WELLFLEET — Capt. Richard Bailey was fascinated as a child by two oil paintings that hung side by side in his great-aunt’s cabin on Chequessett Neck Road. On occasion, he would sit down and sketch them with his crayons, memorizing the shapes of the two stately tall ships depicted, one a square-rigger barque, the other a three-masted schooner.

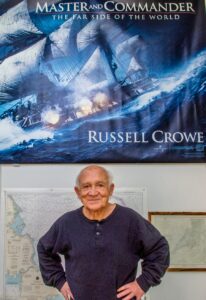

Now retired and settled into his house down the road from his great-aunt’s property, Bailey remembers the paintings as his first encounter with a world that would become a lifelong obsession. Bailey has spent much of his life captaining tall ships, sailing the world with his Jack Russell terriers, and bringing back mementos from his travels. Those include a cat from Cuba, a chicken from the Cayman Islands, and a hefty stipend from captaining a ship for the filming of Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, the 2003 movie which starred Russell Crowe.

Perhaps it wasn’t only the grandiosity of the tall ships in his great-aunt’s paintings that fascinated young Bailey but also something coded in his genome. The ships in the paintings were owned by his great-great-grandfather, Richard Freeman of Wellfleet. Freeman, Bailey says, owned 14 schooners and clipper ships, which he sailed in the Old China Trade — an opportunity that arose after the Revolutionary War and began with the trading of furs, ginseng, and opium for silver.

Two generations later, Bailey’s father, Richard Jackson, took up work as a scalloper on a 44-foot dragger out of Wellfleet. He was lost on an excursion to Stellwagen Bank in the summer of 1950.

“It was theorized he got run down by a merchant ship,” Bailey says. “He was never found, and neither was his dragger.” Only an empty orange dory floating through the foggy water caught the eye of nearby mariners, Bailey says. Six weeks later, Bailey was born.

After his father’s death, his mother sent him to live with his grandparents in Provincetown. Her father, James V. Souza, was a strawberry vendor who sold the fruit on the street.

When Bailey was five years old, his mother remarried, and the family moved to Rhode Island. At age 19, Bailey read in the Providence Journal that a Newport man named John Millar had commissioned a replica of an 18th-century Royal Navy frigate named the HMS Rose, and she was coming to Rhode Island. Two years later, Bailey went to see the 179-foot ship in her berth, looking up at it as he had done with his aunt’s paintings. “I just sat next to it thinking,” he recalls, “how does this exist?”

Bailey became the ship’s dedicated captain after working several seasons as a crew member. He operated it for the next 16 years on charters around the East Coast. He also took her to the Great Lakes and the Gulf Coast, and in 1996 he sailed her to Europe for a series of Tall Ships events in celebration of the 500th anniversary of John Cabot’s first voyage to Newfoundland.

“You either get your career coming through the great cabin windows, or you come up the hawse pipe,” Bailey says about working his way up through the ranks. “I was a hawse pipe guy.”

Millar leased out the Rose as a sailing school vessel for college programs, Boy Scout troops, and school groups, Bailey says. She also got her sails wet for a career in film in 1977 by starring in a Sherwin Williams paint commercial. “Then Hollywood bought the ship,” says Bailey.

That was in the early aughts, when 20th Century Fox acquired the Rose to star in Master and Commander. Millar had called Bailey with the news and told him, “There’s only one condition — you have to go with it,” Bailey says. “So, they sold me with the ship.”

Bailey had to sail the ship to San Diego, where the film was to be shot. In the stretch of the voyage between Newport and Puerto Rico, a giant storm hit. The wind gusts were up to 74 miles per hour, and Bailey navigated the ship through 20-foot waves. “The ship was just plunging up and down, slamming back and forth,” he says. “It started to leak like a sieve. We were taking water through the sides.”

But the crew made it, and it was only later during the filming of the movie that Bailey realized there was a huge crack in the 20-inch-diameter mast. An actor in the film informed him that “the big round thing has a crack in it,” he says. Bailey captained the ship for scenes on the water. And although he didn’t appear in any of the shots, “they dressed me head to toe, put me in makeup, and put these big eyebrows on me,” he says. “It was a blast.”

After shooting was complete, the Rose stayed in San Diego under the maintenance of the Maritime Museum of San Diego. She has returned to the screen on occasion, starring in Pirates of the Caribbean IV and a Super Bowl commercial for TurboTax.

Bailey didn’t return to Hollywood, but he looks back on the experience fondly. “Hollywood was good to me,” he says. “It worked wonders on my Social Security. Nice work if you can get it.”

Bailey returned to Wellfleet, where he built a house with the money he earned from the movie. But he got antsy and returned to captaining schooners.

One ship took him to Cuba in 2016. While he was there, Fidel Castro died, and the crew’s plans to buy liters of rum were dashed by a country plunged into mourning. “There was no dancing, no music, no liquor sales,” he recalls. “But we found a guy.” The crew smuggled the rum out of the country along with a six-week-old kitten named Pilar that had appeared on the boat.

Bailey still sails for a couple of weeks a year on the barquentine ship Gazela Primeiro, but those longer voyages are for the most part over. According to Marine Vessel Traffic, there are currently 79 tall ships in operation across the world.

In his retirement in Wellfleet, Bailey has developed a sound routine, which at this time of year includes a daily trip to the post office before taking his terriers to count herring off Black Pond Road. Bailey has been doing the counts, which occur between April 1 and June 30, for the past dozen years. “I’m not much of a scientist, but I like to be a good citizen,” he says.

He also spends his days researching the French-derived word “kumetage,” which he hopes to persuade the Oxford English Dictionary to include in its next edition. “There is enough evidence of its longevity in English for it to be included,” says Bailey.

American mathematician Nathaniel Bodwitch, known for his work on ocean navigation, defined the word in his 1837 book The New American Practical Navigator as “a bright appearance in the horizon, under the sun or moon, arising from the reflected light of these bodies from the small rippling waves on the surface of the water.”