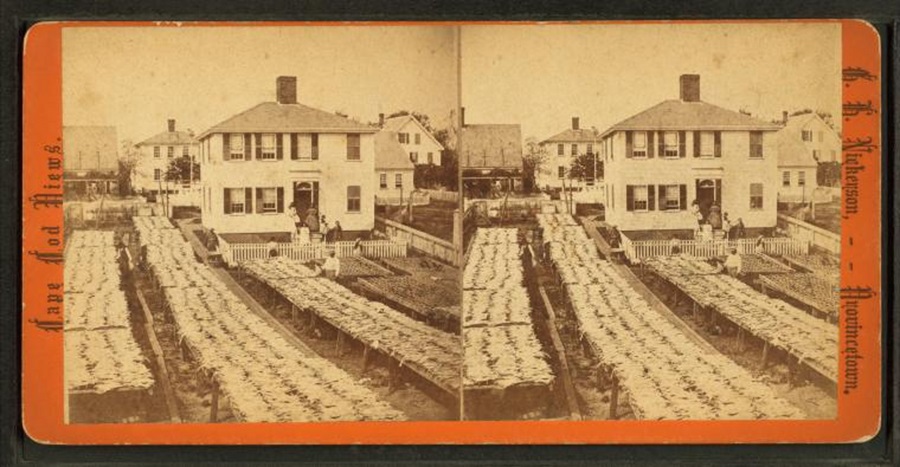

In 1851, a single vessel carrying 44,000 codfish docked in Provincetown, as some fish house employees told Henry David Thoreau, according to his 1865 travelog Cape Cod. A fish house was where people pickled cod, the sort of reeking place that made Thoreau — a man not easily fazed — lose his appetite.

“One young man,” he wrote of his encounter at the fish house, “spat on the fish repeatedly.” That man’s boss does the same and Thoreau swears to never take a bite of the food.

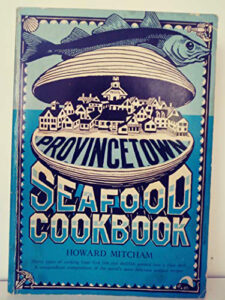

Also known as “scoodled skulljoe,” or “skully-jo,” salt cod was Provincetown’s most popular product for nearly a century, according to Howard Mitcham’s 1975 Provincetown Seafood Cookbook, though in the 19th century the majority of people who ate it were not locals but people enslaved on sugar plantations in the colonial British West Indies. It was protein-rich, it was long-lasting, and it was cheap. When slavery was abolished in the British West Indies in 1843, salt cod began its century-long decline. Yet as demand on plantations declined, it grew in the North: salt cod was the food that fed the Union Army.

M.C.M. Hatch, a railroad engineer and Provincetown octagonal home-dweller, declared his bitter hatred of the stuff in his 1939 The Log of Provincetown and Truro on Cape Cod. “As food, it had the merit of permanence,” he wrote.

A skully joe maker faces challenges on today’s Cape. For one thing, most cod sold here comes from Iceland. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration prohibited cod fishing north of Provincetown 10 years ago, to the dismay of many cod fishermen who insisted that there were enough cod, depending on where you look and what counts as enough. NOAA says that cod stocks are at less than 5 percent of a sustainable level; fishermen say that, since 2013, cod populations have increased.

Committed to finding an authentic Cape Cod fish, I was told that my best chance was folding my hands and praying that some fisherman would accidentally catch one. The winds weren’t right, one fisherman told me. Chris King, owner of Cape Tip Seafood and the descendant of a long line of cod fishermen, said the odds I’d find a local cod were slim to none, but he would keep an eye out.

Then, one bright morning, King sent a message: “We are in luck.” The cod he’d acquired weighed 25 pounds. I wondered if that three-newborn-baby size was too big for my project (my recipe called for two pounds), but King insisted that this was the weight of fish typically used. I drove to his warehouse and knocked on the door, and a man named Chad led me to the fish, which was sitting on ice in the corner of the otherwise empty room. I put it in the trunk of my car.

