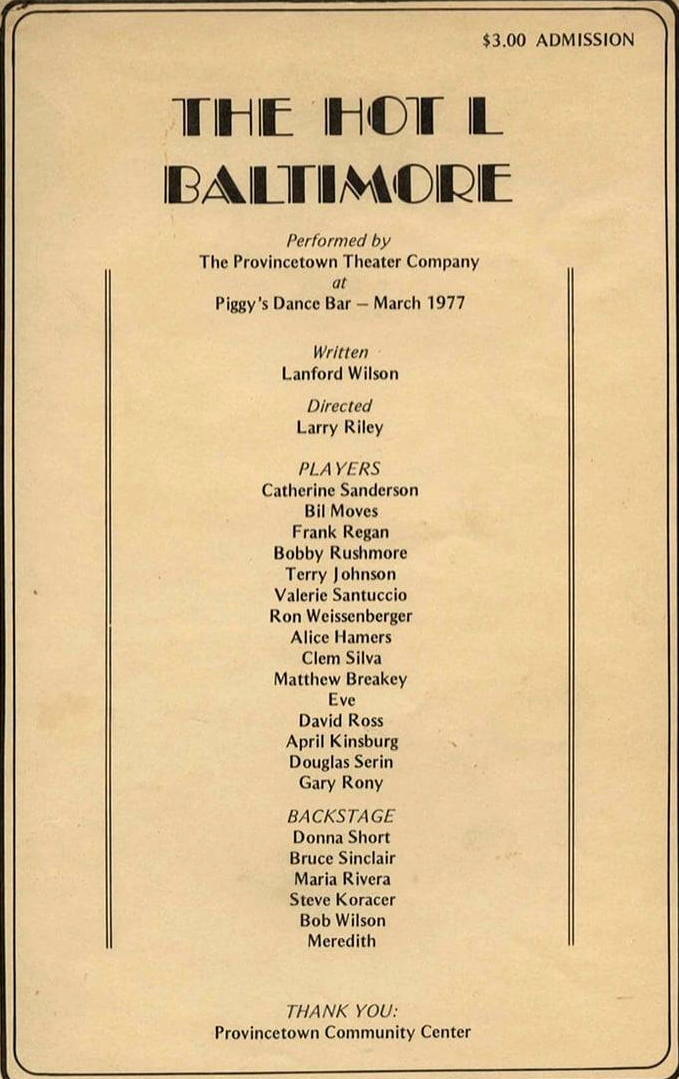

Ask people who lived in Provincetown in the 1970s about Piggy’s — a modest bar filled with salvaged wood on Shank Painter Road — and you’re practically certain to see their faces light up with memories.

“If you missed a night at Piggy’s, even in the middle of winter, you were missing something,” said Nancy Ann Meads, who recalled waiting tables at Café Edwige at age 17 and running to Piggy’s after her shifts. “It did not matter if you were gay or straight or a barbarian or a hippie — everyone got together and was having a good time.”

“It could be a Tuesday in a blizzard — people would walk through snow to get to Piggy’s,” said Marie Pace, who opened a leather clothing store on Kiley Court at age 17 and also finished her nights at Piggy’s.

“I remember dancing with Robert Motherwell while Ciro Cozzi and Norman Mailer boogied in the corner,” Pace said. “We would dance night after night, and we were all skinny as rails because we were working so hard.”

“You could find anything and anybody there,” said Channing Wilroy, who in the 1970s worked in restaurants and stayed in rooms that rented for $9 a week. “You could get picked up just as easy if you were gay or straight — it didn’t matter.”

The bar at 67 Shank Painter Road had existed before the ’70s — it was the Pilgrim Club as early as 1962, according to David W. Dunlap’s Building Provincetown. But the place became suffused with something special around 1968, said David Bishop, who was hired to tend bar there on July 4th weekend 1969, just a few months after Reggie Cabral took over the property.

“Reggie had owned the place for a little bit, but something happened and all the staff was either in the hospital or in jail and there was no one to open the bar,” Bishop recalled. “Two of my roommates and I went to the A-House, which Reggie also owned, and he told me he’d always liked the way I looked, and we got hired on the spot.”

The bar opened at 10 p.m. but was a ghost town until 11:30, when it would suddenly be slammed, Bishop said. “It was called Piggy’s Truck Stop for a while, and then eventually just Piggy’s, although when we were designing the T-shirt, we had a big argument about how to spell it.

“It just became a really cool place,” Bishop said. “One New Year’s Eve, someone got arrested for smoking pot in the parking lot and everyone in the nightclub threw money in a hat to bail him out. That’s the kind of place it was.”

In the winter of 1969, Piggy’s hosted a weekly “beggar’s banquet” on Monday or Tuesday nights, Bishop said. “Everybody brought whatever they could cook really well and put it on the bar or passed it around. You didn’t have to pay anything or buy anything, and we did that every week for a couple of winters.”

Several people emphasized how cheap it was to live in Provincetown back then.

