TRURO — Valentina Cook-Wheeler isn’t one to talk about herself. But she does have some stories to tell. Although she lives in Truro now, she is not only a third-generation Provincetown native, she is third-generation Cookie’s Tap. Joe Cook’s daughter, she is a preserver of recipes and history from Provincetown’s fabled West End restaurant.

Around 1875, Cook-Wheeler says, her great-grandfather, Manuel de Faria, left São Miguel — an island in the Azores archipelago — for Massachusetts. He was one of hundreds of young Portuguese men whom Yankee captains recruited for their fishing crews, offering the Outer Cape as a land of boundless opportunity. Manuel took a job as a whaling vessel’s cook and landed in Provincetown.

As Tina tells it — there is more than one version of this story — Manuel discovered here that the rolling vowels of “de Faria” made him an outsider. So, he took his occupation as his name and became Manuel Cook.

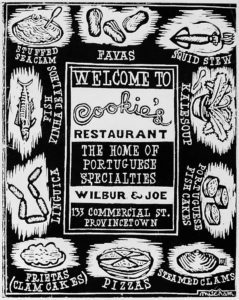

Manuel married and had children. Whaling gave way to fishing. Provincetown’s Portuguese population boomed. And Manuel’s son Frank, known as “Friday,” saw a business opportunity. It was 1934, according to David W. Dunlap’s Building Provincetown, when he bought the store at 133 Commercial St. He redid the floors, set up a bar, and named it Cookie’s Tap. Thus was born an institution.

“You know Ellis Island?” asks Cook-Wheeler. “How everyone went through there on their way places? That was Cookie’s, for the Portuguese.”

For more than 50 years, the restaurant and barroom served as a first stop for newly arrived young Portuguese fishermen — all male, most without a word of English, all trying to find their footing in a three-mile-long town. With its decorations of whalebones and Barcelos roosters and its constant stream of Portuguese chatter — “The hand gestures!” remembers Cook-Wheeler, “the screaming! The fights!” — Cookie’s seemed to its patrons a reimagination of home, a slice of familiarity in a new, alien world.

Its value was practical as well as sentimental. The Tap’s owners through the years, all members of the Cook family, had a longstanding deal with local fishermen. In exchange for a day’s haul of lobsters, scallops, flounder, or crabs, Cookie’s would provide each man with a dinner of a few drinks, squid stew, and a stuffed sea clam.

“They didn’t want the scallops or lobsters,” says Cook-Wheeler. “What they wanted was squid stew.”

Cookie’s was an establishment controlled, it seemed, by men: Friday and, later, his sons, Wilbur, “Philly,” and Cook-Wheeler’s father, Joe. Men staffed the bar, sat at it, drank at it. But from her kitchen next door, Clara Cook, Friday’s wife and Cook-Wheeler’s grandmother, sustained them all.

“Some of my most treasured memories,” says Cook-Wheeler, “are of cooking with my Nana. She’s the inspiration for everything I do.”

The smell of fresh massa sovada — Portuguese sweet bread, an airy brioche-like loaf — coaxed Tina into Clara’s kitchen early on. And once she was in, she was hooked. “I pretty much lived there, watching her,” says Cook-Wheeler.

Clara made Cookie’s garlicky fava beans, squid stew, Portuguese fish cakes, and loaves and loaves of sweet bread. Her recipes were written nowhere, passed down through the generations. Often, she’d scoot her granddaughter out of the room to add a secret ingredient. Tina would spy on her from around the doorjamb, taking mental notes.

“Traditional cooking was her passion,” says Cook-Wheeler. “It became mine, too. She wanted to carry on Portuguese tradition, and I wanted to be with her.”

Cook-Wheeler began making pizzas in Cookie’s kitchen at age 12 and just kept cooking. She was one of the few women tolerated behind the bar. When she had her daughter, Melissa, in 1980, she propped the baby up in the kitchen and enlisted her help as a taste-tester. By three, Melissa was a squid stew expert.

As the fishing industry slowed down, so, too, did Portuguese immigration to Provincetown. Where before had sat young fishermen bickering over mainland versus island Portuguese dialects, there now sat poets, writers, painters.

Howard Mitcham, the cook, artist, and raconteur, was a squid stew aficionado — “Taste isn’t all pretty pictures in Gourmet magazine,” he once told the New York Times food writer Molly O’Neill. “No wonder Mitcham more or less moved in,” writes David Dunlap in Building Provincetown. Mitcham stashed his manuscripts at his regular spot at the restaurant.

