Many might remember the anxious feeling of being urged by a well-intentioned parent to perform for relatives at a family gathering. For Martha Atwood of Wellfleet, the family gathering was the town’s annual Strawberry Festival, at which her mother insisted she sing. The story goes that Martha was reluctant to sing “in front of all those people,” but tearfully gave in to her mother’s prodding and sang a ditty about strawberries appropriate to the occasion. Who could have imagined that the apprehensive Martha would one day sing — in front of all those people — at the Metropolitan Opera?

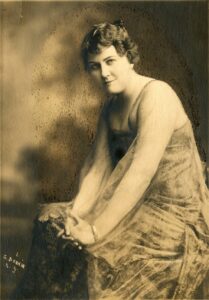

The daughter of Wellfleet native Capt. Simeon Atwood and Martha Ann Burpee, Martha was born in 1886 in Boston. Ill health had forced her father to give up his Wellfleet fishing vessels and relocate to Boston, where he was engaged in the wholesale oyster business. But the family’s ancestral roots and heart were always in Wellfleet, and every summer they returned home. Martha’s precocious vocal talent was encouraged and nurtured both in Boston and in Wellfleet where her “bird-like soprano” became much sought after for church concerts and local events. Her musical education eventually took her to Europe, where she studied for five years in Verona, Milan, and Paris.

In 1923, Martha made her operatic debut in Siena in Puccini’s La Boheme. In 1926, she joined the Metropolitan Opera, making her debut in New York on Nov. 16 of that year in the role of Liù in Turandot, Puccini’s last opera, left unfinished at his death in 1924 and completed by Franco Alfano. The Met production, the first in the U.S., was hailed as “truly splendid.”

After the New York premiere, the Met company performed Turandot in Philadelphia on Nov. 30. A reviewer noted that Martha’s Liù “is lovely and graceful, and she sings the difficult music of the part, which lies very high, fluently, though with upper tones which at times seemed rather shrill.” Later reviews praised Attwood (as she was billed) who “softened the edge of her Liù’s inadequacies and gave a sympathetic reading of the music,” and who sang a “suave-voiced and temperamental Liù.”

Martha’s Metropolitan career also included the role of Nedda in Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci, as well as concert appearances. Her last performance was at a gala concert in January 1930, after which she sang exclusively on radio. By 1936, Martha was pursuing an ambitious dream she had had for decades — the founding of a music school on Cape Cod. She especially hoped to impart the love of music to schoolchildren, no doubt remembering how her earliest studies and the support of the community had shaped her path.

After engaging sponsors and undertaking fundraising benefits, Martha leased an estate in Osterville in May 1937 to serve as the school’s home for the first year, offering “young musicians and artists the opportunity for study, recreation and relaxation in the quiet, quaint atmosphere of Cape Cod,” according to a report in the Hyannis Patriot. Two years later, Martha purchased the old Crosby estate in Brewster as the school’s permanent home. Her Institute of Music flourished for several years until it closed in 1943 after World War II took its toll on enrollment.

Behind her professional fulfillment, Martha had a complicated personal life, with a romantic triangle and attendant drama worthy of an opera. In 1904, just 18, she married Reuben Rich Baker of Wellfleet, the son of the “Banana King,” Capt. Lorenzo Dow Baker, whose first cargo of bananas from Jamaica eventually grew into the United Fruit Company. Seeming to have paused her musical ambitions for domesticity, Martha lived with Reuben in Quincy, where he was president of a yacht company. The marriage was eventually annulled, though the couple had likely been living apart for years while Martha resumed her vocal studies.

By December 1925, Martha, living in Paris, had been named as the co-respondent in a divorce filed by Mary Clayton (Butler) Alberini, the wife of opera singer Alessandro Alberini, a naturalized citizen who had arrived with his family from Italy in 1897.

One story tells of Alessandro being “discovered” by several gentlemen from Boston who heard him singing while working as a farmhand in the potato fields of Ashland, Mass. Recognizing his promise, they arranged for an audition at the New England Conservatory of Music, where, at the same time, both Mary and Martha were studying. A romance blossomed between Alessandro and Mary, and the two were married in 1918.

Yearning to polish his baritone to improve his professional opportunities, Alessandro found a benefactor who helped finance his vocal studies in Milan. He left his wife and baby daughter in Boston and went abroad for two years. It so happened that Martha was in Italy at the same time.

The Barnstable Patriot reported that the “jilted wife,” Mary Alberini, had sued Martha for the “alienation of the affections” of her husband. With the drama making headlines, Martha and Alessandro — who subsequently filed his own countersuit against Mary for cruel and abusive treatment — were married in New York in early 1928.

It seemed that Martha had found a kindred spirit with whom she could share her devotion to music. To a newspaper reporter she declared, “A rare love; the love that understands. To keep up your career and be happily married is possible only when you are married to a very understanding person; and such people are rare. But I have found such a person. And I am sure our happiness will be lasting.”

But every opera has its dramatic twists, and there was one more to come for Martha and Alessandro. In 1935, just seven years after their wedding, Martha sued her husband for cruel and abusive treatment and they were divorced.

In 1938, Martha married the prominent New York financier George R. Baker at the Atwood home in Wellfleet. As an active patron of the arts, Baker (who was no direct relation to the Wellfleet Bakers) joined with Martha in supporting and launching the Institute of Music.

After George Baker’s death in 1944, Martha devoted herself to training young singers at her studios and working with blind musicians. She died in April 1950 at Cape Cod Hospital after a long illness. Burial was reported to be in the Wellfleet cemetery, though there is no headstone marking her grave. Most likely she is buried in the family plot in the town’s Pleasant Hill Cemetery.

Not far from the cemetery along Route 6, motorists drive past a sign for the Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater that announces upcoming broadcasts of the Metropolitan Opera: Live in HD. November’s broadcast of Tosca featured one of Puccini’s best known soprano arias, “Vissi d’arte.” Like Floria Tosca, the celebrated singer of the aria, Wellfleet’s own diva, a sea captain’s daughter, also lived for her art.