“I opened Spiritus Pizza in 1971, and I used to dance at Piggy’s and then run down Court Street at closing time to put pizzas in the oven ahead of the crowd,” recalled John Yingling. “The town was different back then — it was full of poor people and artists and young people, like really a lot of young people.

“You could rent an apartment for $50 a month, and you couldn’t go down any street without seeing signs that said, ‘Apartment for rent, room for rent,’ ” Yingling said.

“There were so many places for people to rent because there were no condos at the time — it was all guest houses and rooming houses and apartments,” said Meads. “There were all these wonderful little cubby holes, and now there’s no place.”

It was easy to be young in other ways, too.

“There were like four cops in town then, and they had better things to do than sneak into bars and see who was drinking,” Yingling said. The 26th Amendment had lowered the voting age to 18 in 1971, and 29 states lowered their drinking age to 18 soon after that.

The police did take an interest in the men gathering at Piggy’s, though: they raided the bar and arrested seven men for dancing with other men in 1970.

“Piggy’s got busted because it was illegal for a guy to be dancing with another guy,” Bishop said. “They were all brought to court, and Reggie asked the judge if he could ask a question, and then he asked the arresting officer, ‘So which boy here was dancing with which boy?’

“The officer said, ‘I don’t know. They were all dancing together.’ So the case got thrown out of court because they had no evidence that anyone was dancing with anyone in particular,” Bishop said.

After that incident, though, the police presence was light.

“There would be a hundred cars packed into the parking lot around Piggy’s, and they weren’t as aggressive about drinking and driving in that era,” recalled Bill Evaul, who ran the New Moon Magic Theater, a successor to the Weathering Heights Dinner Theater, in 1971. “People came from everywhere to be there — it was like the Mud Club in New York, or CBGB — and there’d be a celebrity in a tuxedo next to somebody in fishing boots.”

Paul Tasha worked the door, and was “tough, but fair — altruistic, even,” Evaul said. “He really kept the peace.” His brother Carl worked the door, too, and it was hard for local kids to get in too much trouble with them there.

“Sometimes we kids would be there, and our parents would be there, too,” said Lisa King. “We never got away with anything because everybody knew us.”

The management at Piggy’s changed several times in the ’70s and early ’80s, but it didn’t seem to hurt the vibe. Several people pointed to the AIDS crisis in the mid-1980s and the end of easy-to-find rental housing as the forces that killed the party.

“A lot of money changed hands turning apartments into condos,” said Wilroy. “The rental market dried up, and it started becoming a rich man’s town.”

“There were so many places to live back then that no longer exist,” said Meads. “But that changed everywhere, not only here — and there’s still so many things about this town to love and enjoy.”

Dance Fever

Howie Gruber rises to the final degree

By Arnie Charnick

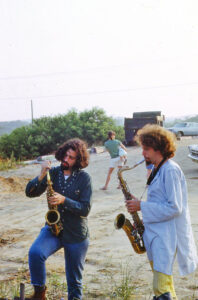

Surely it was common enough in the wild wicked ’70s for breeders and queers to be dancing up a storm together at mixednut clubs everywhere, and Piggy’s was the purrfect place to manifest that kinda fabulous fun; me, representing the straightaways, jumpin right into the nightly rugcutting fray and shakin a leg or two, not only with the chickitas but also my fave gayboys, number one among ’em bein Howie Gruber, the Chef Boy á Deelight (and owner) of Front Street.

Howie was a diminutive dude, all the more easy to disco dominate, sometimes lifting him off the floor and wrapping around him in a lovable hug as we whirled, zigging and zagging betwixt the hive of high and happy humans, while my kids’ mom Peyton kept everyone moving nonstop to her dynomite deejaying.

And so it went, almost every night from eleven-thirty till one.

I get confused about the timing, and place, and details, so pardon my drugaddled brain, but years later when nowhere was spared the Plague, particularly our tinytown at the tippytip of Cape Cod, and Howie, tho hanging in there for longer than lots, was finally about to rise outta his mortal coil, and I was about to drive down to New York at the end of the season, I was told I could say goodbye to my deardear friend if I stopped by the house where he was being cared for by his posse of pals, so I did.

It was evening, and Howie was lying on a couch, frail to the final degree, on the verge of the void, but so surrounded by love he was smiling the same kinda smile he always smiled, me verging on tears but keeping it together enough to say, “You know Howie darling, you were always my favorite dance partner at Piggy’s, and I sure miss shaking a leg with you, so when you get to heaven please please please wait till I get there, and save the first dance for me,” cornball that I be.

And then, beyond what appeared to be physically possible to achieve, given his skeletal immobility, my dancing queen rose from the sofa as far as he was able, stretched out his arms in an effort to hold me in a locked embrace, and in a barely audible whisper said, “No, no, Arnie, let’s not wait. Let’s dance now.”

And then fell back into his stuporous state.

I kissed him goodbye, got into my car, and sobbed all the way to the city.

He died the next day.