WELLFLEET — For years, ecologist and beekeeper John Portnoy has sold up to three varieties of honey at the Wellfleet Farmers Market — each made from the nectar of seasonal blooms, first black locust, then winterberry, and last, sweet pepperbush. But on a sunny Wednesday morning this month, his stand displayed only a couple of baskets of garlic and a carton of berries. The honey was missing — as it has been the entire summer.

That’s because Portnoy found thousands of his adult honeybees dead outside their hives this past spring. The culprit behind the apiarian massacre, Portnoy said, was the bacterial disease European foulbrood.

“My bees were so devastated by this disease that they couldn’t bring in a harvestable surplus of honey,” he said. “I was forced to shake all my adult bees into new equipment and burn over 200 combs. That set them way back.”

The disease was likely caused and exacerbated by insecticide poisoning, according to state bee inspector Paul Tessier, who led an examination of Portnoy’s bees. Chemical tests found pyrethrins — chemicals used in insecticides — on the dead bees.

Over the last few years, more homeowners have been calling on pest-control companies to spray their yards with insecticides to kill mosquitoes and ticks. That’s causing concern among farmers about the effects on pollinators and other beneficial insects.

“I have been concerned for a while about the increase in broadcast spraying of pesticides by private companies on properties near our farm,” Portnoy told the Independent.

Statewide, more mosquito and tick companies have been opening, according to Phu Mai, the director of communications for the Mass. Dept. of Agricultural Resources.

“There’s been a big increase in spraying by commercial people,” said Larry Dapsis, the deer tick program coordinator at the Cape Cod Cooperative Extension. “I know their businesses have increased quite a bit. I’ve seen this year in particular heavy-duty marketing from companies like Mosquito Squad, Mosquito Joe, and Mosquito Mary.”

Tony Araujo, owner of the Plymouth franchise of Mosquito Joe, which focuses on the Upper Cape but does some work on the Outer Cape, said that “each year there seem to be more and more” people requesting the company’s services. He said Mosquito Joe’s work involves spraying the perimeters of yards, tall grasses, and other areas that harbor mosquitoes and ticks with a variety of treatments including permethrin and bifenthrin — two synthetic pyrethrins.

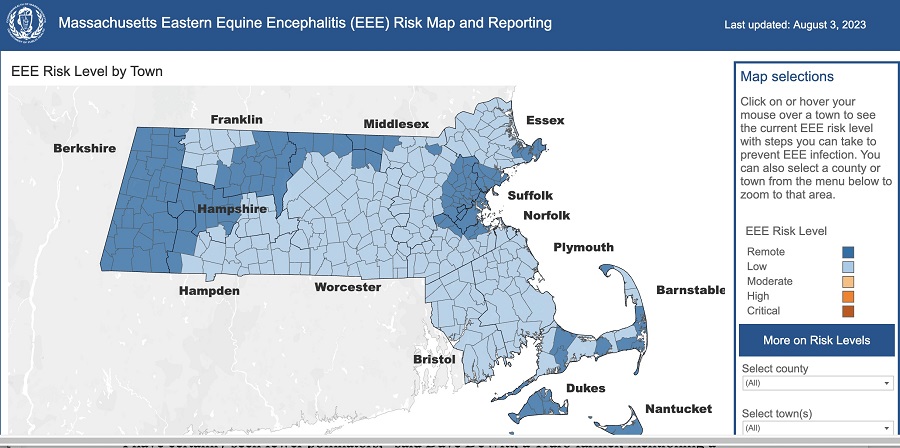

Gabrielle Sakolsky, superintendent of the quasi-governmental Cape Cod Mosquito Control Project, said that she thinks the spike in yard spraying began in 2019 when Massachusetts had “high levels of risk of transmission” of Eastern equine encephalitis, a potentially fatal virus spread by mosquitoes. “It made people very nervous.”

The disease goes through cycles, Sakolsky said; the danger in Barnstable County is currently “low” to “remote” on the state’s risk map.

There was also the overwhelming mosquito presence in 2021 caused by the overwash at Duck Harbor in Wellfleet, which in turn caused a spike in private yard sprayings, as previously reported by the Independent.

