The cold season has its own aesthetics. Bare. Subtle tones. Grays, browns, tans, blacks, the dormant green of pines. Blue air at dawn and dusk. The sky and ocean wearing the same stormy shades and roiled textures.

The winter forest is filled with emptiness. The leaves have done their work and lie in wet layers on the ground. Everything moves unhindered through the woods now. Sunlight, pale and angled low, reaches the fine thin branches of the huckleberry.

This season, too, has its sounds. The wind through twigs and trunks. A single ocean wave, an hour’s walk away, cracks the cold air like a rifle shot. And in the night, a sound gentle and forceful at once — the voice of the great horned owl.

I often wake on winter nights to the call of an owl. The sound draws me from sleep and pulls my thoughts out into the cold and dark. I open the window and prop myself up, arms resting on the sill, eyes closed. I listen. My mind out in the night, high in the naked, brittle branches. A call comes from deep in the woods and pours through the open space like liquid. Sometimes it sounds lonely, mournful. Sometimes there is an answer. If the winter night were to make a sound, it would be that of the owl. Hollow. Patient. Fearful, yet comforting.

In many cultures, owls are believed to be a connection between the physical realm and the spiritual. They are like spirits themselves: mysterious, ever present, watchful, and rarely seen.

The owl, for me, is my grandmother. She had a collection of owl figures. Shelves crowded with hooked beaks and watching eyes. My mom always told me her mother would speak to her and visit her in the form of an owl after she left us.

On a purple winter dusk, years ago, a great horned owl dropped down from a tall stand of pines through the openness of the woods. It swept just over my head and into the woods — a big, dark body, more shadow than physical thing. As she bent her weight against the air on wide wings, there was a rushing silence. It was an absence of sound, a void into which all sound was drawn and carried off. Sound’s equivalent to pitch black. That is what I remember most about her visit.

Large wings let the great horned owl fly slowly. The leading edge of the owl’s wing has a comb-like serration that slices through the air, grooming turbulence into streamlined airflow. The trailing edge of the wing is a fine, velvety fringe that dampens any texture still left in the air by the forward edge. The owl’s flight creates silence.

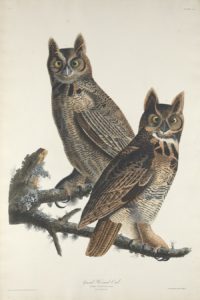

The horns that give this owl its name are not horns at all. Tufts of feathers sit high on its head; what purpose they serve is a mystery. These are often mistakenly identified as the owl’s ears. But its ears are set further down, in asymmetry, the right ear just a tad higher than the left. This adaptation staggers the sounds that reach the owl, allowing it to pinpoint a mouse rustling in the underbrush. As the owl swoops down, the silence of its wings lets it hear as it floats toward its prey. The mouse hears nothing.

Owls call into the cold night to declare this place their home. “This forest and all the sounds within it belong to me.” Each owl claims a territory over a mile across. And they call out for their lifelong mates. “I am here. Where are you?”

On a still winter night, a call rolls out through glass-thin air. It fills the dark space. Under the heavy, cold oak branches. Into the void over ponds, still as a mirror, full of stars. Into a window drawn open. With its wings, an owl returns the sound it has gathered back to the night.