If you were to picture coral right now, your mind’s eye would surely see tropical reefs with crystal-clear turquoise water. But that image is incomplete: the temperate seas around the world are full of corals clinging to the walls of trenches, rocky cliffs, and seamounts, and the waters around Cape Cod are no exception.

The deep waters of the Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank are home to a vast array of corals. Previous research has revealed their diversity, ecological value, and adaptations. Now, a three-year-long National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) initiative is aiming to shed more light on these animals, which are facing a barrage of threats from human activity that could wipe them out before we even get a chance to understand them.

Meet Your Local Corals

There are two groups of corals in the waters around Cape Cod: those found close to shore, and those found in the depths.

The Outer Cape does not offer much suitable coral habitat for the first, which are found in waters under 50 meters deep, said Peter Auster, research professor emeritus of marine sciences at the University of Connecticut and senior research scientist at the Mystic Aquarium. Corals rely on food carried by water currents, so they thrive best in rocky areas that divert water, forcing currents to flow over them.

Near the rocky areas around Woods Hole, one species is Astrangia poculata, or the northern star coral, whose translucent, grasping tentacles make it look like a sea anemone. It reaches its northern range limit in that area.

According to Loretta Roberson, associate scientist at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, these non-reefbuilding corals can survive attached to anything hard, even something not anchored to the seabed. Roberson described finding “coral rocks,” where a pebble or clam shell gets encrusted in layers of northern star coral, rolling untethered on the seafloor.

There is one species of coral that thrives on the sandy seafloor around the Outer Cape: Pennatula aculeate, a so-called sea pen that looks like a pink feather duster sticking out of the sand. These animals dot the sandy bottoms of the Gulf of Maine, though they do not form colonies like other corals.

To find more corals, you need to go into much deeper water, toward rocky structures in the northern part of the Gulf of Maine or out to the canyons of Georges Bank.

At these sites, the corals get much more dramatic. There are red tree corals, whose orangey fronds sway in the currents; Paramuricea placomus, whose yellow branches spreading upward like an open hand give it the name “fan coral”; and the bright pink tree-shaped creature known as bubblegum coral.

These corals can grow big — upward of 10 feet tall — and their skeletons form walls of habitat that are home to a diverse array of marine life from cod to shrimp to starfish.

One fish that is particularly tied to coral in the Gulf of Maine is Acadian redfish, according to David Packer, a marine ecologist who leads or co-leads all deep-sea coral research activities with the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center. Juvenile redfish hide from predators in the corals’ branches, adults search the colonies for food, and pregnant females take shelter within as they approach their egg-laying time. Nearer to shore, even the tiny sea pens can shelter larval redfish in their fronds.

Massachusetts’s Acadian redfish fishery was valued at $5.8 million in 2022, according to NOAA Fisheries landings data, and some portion of that fishery surely grew up among the branches of the Gulf’s coral.

‘The Trees’ Are Gone

According to Auster, fishermen were the first to understand that there were corals in our waters. Indeed, they had established spots that were known for their coral colonies. Fishermen called one spot on Georges Bank “the Trees,” said Auster, because of the three-foot-long specimens of bubblegum coral they would pull up in their nets.

But it wasn’t until the early 2000s that scientists began using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to observe our northeastern corals in their natural state.

Auster and Packer were among these early researchers, whose surveys culminated in a 2012 to 2015 NOAA initiative that surveyed possible coral habitat throughout the Northeast. That work helped identify some key coral hotspots in the Gulf of Maine like Outer Schoodic Ridge, Mount Desert Rock, and Jordan Basin, all northeast of Cape Cod. It also led to the study of coral diversity in the submarine canyons at the edge of the continental shelf.

Thanks to this research, these areas are protected habitats. On June 25, 2021, NOAA designated the Outer Schoodic Ridge, Mount Desert Rock, and the whole of Georges Bank beyond the continental shelf as “coral protection areas,” where certain bottom-trawling fishing gear is not permitted. Jordan Basin was also designated as a dedicated habitat research area, where the effects of fishing could be studied.

Expanding the Research

Now, 11 years after that last initiative concluded, the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center is undertaking another three-year study of corals from Maine to North Carolina. It began last year and runs to 2026; it will also look at the region’s sponges, which often live in the same habitats.

A group of Canadian and American scientists led by NOAA Research Zoologist Martha Nizinsky are beginning their first research cruise of the project this week, Packer said. They will survey a series of submarine canyons and seamounts at the edge of the shelf before heading into the Gulf of Maine. At any spot they deem could be suitable coral habitat, they deploy an ROV to examine whatever corals are found down there.