But the war against mosquitoes has had unintended casualties.

“Pyrethroids are toxic not just to mosquitoes and ticks; they are highly toxic to most insects,” Portnoy said.

That includes pollinators like bees and butterflies, caterpillars, which are a crucial food source for songbirds, and insects that help to naturally control mosquito and tick populations.

“I have certainly seen fewer pollinators,” said Truro farmer Dave DeWitt, mentioning a particular decline in monarch butterflies. Most of what we eat, including the crops he grows, are reliant on pollinators, he said.

Insecticide applicators have to follow state rules, such as not spraying plants that are in bloom and, depending on the insecticide being used, not spraying on windy days to limit drift.

Dapsis said those regulations effectively protect pollinators if they’re followed, which mosquito control companies said they’re very careful about. “We assiduously avoid flowering plants,” said Curt Felix, a Wellfleet water commissioner and the owner of the Wellfleet franchise of Mosquito Squad, one of the most visible companies on the Outer Cape.

Araujo maintained that Mosquito Joe follows the regulations, and that it’s easy to direct the spray at a specific target and limit drift.

But Mark Faherty, science coordinator at Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, said the regulations are insufficient and do nothing to protect the beneficial insects around flowering plants. He offered a grisly example: caterpillars eat leaves covered in insecticide, begin throwing up green liquid, writhe around, and then die, he said.

Faherty, who is a licensed pesticide applicator, also questioned how closely the regulations are followed, saying he has seen insecticide frequently drift away from where it is sprayed.

“All I’ve seen from day one of these companies is the law being broken,” said DeWitt, who is also a licensed applicator. “I’ve seen nothing but abuses.”

DeWitt said spraying affects nearby bees, which travel up to three miles from their hives. “If you spray someone’s home and a beekeeper is next door, you’re spraying their bees,” he said.

Portnoy said he and other ecologists on the Cape are “concerned that the state pesticide board does not have good control and monitoring of this private-company spraying of adult mosquitoes and ticks.”

Beyond the harm yard spraying does to beneficial insects, there is also doubt about its effectiveness at limiting the mosquito population.

Experts recommend a targeted spray of a yard’s perimeter to combat ticks but say that yard spraying is ineffective against mosquitoes, which can travel up to 10 miles. That means that after a spray kills a yard’s mosquitoes, others will soon arrive.

“Spraying for mosquitoes is the biggest waste of money,” Dapsis said.

Dapsis said he has also heard of some companies spraying entire properties, a pointless exercise given the fact that ticks are located only on the perimeter, not in lawns or close-cropped garden areas. Felix and Araujo each said their companies usually don’t spray lawns but will if the customer requests it.

Dapsis, Sakolsky, and Faherty all questioned the effectiveness of the “natural” treatments that some companies claim to use. For one thing, the term does not necessarily mean a product can’t hurt the environment. Faherty said treatments can be marked “natural” based on the active ingredient, but they can have other components that are unregulated and harmful to insects.

Still, Felix said that while Mosquito Squad sometimes uses permethrin, it mostly sprays foliage using solutions that feature essential oils rather than chemical insecticides.

But research shows “those products just do not work,” Dapsis said.

“Either it doesn’t work, in which case you’re ripping people off, or it kills beneficial insects left and right,” Faherty said.

Sakolsky said a strategy far more effective than yard spraying is searching for areas of standing water where mosquitoes might be breeding. Araujo and Felix said their companies do that as part of their services.

A larger-scale approach, like the one taken by the Cape Cod Mosquito Project, is even more critical, Sakolsky said. That means opening up waterways to limit mosquito breeding and allow mosquito larvae to be accessed and eaten by fish, and sometimes applying larvicide, which has little effect on the environment.

But with homeowners continuing to have individual yards sprayed for mosquitoes, farmers are worried, especially given what happened to Portnoy’s bees.

“He is one of the best beekeepers we have in Barnstable County,” DeWitt said of Portnoy. “To find out his hives are dying because of mosquito spraying is frightening.”