of the cottage at 60 Way #55.

A Demolition Delayed

Attorney Ben Zehnder, representing homeowners Scott and Carolyn Kilpatrick, who live in Providence, R.I., told the historical commission on Jan. 29 that the 1797 house at 45 School House Hill Road that the couple bought in 2017 wasn’t in terrible shape but had never really been updated.

“It’s a structure that’s nearing the end of its useful life,” Zehnder said. Small rooms, narrow halls, and a lack of heat on the second floor would prevent the Kilpatricks from aging in place there, he said.

The Kilpatricks are looking to demolish the 228-year-old house and replace it with a mid-century modern style house, where Zehnder said they would live when they retire. The couple actually wanted to keep the original house and build a new one on the same property, their lawyer said, but could not do so because the house is in the National Seashore District, where the square footage is limited to 3,600. “So, they’re kind of boxed in,” Zehnder said.

Zehnder suggested that, as the house is dismantled, the owners could work with the town to preserve certain historic elements. Some of those could even be incorporated into other homes, he said. The 18th-century house is not visible from the road, he said.

While the commission can’t prevent the demolition of a house that is historically significant, it can delay the demolition for up to 18 months. The idea is to give the property owners time to consider alternatives.

Commission co-chair Timothy Curley-Egan, who runs a drafting and design business, and member Kevin Sheehan, who does historic restoration work, both argued that the 1797 house could be made livable year-round based on past projects they have done.

One way would be to build an addition. “You’re preserving what has stood for hundreds of years but also bringing something modern into the mix and allowing them to co-exist,” Sheehan said. “It bothers me we’re on a tack that ‘if it’s inconsistent with my lifestyle, I eliminate it.’ ”

Countering Zehnder’s observation that his clients’ house is not visible from the road, co-chair Merrill Mead-Fox said that historic houses are more than decorative elements for a town. “These buildings are a physical connection to the stories and the lives of people who gave the town its identity and its defining characteristics,” she said.

“They’re irreplaceable if lost,” Mead-Fox continued, “and the job of the commission is to do everything we can to prevent demolition of significant buildings like this.”

The commission voted unanimously to impose an 18-month demolition delay.