PROVINCETOWN — On a Sunday morning in November, the low tide and lure of fresh foraged food drew many recreational shellfishermen to this season’s designated clamming area, the west side of the dike, known locally as the breakwater. A bit further into the marsh, burrowed in the creek banks, nocturnal purple marsh crabs awaited their time to forage, after dusk and at high tide.

Meanwhile, the West End salt marsh — the host to all this activity — is dying. The dike both disrupts natural tidal exchange and prevents crab predators from entering the marsh. Without predators, purple crabs are taking over and devouring vegetation, rendering the marsh defenseless in the face of sea level rise. In 2017, a remedy proposed by the Army Corp of Engineers was killed at town meeting.

After visiting the West End this year, Stephen Smith, a Cape Cod National Seashore plant ecologist, said he could not believe how much the marsh had deteriorated.

“An insane amount of vegetation has been lost from crab grazing,” he said, “and the marsh surface has been lowered substantially from subsequent erosion and soil collapse.”

Salt marshes are critical coastal habitats for many important bird, fish, and shellfish species; they provide nursery grounds, act as biochemical filters, and protect shorelines from erosion. According to the Cape Cod National Seashore (CCNS) website, salt marshes are “among the most biologically productive ecosystems on earth.”

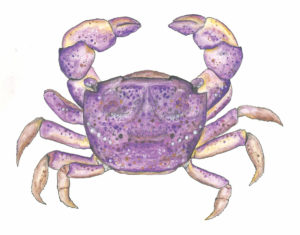

Evidence of the herbivorous purple marsh crab (Sesarma reticulatum) feasting is apparent along the lower banks of the West End marsh. Their continuous grazing on vegetation, particularly cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), is largely responsible for the salt marsh dieback now evident here.

In recent years, the purple marsh crab has proliferated dramatically. “At normal population densities,” said Smith, “there are few impacts, but at high densities, they can continuously graze on vegetation such that plants can no longer resprout, and they die.” When the vegetation dies, the exposed areas erode and collapse.

Salt marsh peat, said Smith, is mostly made of old root material that builds up over many years. When vegetation is lost to crab grazing, there are no longer roots to bind the soil. As a result, he said, “one winter storm can wash away two vertical feet of peat from a creekbank that took thousands of years to form.”

The CCNS found evidence of marsh dieback when it began monitoring the West End salt marsh in 2003. In that year, no purple marsh crabs were found, said Smith.

But by 2008, when Conservation Biology published new evidence from Smith’s research, the crabs were clearly implicated. And die-off here, said that report, was an “alarming addition to the patchwork of marsh vegetation die-off events recorded throughout the western Atlantic coast over the past decade.”

Since then, the dieback has only worsened.

The Role of the Dike

Though considered native, purple marsh crabs have not always inhabited Outer Cape salt marshes. Thirty years ago, they could be found from Florida to Woods Hole. Today, their range has expanded throughout Cape Cod marshes, with some exceptions, said Smith.

“The big problem with the West End marsh now, we believe, is the breakwater,” said Smith, “which doesn’t let any fish predators into the system.”

Striped bass, dogfish, cunner, and tautog would normally eat the crabs. There is also evidence that some fish predators have declined because of overfishing, said Smith.

Another factor could be that ditching the marsh for drainage created an artificial edge, resembling creekbanks, said Smith, “which happen to be Sesarma’s favorite spot.”

In addition, because the dike limits daily tidal exchange, less marine sediment can settle in and contribute to vertical growth. “Coastal wetlands maintain their elevation relative to rising sea level by building soil volume,” said U.S.G.S. research scientist Meagan Eagle at the 2020 State of Wellfleet Harbor Conference.

Before the industrial revolution, Smith explained, marshes could keep up with sea level rise by building one millimeter of peat per year. Sea level is rising at a rate of 3.5 millimeters per year and is expected to reach at least one meter above current levels by 2100. “It doesn’t seem like much,” said Smith, “but it is if you’re a marsh.”

The Dike Modification Plan

In 1914, the Army Corp of Engineers completed construction of the breakwater, formally known as the Long Point Dike, to preserve Provincetown Harbor. The town has in recent years looked into opening a section of the dike to restore the marsh habitat.

In 2006, the Provincetown Board of Selectmen requested an Army Corp feasibility study on modifying the breakwater. After nearly a decade of negotiation, the study kicked off in 2014 and was completed in 2015. In the fall of 2016, a draft project proposal was released for public comment. It involved a 10-foot breach in the dike, spanned by a walking bridge, which would allow large fish and invertebrates to enter the marsh.

The chair of the Provincetown Conservation Commission at the time was Dennis Minsky. He recalled the project being “very unpopular,” with the main concerns being its effect on the shellfish area.

The current chair of the commission had a similar impression. “Everyone felt it could be a disaster,” said Alfred Famiglietti, who, with his husband, owns an active oyster farm near where the bridge would have been built.

Some feared that strong currents could suck swimmers and small boats to danger, and that large marine mammals and fish could be trapped at low tide in new deeper tidal pools, Famiglietti said. Another objection was that the proposed walkway over the breach would signal that the dike was intended for pedestrian use, leading to liability for the town.

Hydrology was not included in the Army Corps study, said Rex McKinsey, the town’s project liaison. Because of this omission, it is unknown whether the proposed design would create tidal currents that could disrupt aquaculture. But if designed in a low spot of the dike, the opening could be beneficial to the marsh ecosystem, McKinsey said.

Former Selectman Raphael Richter recalled that, although the Army Corps and scientists from the National Park Service concluded the project would have no negative effects and that equalizing the tidal flow would create benefits, local environmentalists and clammers thought the project might cause inadvertent damage.

At town meeting in the spring of 2017, the Long Point Dike Improvement Project article was indefinitely postponed. “I think,” Richter said, “ultimately, town meeting decided to listen to the more local contingent and their concerns.”