“As more painters and writers came to Provincetown and to Cookie’s,” says Cook-Wheeler, “and as more people came out, like my brother, it just became more and more alive. We started with very loud Portuguese people. And it turned into artists, peace-loving and accepting and beautiful. To watch that was amazing.”

Cookie’s was sold in 1987, Tina recalls. “There were no more Portuguese coming,” she says. “I haven’t seen new people in — I don’t even know how long.” While it was heartbreaking, she remembers, to see the restaurant go, what it represented has not disappeared.

Cook-Wheeler kept on cooking. First, with her daughter; then, with her granddaughter, Ava, now 13. “My granddaughter is one of the best cooks,” she says. “She outdoes me with everything. She loves it, and she’s good at it, and she cares about the tradition. And she loves spice.”

The restaurant’s stories and favorite recipes live on in Welcome to Cookie’s: The Home of Portuguese Specialties, a cookbook Cook-Wheeler put together for the annual Portuguese Festival four years ago.

“These are our roots,” she says. “Provincetown is so different, and I love it for that — I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. But it’s important to remember the old times.”

Massa Sovada

This is a home baker’s version of the Portuguese sweet bread Tina’s grandmother Clara made in batches based on 5-lb. bags of flour. Its long rising times are due to the high quantities of sugar, butter, and eggs, which slow the yeast’s action.

1 envelope yeast, about 2 tsp.

1/2 cup warm water

1/2 cup milk, scalded

3 to 3½ cups flour

3/4 cup sugar

1/2 tsp. salt

4 Tbsp. butter, melted

3 eggs, beaten and set aside

1/2 tsp. vanilla

An additional egg for brushing on the loaf

Let the eggs reach room temperature. Scald the milk and set it aside. Melt the butter and set it aside. Sift 3 cups of the flour, sugar, and salt together into a large bowl. Proof the yeast — sprinkle it over the 1/2 cup of warm water to dissolve and bubble.

Beat the eggs and vanilla and stir into the flour mixture. Stir in the melted butter and the scalded milk.

Add the dissolved yeast to the mixture — at this point, Tina plunges clean hands into the dough to combine it well. The dough will be sticky; if it seems too wet, add a little more flour to make it manageable.

Cover the dough with a clean kitchen towel and let rise until it doubles in size — this could take as long as 6 hours.

After the dough has risen, gently punch it down and let it rise again by setting aside for about 4 more hours.

Shape the dough into a round loaf, rest it in a lightly flowered pie pan, and let it rise a third time for about one hour while you preheat the oven to 300 F.

Beat one more egg in a small bowl and use a pastry brush to paint the top of the loaf with it.

Bake about 45 minutes at 300 degrees, until the loaf is golden brown. Butter the top when the loaf comes out of the oven.

Lulu Guisada

Cookie’s squid stew has by now been adapted by many great cooks, from Howard Mitcham to Anthony Bourdain, and probably by Tina’s daughter, Melissa, who had opinions on it from the time she was a toddler. “She loved squid stew,” Tina says. “She would tell me, ‘More peppers, Mom,’ or ‘Just right.’ ”

This recipe combines Tina’s method with a few others. We saw some interesting secret ingredients out there, like Worcestershire sauce (for umami) and poblano peppers (for heat and smokiness) — but haven’t yet strayed that far. Maybe later this squid season.

1/4 cup olive oil

2 sweet onions, chopped

3 cloves garlic, minced

1 tsp. red pepper flakes

3/4 cup sweet vermouth

1 small can tomato paste

1 large can crushed tomatoes

4 pounds whole fresh squid, cleaned

6 potatoes, diced

Salt to taste

Sauté the onion and garlic in a heavy pot and continue cooking slowly over medium heat for a half hour to caramelize and concentrate their flavor. Add the crushed hot red pepper to taste.

Stir in the vermouth, tomato paste, and crushed tomatoes. Simmer the base while you clean the squid and slice it into rings. When you prep the tentacles, be sure to remove the beaks.

Add the squid to the onion, garlic, pepper, and tomato base. Season with salt. Add water just to cover and cook the squid about a half hour. Wash and dice the potatoes and add them to the pot, simmering until they are just tender. Taste and correct for spiciness and salt.