EASTHAM — As a recent student of landscape design — an endeavor that involves examining the layout and imagery of the famous gardens of the world — I couldn’t help but notice an obvious throughline that connected their disparate compositions, a commonality that, inexplicably, was missing from both the syllabus and the textbook: many of those gardens would make for killer mini golf.

The English countryside gardens of the 18th century inspired this notion. Stourhead and Painshill, to name two, are filled with constructions that would be right at home in the vacation game. Faux grottos, fake ruins, and replicas built in miniature were designed to thrill garden-goers as they traversed the grounds.

My revelation soon escaped the British Isles. The longer I considered it, the more clearly I could see myself navigating an orb down the zigzag paths of the Lion Grove of Suzhou, playing through the spray of the dragon fountains of the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, tracking the blur of my ball as it swept down the famous cascading handrails of the Alhambra. I began to dream of each landscape masterpiece condensed into 18 holes of perfect putt-putt.

Many gardens of old could be imagined as mini-golf courses. But could any old mini-golf course be a garden? What sort of designed landscapes await the player here on the Outer Cape? How do they compare to the famous gardens of the world? I decided to traverse the grounds of the Gift Barn to find out.

The color red spurs movement in the garden — it can be used to usher people around a corner or to spark conversation. Red petunias, red geraniums, and red daylilies guided me from the parking lot to the ticket booth to the entrance, where a large crimson maple continued the palette.

It was a scorching day without clouds or a breeze. The red flags that indicated the course’s order hung limp, their numbers obscured. I was spurred to move, but to where? I pretended the disorientation was deliberate. As I opted past a tractor and down a path guarded by an owl and a hawk, I wondered what the landscape designer was trying to say. Was there a fake rodent problem on this fake farm? Or was a deeper story being told?

After putting through a covered bridge, I got an answer: in front of me stood an Alberta spruce with a massive reversion, a limb that somehow had drawn from the deep well of its genetic code to override the conical shape of its cultivar. In a formal garden, this reversion would have been promptly clipped. Here, the aberration was wild and huge, giving the tree a figure unbefitting any garden I knew. But when I spied a pair of googly eyes looking back at me from its boughs, I knew exactly what this place was.

I was in a modern-day Sacro Bosco, the Park of the Monsters.

The Duke of Bomarzo’s 16th-century Italian garden was unusual, to say the least. He commissioned Sacro Bosco out of grief for his wife; the place was intentionally designed to be “a temple of dark emotions, madness, and irrationality,” wrote Linda A. Chisholm in The History of Landscape Design in 100 Gardens, starkly contrasting with its contemporaries that valued symmetry and beauty. Sculptures with grotesque proportions left visitors uneasy. Rumors swirled that a violent crime had been committed on the grounds. Generations of locals shunned the park as it grew in both disrepair and infamy.

Having found myself lured into a garden where horrors might lurk, my heart began to race. I warily approached the next obstacle: a turtle’s butt.

Man’s dominion over animals and the land was, I noted, a central theme here. Players must putt underneath and through myriad farm animals and their coops — all precariously balanced over the fairway. Abandoned farm implements used as decor reminded players of the Cape’s unsustainable agrarian past, and a dried-up wishing well at hole 6 awakened fears of depleted resources. I tossed in a quarter for luck and rounded a bend.

A second monster now straddled the way before me: a 15-foot rabbit. It wore blue overalls, which suggested sentience. Its feet were chained to the deck: a prisoner. Had this creature once tried to hop away? I froze as if before a carrot-wielding sphinx. What was the riddle I was meant to answer? Was it daring me to continue?

I putted through without incident.

The leporine goliath signaled a shift: man’s superiority to nature was now in doubt. As I next sent my ball barreling through a bovine’s legs, a breeze carried a waft of grilled burger from the restaurant adjacent. A demonic tree stump found perverse pleasure at this morbid coincidence. The course’s flags now waving, a determined bull fixed its gaze into a corner, refusing to be baited into a red-induced rage. Was I being shown that man’s true self was but a tormentor and that nature was rising in opposition?

The loop-de-loop of the 12th hole suggested that the tables had fully turned and man was no longer in charge at this animal farm. I quickened my pace. Along the final stretch, the animals were now off the green and liberated, but mercifully they were not yet empowered. A still-yoked nag stared blankly, too worn to take revenge. A cow, surely mad, grazed the wooden decking. A billy goat gave me the side-eye.

At hole 17, a shaded bench tempted the weary visitor. The tired soul who would choose to sit, however, would do so at the foot of a 10-foot-tall chicken — a fitting conclusion to a garden hell-bent on reversing the natural order and bringing man into submission. I defiantly remained upright, refusing to be a disciple of this chicken-god.

The sound of water came from somewhere ahead. I was being enticed toward tranquility. A barefoot maiden in a white tunic serenely emptied her vessel into a basin. Petunias and geraniums in pinks and whites let me know that I was safe. But then behind her: lights! A train was coming, and I was on the tracks. I ran up a ramp to the final hole.

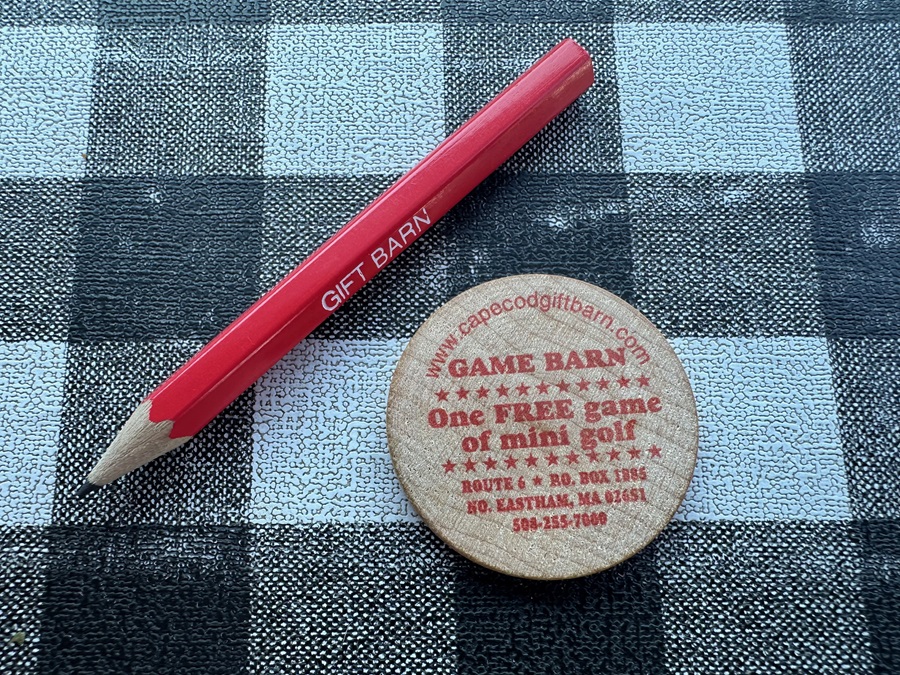

I whacked my ball straight ahead towards something obscured by a wire enclosure. An alarm went off within the Gift Barn; footsteps were heard; a hand emerged from a window and placed a token in my palm. I had hit a hole-in-one. Above me, a sign I had missed: “Ball in Clown’s Mouth wins free pass!”

I listened as my golf ball clunked its way down this creature’s esophagus and decided to let my daydreams go. I headed for the car, tucking the free pass into my wallet. Mini golf, as with the world’s great gardens, is best taken one round at a time.