PROVINCETOWN — Everybody knows the name Tennessee Williams, the two-time Pulitzer-Prize-winning playwright who gave us The Glass Menagerie, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and A Streetcar Named Desire.

Not everyone knows the name Yukio Mishima, a Japanese author who was thrice considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature, though he never won.

Very few know the two men were friends. But Mishima had a major impact on Williams’s career, and that may have been a factor in the difficulties he faced late in life.

Williams and Mishima were among the most important writers of the 20th century, and both are listed in “The Gay 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Gay Men and Lesbians, Past and Present,” a 1994 book by Paul Russell.

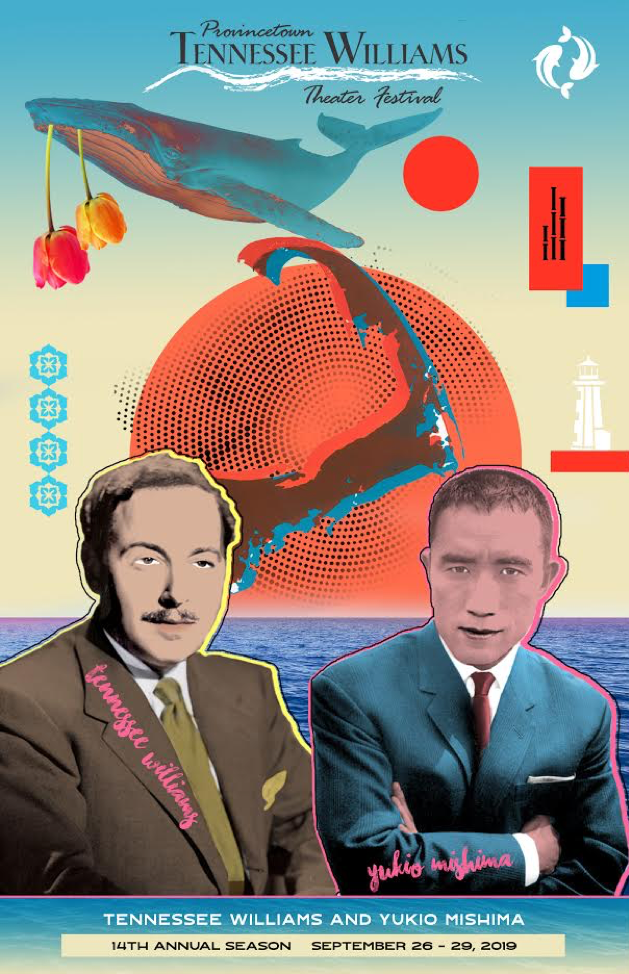

Later this month, the Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival, now in its 14th season, will offer plays by the two friends in exciting presentations that will spotlight the influence that Mishima had on Williams.

“There is a fascinating story here about how queerness can facilitate a truly generative exchange between two writers across otherwise huge barriers of social isolation and cultural difference,” said Keith Vincent, who teaches Japanese literature and queer studies at Boston University as chair of the Dept. of World Languages and Literatures.

This year, in Provincetown, “We want to give Mishima the same stature as a playwright we would give any other playwright, to show this is worldwide, and resonant now, in a time that lacks a moral certainty,” David Kaplan, curator and co-founder of the festival, told the Independent. “The season seems esoteric, and serious, but it’s also very playful and very funny. A camp sensibility is something that Williams and Mishima had in common.”

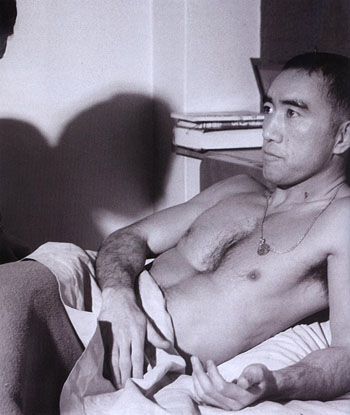

Mishima was a prolific author and a larger-than-life figure in Japan’s postwar literary scene. Born in 1925, he wrote 34 novels, 50 plays, and numerous essays and short stories. In the 1950s, as Japan rebuilt from the devastation of World War II to become an industrial powerhouse, Mishima became a right-wing nationalist, bodybuilder, and enthusiast of kendo, which is traditional swordsmanship practiced with wooden “blades.” He recruited a private militia of about 100 members, and in 1970 he and a small group of followers barricaded themselves in the office of a military commander, where he committed suicide in dramatic samurai fashion, with the coup de grace executed by one of his men.

But that is getting ahead of our story. In the 1950s, Mishima was enamored of Noh, a traditional, courtly form of theater that is very slow-moving and abstract. He wrote a series of works that were published in English translation as “Five Modern Noh Plays.” He traveled to New York in hopes of staging an off-Broadway production.

