PROVINCETOWN — What a gorgeous monster! First, its size: over nine feet long and over 700 pounds. Then, its unreal color: dark steel blue with green reflections, merging into gun-metal gray, with scimitar-shaped fins and bright yellow armored finlets. What an otherworldly and wonderful-looking thing. Winched up at the dock and hanging by its tail, its majesty still overwhelms the pallor of death. It is overpowering, a large and alien being in our midst.

Josiah Mayo stands beside it, beaming. These fish are hard to catch and hard to kill. It can take days to hook one and then an hour or more to bring it in and dispatch it. It is a test of strength, endurance, and skill. There is something of a swagger in Josiah’s posture as he displays the body of his defeated opponent. He deserves to feel this way. It was an intense fight, from the first bend of the rod — “The fish hit like a train,” he says — to the gradual working it in, as it circled the boat and tired. Then, sticking it with a harpoon, lashing it to the boat with a tail rope (“The fish is ours”), and bleeding it out. It was an accomplishment, and “a real charge.”

But there is a sadness in this scene as well: something so big and beautiful destroyed. I say the same about any prey brought in, any animal harvested. But the sheer size of the tuna — one of the largest fish in the ocean — makes it special. Melville, in Moby-Dick, describes a dying whale as “unspeakably pitiable.” It is also the extraordinary physiology of the tuna: warm-blooded, its body temperature 20 degrees above ambient water, swimming up to 40 miles an hour, charging across ocean basins. The tuna makes us confront our carnivorous nature.

But there is the money. At $5 a pound, this fish will bring, dressed, at least $2,500. This is, actually, “a pittance,” Josiah says, considering the hours spent at sea, the many days no fish are caught, the cost of fuel and the expensive hardware necessary to catch a tuna. And this is far less than what one fish brought in during the heyday of tuna fishing, in the ’90s, when the Japanese were paying big-time prices, our economy was roaring, and our restaurants were full. Those were the days of the $20,000 fish.

The pandemic and its effects on the economy contribute to the price drop, but there are other problems. There is international tuna “ranching”: juvenile tuna are caught and contained in pens in the Mediterranean and South Atlantic and harvested when the market price is right. Locally, recreational “tuna yachts” compete with commercial fishermen. People who make their living catching fish (as Josiah and his captain, Michael Packard, do) have to contend with anybody with a fancy boat and gear and $25.00 for a permit. We need a more rational fishery, Josiah says, one that maintains a sustainable yield not just for the fish stock, but also for the fisherman, for the industry. He longs for an “artisanal fishery.” Access should be controlled, but how? Today’s fisherman must be an ecologist and a businessman, wrestling with contradictions.

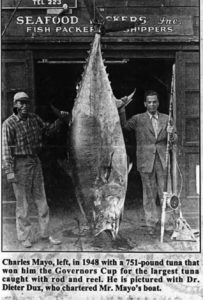

Humans and tuna have a mixed-up history here. In the 1950s, tuna were so thick they were considered a navigational hazard, but they were hardly worth catching. Josiah’s grandfather, Charlie Mayo, who actually created the sport-fishing industry for tuna, got five cents a pound for the “horse mackerel” he caught. Then came the commercial purse seiners and their spotter planes, until all that was banned. Tuna have since been considered endangered, and maybe they still are, but this year saw many big tuna caught in our area. (See “At Tuna Negotiations, U.S. Rejects Advice of Scientists” by Johnny Liesman in the Dec. 3 Independent.)

I believe every animal is here to teach us something. I believe the tuna tells a great story: beyond being just “seafood,” it is wildlife of the most magnificent kind. It embodies the vastness of the ocean, an ecosystem that could produce such a sizable monster. Like the whale, it reminds us that perhaps we have not quite ruined everything just yet. Harvesting it, then, is akin to a sacred act. When we celebrate it, we celebrate the ocean.