The fish had come off the south coast of Cape Ann, King told me, beyond the Stellwagen Bank, a marine wildlife sanctuary. Wikipedia tells me that in the 17th century fishermen were overjoyed to find large cod in that same area. I had procured historically accurate cod.

Once the cod was lodged in my refrigerator, amid half-used cans of chickpeas and three different cartons of oat milk, I felt rather proud of myself. That prideful glow was short-lived, however: I told my editor about my acquisition, and she asked me if the fish was fileted, which it was not. I figured I would do it myself. Suddenly she was on the phone telling Josiah Mayo that she had a writer who was trying to butcher a huge cod “by stabbing it with a butter knife.” She had a point. I took the fish to Mac’s, where a professional monger named Jason Cutrell did the doing.

I intended to follow the recipe for skully joe in Mitcham’s beloved cookbook, the one with the Anthony Bourdain introduction. Like a wise spirit from 1975, Mitcham warned me that making this delicacy was not for the fainthearted. I ignored his warnings. I thought I knew something of fermentation, having brewed ginger beer in my childhood bedroom and later mead in my college dorm. But I soon learned that those Cape Cod fishermen of old were up to something far more serious.

As directed, I filled a basin with water and dumped enough salt in it to make a medium-sized potato float. With my brine ready, I placed my fish in the pot for 24 hours. Now, as I write this, I realize that the amount of salt Mitcham recommended was intended for a fish four-hundredths the size of the fish I’d obtained. But after the 24 hours, my trusty colleague William von Herff placed one half of the fileted cod in the fridge; then, for a historically accurate simulation of the elements, he put the other half in his back yard.

In summer, I suppose, sea spray and harsh sun would quickly wear the salted fish down to a hard husk. But it was November and sunlight was declining rapidly, so we did the best we could, positioning the fish directly in the sun and praying for wind. I did not hang it on the clothesline because we are among those lucky enough to have a washer-dryer in our apartment.

The drying of the cod coincided with Thanksgiving, and I had to return home to New York, so I left it to Will to tend in my absence. Five days later he sent a photo of maggots on the cod we’d put outside.

My hubris had come in part from the countless sources that described salt cod as a treat suitable for children. “We’d eat them instead of candy,” Floran Menangas Rozzelle wrote of sticks of salt cod she recalled from her Portuguese-American childhood in Provincetown. “It made an all-day sucker look as ephemeral as a marshmallow,” Hatch wrote.

Coming home to tend my “fisherman’s candy,” I was greeted by the smell of rotting fish stinking up the fridge. My roommates insisted I see the pickling through, but I knew something was wrong. The cod was supposed to have bloated with salt intake but, from what I could tell, it hadn’t. I hauled it out of the fridge, and my roommate, who had agreed to try my skully joe, recoiled at the stench. This was no salt cod. This was just spoiled fish. A sacrilege.

As a backup I had layed in a pound of professionally rendered bacalhau from Portugalia Market in Fall River. I would have to count on it for an approximation of the taste of P’town past. Michael Benevides, the manager at Portugalia, told me that families from up and down the East Coast will travel hours to buy a case of salt cod at the market. There, they have a whole room dedicated to the food.

Strangely enough, after going to all that trouble to salt it, one has to desalt the cod before cooking it. After two days of freshwater baths for the cod, I cooled down a can of Narragansett in preparation for frying some up because Mitcham warned me that “IT TASTES SO GOOD WITH BEER. It’s ten times better than potato chips, or salted peanuts, or fried pork skins and other thirst-provokers that are foisted off on us beer guzzlers.” I would not, could not ignore his all-caps the way I’d ignored his other warnings.

After days of smelling rotten fish, I’d come to worry about my future with skully joe. But here it was, a little saltier and tougher than fresh fish. But with beer, it tasted like summers long past.