Packer said he hopes this research provides the information required to establish an international coral-protected area on the Canadian-American sea border.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is also interested in NOAA’s findings, Packer said. Corals are vulnerable to all forms of seafloor disturbance, so wind turbine construction could cause enormous damage to them. Packer said he hopes the research can ensure that wind infrastructure is installed in coral-free areas.

Big Threats, Slow Growth

Corals in the Gulf of Maine are patchily distributed, in part due to the scarcity of good rocky habitat. But that distribution is also a reflection of years of damage from bottom trawling.

According to Auster, trawl fishing has driven a decline in corals. He said that rubber rockhopper discs on the bottom lip of trawl nets allow fishermen to deploy their nets in rocky environments with less fear of snags — but that puts them directly in the path of corals.

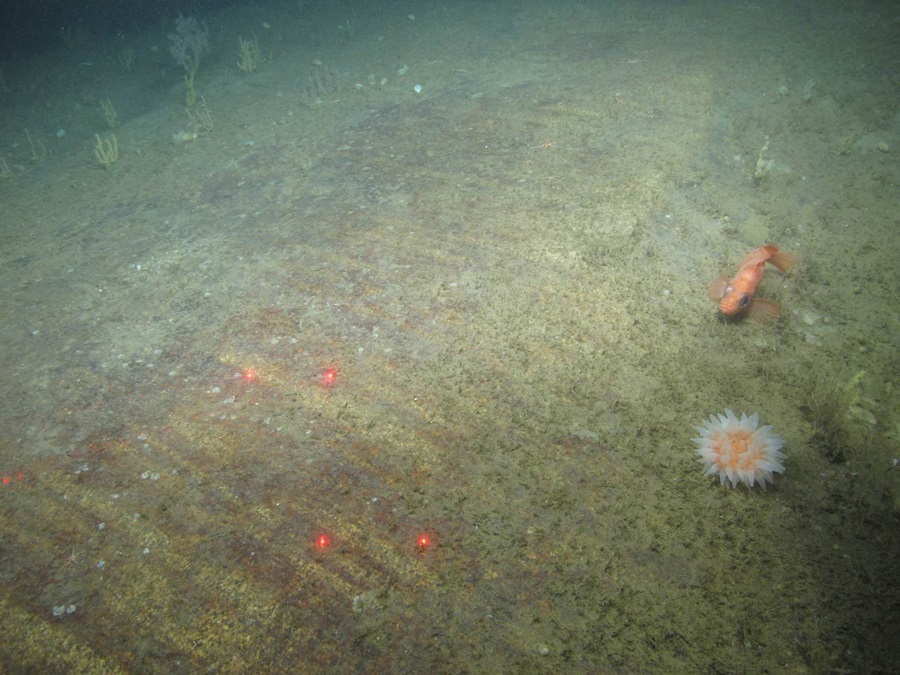

Packer noted that today, in many patches of ideal habitat, corals are found only in the cracks and crevices where trawlers can’t reach them — “the rest of it is just bare rock.” Heavily disturbed coral colonies like this can theoretically regrow, said Packer. But deep-sea corals grow very slowly, with some specimens found to be thousands of years old. At their slow growth rates, “often only a few millimeters per year, damaged deep-sea coral groves won’t regenerate for hundreds of years, if ever,” according to NOAA’s web page on the animals.

Without serious action taken to protect these areas from trawling, Packer said, “we don’t expect them to recover.”

Bubblegum coral has been particularly hard hit by trawling and has declined at a much faster rate than other corals. Packer is not certain why this species seems to be especially susceptible to trawling, but that rich trove of bubblegum coral in Georges Bank that fishermen knew as “the Trees” doesn’t exist anymore, he said.

Fishing is not the only threat to these corals. Ocean acidification can weaken their skeletons, said Packer, making them more susceptible to breakage. Roberson’s research at the Marine Biological Laboratory has also revealed that northern star coral will readily incorporate microplastics into their skeletons, which may make them more breakable as well.

But there may be no greater threat to coral than climate change. It is well understood that a warming climate is the cause of coral bleaching events in the tropical seas, where corals get too hot and expel the symbiotic algae that live in their tissues — algae that in turn supply the nutrients corals need.

In this regard, our corals are lucky — because of the high concentration of nutrients in our waters, they can survive without algae. “You can find colonies that are completely bleached,” Roberson said, “and yet they survive.”

But despite being tolerant of bleaching, our corals cannot survive in warm waters. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 99 percent of the oceans on Earth, said Auster, and some submarine canyons may soon be too hot to support coral.

In light of these threats, Auster told the Independent that action is needed now, even if it means aggressive limits on trawling both where the populations are decimated and where they are still living. Without that kind of change, the corals will soon be listed as endangered, which only comes with more “draconian” rules, he said.