One Saturday night in 1957, recounts author John Lahr in Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh, Williams threw a party at his Manhattan apartment (“something of a sin bin”), and picked up Mishima on the street, apparently not realizing at first who he was. In the ensuing years, the two men met many times, both in America and in Japan. Over time they shared an agent and a publisher. On May 8, 1960 they were interviewed by Edward R. Murrow on the CBS television show “Small World,” Williams speaking from Key West and Mishima from Tokyo.

“Mishima and Williams really influenced each other’s work,” Kaplan said. “Mishima was encouraged to learn about Williams breaking genres, interrupting lyricism, trying to create theater that would express the lack of a moral center, a lack of certainty that was common to both Japan and America after World War II.”

One of Williams’s plays from 1960 was titled The Day on Which a Man Dies, an Occidental Noh play dedicated to Yukio Mishima, and his A Night in a Bar in Tokyo was inspired by their friendship. Several of Williams’s plays from the 1960s on incorporate elements of Japanese theater such as Noh-inspired staging, as well as characters derived from the kuroko of Japanese theater, the “onstage stagehands” dressed in black who assist the production while hiding in plain sight.

“Williams’s interest in Asia was intrinsic in his training, his education, and his personal taste,” said Kaplan. “It was not a matter of exotica. It gets to the core of his work, and what interested him as a person and an artist. Even back in A Streetcar Named Desire [1953], there’s a reason why Blanche puts a paper lantern on the light bulb.”

But from about 1960 onward, as Williams grew more interested in Japanese theater and used more of its unfamiliar elements in his plays, his popularity sagged. This may have had to do with alcoholism or other personal issues, but some scholars say his late style was simply too adventurous for the American public.

“Williams was getting at something deeper in these later plays,” wrote Sarah Elizabeth Johnson, a Williams scholar. “In his search for a dramaturgy to support these deep discoveries, he had to look halfway around the world in a culture very different from his own.”

This year, the Provincetown festival is presenting four plays by Williams and four by Mishima, including the world premiere of one work by each playwright. Performances are at the Provincetown Theater, 238 Bradford St.

In just four days, from Sept. 26 to 29, the festival is presenting nearly 70 events, including several performances of each of the plays, a master class with Kathleen Turner, a symposium on Williams, workshops on traditional Japanese theater — Noh, Kabuki, Kyogen, Kami-Shibai — and of course parties and mixers. The actors and theater companies are from all over the world. A summary of the offerings follows.

Kathleen Turner Master Class — Turner has won two Golden Globes and been nominated for the Tony and Academy awards.

Busu (Mishima, world premiere) — “Temptation gets the better of two panicked shop assistants in a madcap physical comedy, followed by a traditional Japanese version of the same story.” Directed by Daniel Irizarry and Laurence Kominz, translated by Donald Keene and Laurence Kominz. One-Eighth Theater and Portland State University Kyogen.

The Lady from the Village of Falling Flowers (Williams, world premiere) — “The power of poetry seals two strangers’ fates in this charming one-act romance set in ancient Japan,”

directed by Natsu Onoda Power, Spooky Action Theater of Washington, D.C.

The Lighthouse (Mishima, English-language premiere) — “Unspoken desire breaks the surface of a post-war family’s placid life.” Directed by Benny Sato Ambush.

The Night of the Iguana (Williams) — “South African and American artists stage Williams’s vision of madness, endurance, and grace in a new production inspired by Japan’s traditional Noh theater.” Abrahamse and Meyer Productions, from Cape Town, South Africa.

The Black Lizard (Mishima) — “An unexpected cultural collision of camp, film noir, drag queens, and the Sherlock Holmes of Japan, and a playful play about illusion.” Directed by Jesse Jou, featuring Yuhua Hamasaki, in association with Texas Tech University.

And Tell Sad Stories of the Deaths of Queens… (Williams) — “A New Orleans queen brings a rough sailor into her garden.” Directed by Lane Savadove. Egopo Classic Theater of Philadelphia.

The Lady Aoi (Mishima) — “An apparition haunts a hospital bed in this modern version of an ancient Japanese Noh play.” Performed with puppets, masks, and live actors. Abrahamse and Meyer Productions, from Cape Town, South Africa.

The Angel in the Alcove (based on a short story by Williams) — “A former boarding-house tenant recalls his strange company in this gritty elegy.” Poreia Theatre Group of Cyprus.

Yuhua Comes to Town — “Solo show by Yuhua Hamasaki: drag queen, seamstress, dancer, comedian, and star of The Black Lizard.”

Songs I Learned From My Grandmother — “Composer and pianist George Maurer leads Festival artists, music ranging from hymns to Japanese folksongs to Maurer’s new settings of poetry by Williams, Mishima, and Rilke.”

Williams 101 — Brush up on your Tenneessee Williams knowledge with Patricia Navarra of Hofstra University.

For a complete schedule of Festival events and tickets see twptown.org.