EASTHAM — On Shurtleff Road, a roughly half-mile residential stretch that curves along Cape Cod Bay in North Eastham, immaculate lawns adorn large new houses. There’s not a pebble out of place in their graveled drives. Amid these testaments to Eastham’s glamor, there are a few holdout cottages — one more notable than the rest.

In the front yard at 295 Shurtleff Road, metallic swine are not the only signs of resistance to these recent developments. A beat-up van with greenery creeping onto its hood is parked in perpetuity on the grass. In its windshield, crooked signs welcome mermaids and advertise the “Viagra Oyster Company.” Next to the propane-tank pigs, welded statues just anthropomorphic enough to be clearly naked greet anyone brave enough to venture close.

“It’s a treasure,” says Sue Beyle, 79, of her front yard. She lives here with Sunny-Girl, a border collie who “has become very protective of me,” Beyle says. “That’s her new job.”

Sunny-Girl’s old job was to guard Noel Beyle, Sue’s late husband, the self-proclaimed “Mayor of West Eastham.” Noel died in 2017 at 76, leaving not only loved ones but also 40 self-published booklets that comically chronicle Eastham’s history and lore.

Tom Ryan, a fellow local historian, had Noel on his radar as soon as the latter arrived in town and cofounded the First Encounter Press, which the Cape Cod Times called “probably Eastham’s first publishing firm,” in 1977. Ryan followed Beyle with more than a passing interest: “I’m an expert on the town,” says Ryan. “He was either a colleague or competition.”

That question may remain unresolved. But as to Noel’s eccentricity, Ryan’s family, who built their house on nearby Western Avenue in 1968, say there are no two ways about it. Mary Ryan, Tom’s sister, remembers Noel as a “fixture in the neighborhood with some odd habits.” Kathleen Lavery, Tom’s and Mary’s sister, adds, “He was a character — and one who didn’t care that much about fashion.”

Noel grew up in Syracuse, N.Y., and after graduating from Syracuse University and earning a master’s degree in political science at the University of Michigan (where he “proved to be quite the singer,” joining the glee club and performing with Perry Como), he dabbled in law, fundraising, and research. His eventual move to Boston was, according to his funeral program, “going in the right direction.”

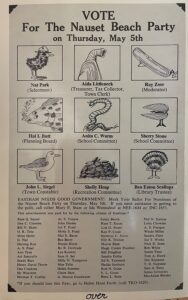

He finally gave in to the pull of Eastham and began churning out his miniature manifestos in 1976, according to a 2019 story in Cape Cod Life magazine. Each is its own carefully curated, two-dimensional iteration of the jaunty clutter in the Beyles’ front yard. A booklet from 1977 endorsed the “Nauset Beach Party” in the town’s upcoming election, with a ticket that included “Hal I. Butt” for planning board and “Bea Eaton Scallops” for library trustee.

A couple of years later, Noel reveled in the social wrongs being rectified by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s announcement that hurricanes would no longer get only women’s names: “Catch your breath all you chauvinist hurricane hunters out there,” he wrote. “The drive for equal rights — and equal wrongs — among the sexes has finally reformed the system for naming Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean hurricanes.”

Other booklets nod to “The League of Non-Resident Non-Voters” and offer recipes for Pat’s Smothered Shark.

Although Noel and Tom Ryan took up similar fields of study — Eastham, past and present — their approaches were about as disparate as the field of historiography allows. “My view of trying to understand local history was very much trying to follow the correct standards in the discipline,” says Ryan, who has done meticulous research about the 1620 “First Encounter” at Nauset. “Mr. Beyle,” he says, “was folkloric and wasn’t bound by normal discipline, protocols, or standards.”

“He was a hysterical historian,” says Sue.

Sue first met Noel’s black Labrador, Kitty-Kitty, while visiting town in the early ’80s. Then she crossed the street, encountered Noel himself, “and the rest was history,” she says.

The two married in Chicago; she was 39 and he was 43 when they moved into the Shurtleff Road home that had belonged to Noel’s parents. The original structure, which still stands, is a two-part assemblage of post-World War II prefabs linked by a hallway. Sue says that when it was built around 1950, it was the tallest house on the block. Noel winterized half of it in the late ’70s, says Sue.

Starting about 10 years ago, she says, the scale of houses on the road increased “like a snowball coming down the hill.”

Art Autorino, chair of the town’s select board, bought a house on Shurtleff Road in 2005 and remembers Noel telling him that when he first moved to town, he could see Route 6 from his window. Autorino is among those who think having big houses along the road has been a good thing for the neighborhood.

“My personal opinion is what’s happened to Shurtleff Road is a benefit, a bonus, because building bigger homes and nicer homes just increases the value of the property,” he says. In 2019, Autorino sold his house and bought a different lot down the street, where he constructed a new one. “I think the value of my home has increased because other people on the street have built bigger homes,” he says.

Tom Ryan’s reflections on the area’s evolution are less sanguine. There’s a “sensation that these mansions are incongruent with the neighborhood,” he says. And not only that, “they separate the small homes — mostly of year-round people who invest their lives here — from the sunset.”

As Shurtleff Road’s houses reach new horizons, Sue’s property remains unchanged. It includes a doghouse out front, marked with a sign reading “Bored of Selectmen.”

She thinks the neighbors mostly want to keep it that way. At least the ones who knew her husband.

“When Noel passed away, my neighbors said, ‘Please don’t take any of that down. It’s going to help us grieve his passing,’ ” says Sue. “We’ll see how long that lasts.”