Much has been made of the Greatest Generation and World War II, mostly by Baby Boomers, looking back on the sacrifices of their parents. In the 1960s and ’70s, during the Vietnam War and the heyday of its peacenik counterculture, young people looked at their parents with alienation, creating the so-called Generation Gap. In more recent times, there has been a correction — a wave of nostalgia and revisited history, extending from Tom Brokaw to Saving Private Ryan.

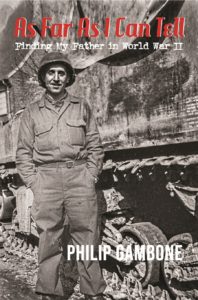

Philip Gambone, a frequent summer resident and visitor to Provincetown, has a unique approach to this generational evaluation. In his memoir-biography As Far as I Can Tell: Finding My Father in World War II, published by Rattling Good Yarns Press in January, he traces the experiences of his father from boot camp to D-Day to V-E Day, and he does it in a way that will resonate deeply with many locals, as a gay man trying to find an intimate connection to his late father.

It’s mostly an effort of personal history reconstructed, because his father chose not to discuss what happened to him in the Army — as a tank gunner in the Fifth Armored Division, landing at Utah Beach in Normandy, caught up in the wintry slaughter of the Hürtgen Forest and Battle of the Bulge, and going as far as the Elbe River in Germany, outside of Berlin, as the war came to a close.

Gambone, who grew up in Watertown where his father ran a dry-cleaning business, went to Harvard at the height of the Vietnam era, graduating in 1970. He eluded the draft, getting his 4-F exemption by admitting his homosexuality, which, in those early days of gay liberation (the Stonewall Riots erupted in June 1969), was done more out of fear than political rebellion.

“I came out as a sexually active gay man in my sophomore year,” Gambone tells the Independent. “The guy I had an affair with, that I maintained throughout my college career, was a graduate student.”

He was neither close nor distant with his taciturn, easygoing dad, a high-school grad from Canton, Ohio, who provided him and his three younger brothers with a stable, middle-class Italian Catholic home in suburban Boston. Gambone came out to his parents in the ’80s, remained in touch during his father’s decline and death from leukemia in 1991, and lived through the death of a partner during the height of AIDS.

What makes this book of wartime experiences so different is that it’s explicitly based on Gambone’s yearning to understand his father and to build intimacy between them. Besides the years of research, documentation, and interviews, he physically travels to the places his father went: training camps and mostly defunct Army bases across the U.S. and in England, and the theater of war in France and Germany.

A ghostly modern reality is transposed on the history of Nazi terror, and, throughout, Gambone balances the personal testimonies of his dad’s military units with the record of the grander historical events that were taking place. The sense of place you get, from the architecture of surviving churches and memorials to the dead, brings an immediacy to the past.

“There are places, especially in France, where I knew my father was, because there was only one street in a town,” Gambone says, and there’s a record of his tank battalion being there.

Without intruding or imposing on his father’s tale, he modestly offers the context of his own life and motivations — the “parallel secrets,” he says, of his father’s witnessing and participation in the killing fields of war and Gambone’s own evolution as a gay man.

Because of the richness of the tapestry Gambone weaves — including, at one point, the events described in actual medieval tapestries he comes across — the European war history he covers never feels tired or extraneous. He’ll fill in a moment when nothing is happening militarily with anecdotes of soldiers in the field and on leave in specific towns (about sexual exploits, of course, and other forms of entertainment), and try to imagine his father, a devout Catholic, in such situations.

This insistent personalizing turns a predictable story — the war’s outcome is no secret, as is his father’s survival without significant injury — into a tense and dramatic one. The number of battles and towns, and the military strategy and technology involved, can get numbing when separated from human experience (trench foot, lice, sickening odors, confinement). War, from a soldier’s point of view, alternates long periods of drudgery with explosive, traumatic scrambles to survive and succeed in one’s mission. And, when the fighting is unceasing, it itself becomes drudgery. A memoir-biography such as this makes that palpable.

Gambone’s many years of teaching writing (in high schools and college extension courses) and his expertise in art and history turn As Far as I Can Tell into a terrific read. The prose is direct and clear, and his occasionally poetic and philosophical points are made accessibly, without pretension. Almost to a fault, he never overreaches: as his title indicates, he makes no claims to anything he can’t substantiate, and the documentation (nearly 100 pages of it) is exhaustive.

Gambone has written award-winning fiction and nonfiction, queer and otherwise, and he even worked at Tim’s Used Books here in Provincetown in one of the summers he lived here. He had a show on WOMR in 1993, interviewing gay and lesbian authors. It’s a gift to have him in our midst, and to immerse oneself in the bounty of his familial exploration. His father might seem to be a shy, ordinary man on the surface, but Gambone shows his story to be truly heroic, with all the limitations a given. It’s a genuinely American epic, one we all can be proud of.