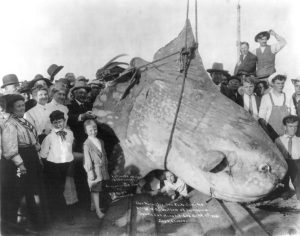

WELLFLEET — After a mysterious flopping in the water, a large dorsal fin emerges. You think: “shark!” But it turns out to be an ocean sunfish, Mola mola, leisurely swimming near the surface. These fish are among the strangest creatures our ocean has to offer. They are the heaviest bony fish in the world and can weigh a ton or more.

These unusual-looking animals typically migrate south to their overwintering grounds by the end of summer. But warming waters and an abundance of jellyfish — they have a predilection for the gelatinous invertebrates — mean that some are remaining here until fall and early winter. If they remain in New England for too long, as the water temperatures drop, they can become victims of cold-stunning, just as sea turtles do.

Ocean sunfish got their common name because they are often observed basking or sunbathing on their sides. They are found globally in tropical and temperate waters and it is speculated that this behavior helps them regulate their body temperature, warming them up after deep dives for prey. It may also be that this basking allows birds to pick off some of the multitudes of parasites that cover them.

Part of what makes these fish look so odd is their lack of a tail, so they have also been nicknamed “swimming heads.”

Recreational boaters have seen many ocean sunfish in Cape Cod Bay and Wellfleet Harbor this year, and now, some of them are not making it safely to the south before they collide with boats, get entangled in fishing gear, or, more often, get trapped in low water during the Cape’s massive tides.

No one knows how long it takes molas to reach their adult weights or how long they live. They are not a commercially important species, except in some Asian countries where parts of them are eaten. Very little is known about the distribution, diet, and behavior of ocean sunfish in New England. Carol “Krill” Carson, of Middleboro, founder and president of the New England Coastal Wildlife Alliance (NECWA), initiated a program to learn more about them.

In 2005, Carson set up a “community sighting network” to get boaters, fishermen, and beachgoers to report sightings of sunfish offshore. Carson says she didn’t expect to receive reports of sunfish struggling in shallow waters or dead along the shore.

Team Mola is the Alliance’s volunteer network, with members trained to respond to mola sightings. An Oct. 13 report in the Boston Globe made clear that contacting Carson’s group when you see a mola is preferable to calling the police. In Wareham, local police received so many calls about a mola sighted in a cove that the town’s natural resources officer had to put out a notice on social media advising people that the animal was fine, and just “doing normal sunfish activities.”

Volunteers get calls to action via an app, and, during the first week of October, cell phones were pinging constantly with text messages indicating the locations of stranded fish. Carson and her volunteers fanned out from Brewster to Provincetown to assess the situations, document strandings, help animals get back to the water, and collect data and tissues from carcasses. Carson sends mola samples around the world to scientists who are studying these animals.

Mola volunteers are a special breed. The fish they work with is not particularly charismatic, nor is it considered threatened or endangered. Many of the same volunteers are also trained to respond to marine mammals and sea turtles. Outer Cape Mola team members Seth Cohen, a former middle school science teacher, and Nick Picariello, a retired physician (and this writer’s husband) both say they do the work because they enjoy learning about Cape wildlife and contributing to scientific knowledge.

Firefighter-paramedic Holly Kuhn says that Carson’s “energy and enthusiasm are contagious.” A pivotal moment for Kuhn happened when she saw a mola swim into shallow water near Mayo Beach in Wellfleet. Over the phone, Carson encouraged Kuhn to put on gloves, wade in, and push it back. “Being in the water with this giant, gentle, crazy-looking fish was mesmerizing,” Kuhn said. “And just like that, Krill had a new team member.”

Members of Team Mola are not averse to long walks on the beach, even in foul weather, nor to the unique odor of a rotting carcass that will lead them to the specimen they seek. Volunteer Hal Levine, a former professional geologist, is surprised when other beach walkers “don’t even ask what we are doing,” as they examine the dead fish.

When it’s feasible, the carcasses are weighed with a special apparatus that must be transported to the stranding site. Some of the larger Cape Cod specimens have topped 1,400 lbs. Rescues of live animals, when they are sighted in the shallows, consist essentially of pushing them into deeper water in hopes that they won’t wash up on a beach or marsh during the next low tide.

If you see a Mola mola, please file a report at nebshark.org, or call the mola hotline: 508-566-0009.

Barbara Brennessel is professor emerita at Wheaton College and a Team Mola volunteer.