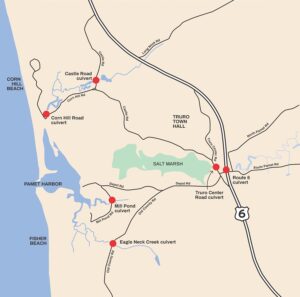

TRURO — The Pamet is not just a tidal river but an entire estuarial system — albeit an altered one — that stretches the width of Truro. At its eastern limit is the barrier beach, and it emerges at Pamet Harbor, where its three branches join and flow into the bay through a tidal inlet. Its branches are mostly unseen as they flow beneath roadways and through undersized culverts that restrict the system’s tidal flow.

The existing culverts pose ecological as well as safety risks, according to experts. The replacement of six of them is the focus of a slow-going restoration project in which the town is working with state and federal employees to install upgrades that will help restore the Pamet’s saltmarsh ecosystem.

The replacement of one of the undersized culverts, at Eagle Neck Creek, was completed in October 2022. Five others are not yet under construction. The effort to restore the Pamet salt marsh has been in the works since at least 2011, according to Dept. of Public Works Director Jarrod Cabral.

A measure passed at the annual town meeting in May authorized the town to fund 25 percent of the replacement of one of the culverts, at Mill Pond. The other 75 percent of the cost will be covered by the USDA, contingent on the 25-percent commitment from the town. Voters will be asked to approve the funding at a June 27 special town election.

Because the culverts restrict tidal flow, areas that would naturally have salty or brackish water are atypically fresh. “When you increase the size of the culvert for tidal flushing, water quality is going to increase over time,” said Cabral.

Together, the state’s Div. of Ecological Restoration (DER), the Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM), and two federal agencies, the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service’s Cape Cod Conservation District and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), have committed $7 million so far to the restoration project. Those funds cover engineering and modeling services for the various culvert upgrades. The town will not be responsible for replacing the culvert under Route 6, which is property of the state Dept. of Transportation.

Cabral said there has been a phragmites buildup throughout the Pamet system. In particular, between two of the culverts that flow into each other — the one under Route 6 and the other under Truro Center Road — there’s been a surge in the invasive species, according to Danielle Perry, the restoration project’s contact at NOAA.

Phragmites, a perennial weed, forms dense masses, clogging marine ecosystems and inhibiting other plant growth, according to Mass Audubon. That in turn cuts back native wildlife habitats and populations. “Being able to add more salt water to the system will help,” Perry said.

In restoring tidal exchange, said Cristina Kennedy, a coastal wetlands restoration specialist with DER, “we’re looking at tide levels upstream and downstream, before and after we restore.” The goal, Kennedy said, is for high and low tides to match upstream and downstream from the culverts. That might not happen perfectly: “You get to maybe 80 or 90 or 95 percent” tide uniformity, “which is good enough to restore the salt marsh ecosystem,” Kennedy said.

Another environmental benefit associated with saltmarsh ecosystems is carbon sequestration: healthy salt marshes take in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in plant material and sediment.

Still Years to Go

The Pamet system’s culvert replacement plans are at varying stages of modeling and development. The restoration project’s overall timeline for permitting and construction isn’t clear yet, but Cabral estimated “maybe 2030 at best” for when replacement at all the sites will be underway.

The modeling aims to determine the appropriate culvert size that would last for five decades. That requires taking in a slew of environmental factors: 100-year storms, record storm surges, and projected sea-level rise over a 50-year span, Cabral said.

At each location, good planning is a matter of finding the project’s sweet spot. Bigger culverts don’t always mean better tidal flow, Kennedy said. Because of tidal hydraulics, if a culvert is too big it can accumulate sand. If it’s too small, as has happened along the Pamet, water can move with such pressure and speed as to cause significant erosion around the culvert.

At Eagle Neck Creek, an eight-by-eight-foot box culvert replaced two 36-inch culverts that had been restricting tidal flow there. The DPW also raised the neighboring road by three feet to further prevent flooding.

At Mill Pond, a similar eight-foot square-shaped culvert is slated to go in where an outdated corrugated pipe is currently in place. A select board majority made that decision in April 2023 after residents objected to a strategy Cabral proposed that would have involved cutting off Mill Pond Road. As the final design is wrapped up, but with a two-year permitting process not yet underway, Cabral anticipates construction of the Mill Pond culvert by 2028.

As for the four culverts that will still need to be replaced — under Corn Hill Road, Castle Road, Truro Center Road, and Route 6 — upgrades are still in the modeling phases. That involves balancing the longevity of a replacement culvert with its cost.

DER advocates “for the most restoration potential, but we understand that there are other important priorities that need to be balanced,” Kennedy said.

While ecology is at the crux of the restoration, there are other risks associated with undersized culverts. Cabral said the upgrades will also “protect town infrastructure, roadways, power lines, utilities, and private property that are in the area.”

“Being able to upgrade culverts allows for more flood control and preventing roads from overtopping,” said Perry.

Tidal flow has been restricted for hundreds of years at the Mill Pond crossing, where a grist mill founded in the 1700s was powered by tidal waters, according to research by Tim Richards, who became a tide mill history enthusiast after buying a house on Mill Pond Road in Truro and delving into historical documents at the Truro Historical Society’s Cobb Archive. Kennedy agreed that the area “has been in a nonnatural state for a really long time.”

With likely a decade to go until the project is completed, there’s still some urgency to the work. “There’s always the risk of a bad storm or hurricane coming through and causing significant damage,” Kennedy said. There are public safety risks and further environmental degradation to contend with along the unrestored Pamet system.

“The sooner the better,” said Kennedy of the project’s timeline.