The passing of Labor Day marks the end of our cut-pad-on-an-oyster-shell season and the beginning of the itchy-dog-and-cat season here on the Cape. (This will be followed by pancreatic inflammation season and then, promptly, by toxin ingestion season.)

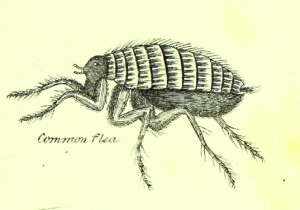

Late summer and early fall is typically when most animals who seasonally itch will start licking, rubbing, and scratching. Chronic itchiness in animals, usually well controlled, will acutely flare up. For a significant number of pets, this is the result of peak flea season arriving on the Cape. Fleas are the number-one allergen observed in dogs and cats worldwide, mostly the “cat flea,” which affects dogs, cats, and people.

I know what you are thinking. I hear you saying it. It’s not fleas. I don’t have fleas.

I am here to say it publicly to everyone: it’s OK to be allergic to fleas and to share the environment with them. It’s even OK to have fleas. Symptoms of flea allergy, however, do not necessarily mean you have fleas; it just means your allergic pet has been bitten by one.

Fleas have been found on prehistoric creatures from 60 million years ago. They are here to stay and enjoy the Cape like the rest of us. They are found in dog parks and kennels, on wildlife and stray animals, and in that cool, shady hole your dog dug up under the porch. One flea bite is enough to cause hypersensitivity in animals. About 15 percent of animals will have no evidence of fleas on examination, and yet it is still flea bites triggering the itch response.

We routinely check for flea dirt by combing at the base of an animal’s tail. By knocking any debris you gather on a white paper towel, adding a little water, and crushing the material, you can identify flea dirt by the streak of bright red or rust color that appears. This is digested blood, a.k.a. flea dirt, a.k.a. flea poop.

In dogs, flea allergy hypersensitivity will cause significant itching, mostly on their hind end, legs, and belly. In cats, it will often cause a generalized skin infection, but most frequently hair loss on the back and lower half of the body. Since cats are such fastidious groomers, most will have no evidence of fleas (and they take great pride in that). That overgrooming, removing every speck of flea dirt, however, can cause a skin infection and vomiting due to hair balls.

Yes, your indoor overgrooming cat can be exposed to fleas. Fleas do not respect boundaries and will come in through screens and riding on rodents. The positive thing about a flea allergy is that it is treatable with safe and effective pesticides. Vacuuming and washing bedding will also help stop the itching, as will treating any secondary infection that may have developed.

Treating year-round for fleas, even your indoor cats, is important, not only to improve their quality of life by itching less, but because of zoonotic diseases such as cat scratch fever. Yes, that’s not just a Ted Nugent earworm, it is a real disease, spread to humans by flea dirt in an infected wound.

To learn more by watching creepy videos of parasites, check out the Companion Animal Parasite Council (capcvet.org) and petsandparasites.com. Maybe you can even get a head start on a horrifying Halloween costume.

Sadie Hutchings, D.V.M., practices at the Herring Cove Animal Hospital in Provincetown.