Though there are no hard numbers for the population of Canada geese on the Outer Cape, it’s not hard to infer that they are growing. And there’s little argument about one of their more annoying characteristics: the volume of excrement they produce.

Each adult goose creates a pound of droppings per day on average. That’s a lot of poo. And their droppings can contain E. coli, Salmonella, Cryptosporidium, and other disease-causing microbes.

But contamination and disease are not, it turns out, serious issues according to those who study the environment on the Outer Cape. A bigger problem is what they eat.

Canada geese like to congregate in open areas like meadows, golf courses, cemeteries, and beaches. This can be a source of frustration for humans.

Returning home after a week away, one part-time resident of a house on Long Pond in Wellfleet reported cleaning up nine dustpans full of goose droppings from her dock. She wrote to the Independent worried that she had contracted a rash known as swimmer’s itch from contact with goose poop.

That the droppings would bring about the itch is unlikely.

Swimmer’s itch, or cercarial dermatitis, is a harmless condition caused by a parasite that can be found in goose droppings. The Barnstable County Dept. of Health and Environment receives about one call per year reporting a case of swimmer’s itch contracted in ponds. But Sophia Fox, an aquatic ecologist with the Cape Cod National Seashore, said it is unlikely that swimmer’s itch would result from geese near a pond because the parasite requires snails that are not found here.

There are two distinct populations of Canada geese (Branta canadensis) in North America. One population is migratory. Historically, they were a rare sight in Massachusetts. They breed in the Arctic and sub-Arctic, stopping on Cape Cod in the spring and fall to rest.

Then there is a mostly nonmigratory resident population that has shown tremendous breeding success in North America. Up until the 1930s, waterfowl hunters held geese captive for use as live decoys. After the use of live decoys was outlawed, some of these geese were released into the wild. Having lost their ancestral migratory patterns, they began nesting in the areas where they were released.

With an annual growth rate of nearly 2 percent, the population of resident Canada geese in North America has exploded. Here they find an abundance of habitat. And human intervention dating back to the arrival of European colonists has also played a role. Europeans first paved the way for Canada goose colonization by cutting down forests and opening up land to farming. Open fields are excellent habitat for Canada geese.

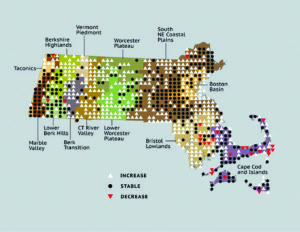

Mass Audubon considers the geese “nearly ubiquitous and strongly increasing,” though in a few locales, their population is actually declining. Between the 1970s and 2000s, Mass Audubon conducted two surveys, called bird breeding atlases, and collected data on Canada geese nesting habits. On the Outer Cape, their population is growing: six areas (called “blocks”) have seen an increase in breeding Canada geese, five blocks have remained stable, and one block has decreased (see map).

Sophia Fox said the effect of goose droppings on pond water quality is minimal. While it is possible that droppings contribute to the nitrogen level in ponds, she said, wastewater and fertilizers are the main contributors to the overall nitrogen load. For the most part, the nutrients in goose droppings simply sink into the sediment, becoming a part of the “benthic detritus food web,” Fox said — benthic meaning at the bottom of the pond.

Far more worrisome is the effect of Canada geese on native plant life surrounding ponds. Stephen Smith, a plant ecologist at the Seashore, said, “We do think that Canada goose grazing has almost eliminated a population of a state-threatened aquatic plant, Orontium aquaticum, or golden club, from the ponds in and around the Province Lands bike path.”

“Ponds are really special and sensitive ecosystems,” noted Fox. The Seashore has set up decoys to scare geese away in some places. One pond in Provincetown’s Beech Forest had a fake alligator head installed. Unfortunately, it didn’t work very well.

Because of rapidly increasing resident Canada goose flocks, the Mass. Div. of Fisheries and Wildlife seeks to control the population by allowing hunters to harvest 30 to 35 percent of the birds annually. Under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, all Canada geese are protected. But hunting resident geese is permitted in September and again from late January to mid- February, avoiding the period when migratory Canada geese are wintering here. According to Drake Larson, a sustainable agriculture researcher at Iowa State University and a hunter, interviewed for a 2011 article in the Atlantic, they are “yummy” and supply his family with “good, lean, rich meat.”

There are ways to keep the resident geese at bay besides hunting. First, do not feed them. They are perfectly capable of finding food on their own. Feeding only encourages them to stay in one place. Second, scare them away with decoys or bright objects. Third, obtain a Fisheries and Wildlife permit (at mass.gov/masswildlife) to addle the eggs by treating them with vegetable oil, a method of destroying the eggs considered by some to be more humane than hunting.